Analysis of China's Export Efficiency and Potential of Digital Products to RCEP Countries-based on the Stochastic Frontier Gravity Model

Wen Zhang1*

1School of Business, Jiangsu Ocean University, Lianyungang, Jiangsu Province, China

*Correspondence to: Wen Zhang, School of Business, Jiangsu Ocean University, Cangwu Road, Lianyungang 222005, Jiangsu Province, China; Email: 15837009022@163.com

DOI: 10.53964/mem.2024013

Abstract

Objective: This paper analyzes the factors affecting China’s digital product exports to Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) countries, and puts forward relevant suggestions on this basis. It is hoped that China’s digital product exports to RCEP countries can be improved, and china’s international competitiveness in the digital field can be enhanced.

Methods: This paper constructs a stochastic frontier gravity model to calculate the export efficiency, and analyzes the relevant factors affecting export efficiency based on the export efficiency model.

Results: China’s overall export efficiency of digital products to RCEP countries is relatively high. China’s digital product trade with RCEP countries is positively affected by the GDP of the two countries, the population size of the RCEP countries, whether the two countries have a common language and whether they are adjacent to each other, and negatively affected by China’s population size and the geographical distance between the two countries. In addition, signing a free trade agreement, improving the level of digital infrastructure, intellectual property rights, tariff freedom, and government spending can effectively improve the efficiency of digital product export trade, while commercial freedom and monetary freedom have a suppressive effect on the efficiency of digital product trade.

Conclusion: China can promote the export of digital products by signing free trade agreements and strengthening investment cooperation in digital infrastructure and intellectual property assistance with RCEP countries. Exporting countries can promote trade cooperation with other countries by moderately reducing tariffs and increasing government investment.

Keywords: RCEP, digital products, export efficiency, export potential

1 INTRODUCTION

China officially signed the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) Agreement with Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand and the ASEAN ten countries on November 15, 2020. RCEP is currently the free trade agreement that covers the largest number of economies, global scale, and development potential. It advocates that partner governments adopt a more open and inclusive attitude towards digital trade and optimize the digital trade environment. As an important part of digital trade cooperation between China and RCEP countries, digital products have strong growth momentum. The total global trade in digital products has more than doubled from US$53.757 billion in 2000 to US$117.06 billion in 2021.Since China joined the WTO in 2001, its advantages in global digital product exports have continued to expand, China is currently the world’s largest exporter of digital products. RCEP countries are important overseas markets for China’s digital product trade. In 2021, China’s digital product exports to RCEP countries accounted for more than 19% of China’s total digital product exports.The official entry into force of RCEP in January 2022 will strongly promote the development of digital product trade in partner countries. As the largest economy in RCEP, China should analyze the efficiency, potential and influencing factors of digital product exports based on the current status of China’s digital product exports. This will be helpful in promoting China’s digital product trade exports and deepening digital trade cooperation with RCEP countries.

The existing literature mainly focuses on the development trend of digital products and the factors affecting the efficiency of digital product trade. Lan Qingxin and Dou Kai (2019) analyzed the evolution of the connotation of digital trade in the United States, Europe and Japan and gave a precise definition of digital trade[1].In terms of development trends, Ivan Shalafanov and Bai Shuqiang (2018) believe that the global Internet penetration and the emergence of new technologies have brought great impetus to the development of digital product trade[2]. Sun Yuqin and Wei Huini (2022) analyzed the scale of digital product trade between China and Central and Eastern European countries and concluded that the scale of bilateral digital product trade has shown a steady growth trend and the growth is significant[3]. Sun Yuqin and Ren Yan (2023) analyzed the scale of digital product trade between China and emerging economies in the Asia-Pacific region and concluded that China’s digital product trade has a booming development momentum and has a certain degree of latecomer advantage and market scale[4].In terms of factors affecting the efficiency of digital product trade, the research of Li Dan and Wu Jie (2022) pointed out that the growth of China’s digital product exports to RCEP partner countries is mainly affected by structural effects and competitiveness effects[5]. Wang Weiwei and Li Yuchen (2023) empirically concluded that China’s Internet development level can promote China’s improvement of digital trade efficiency[6]. Mo Funing and Chen Yaowen (2023) empirically concluded that improving the level of intellectual property protection, Internet development and government spending of RCEP countries are conducive to improving trade efficiency[7]. Zhang Xiying and Liu Min (2023) believe that improving the communication service capabilities of RCEP importing countries and increasing the level of investment openness can promote China’s digital trade exports[8]. Liao Ruofan, Du Qianhui et al. (2024) concluded that the level of economic freedom and political stability will hinder the development of digital trade[9]. Pan Ziyan (2024) concluded that strengthening political mutual trust and economic cooperation between China and RCEP countries will help improve the efficiency of digital trade exports[10].

There is currently no authoritative definition of digital products in academia. The U.S.-Chile Free Trade Agreement signed in 2003 defines digital products as computer programs, texts, videos, images, recordings, or computer programs that are encoded in digital form and can be transmitted electronically. This article refers to the 49 digital products identified under the HS-6 digit code by the United Nations Conference on International Trade and Development (UNCTAD) in 2019, which mainly include five categories: photo and film, printing, music and media, software and video games. This article collects China’s digital product export data to 14 RCEP countries from 2000 to 2021, builds a stochastic frontier gravity model to measure digital product export efficiency, and calculates export potential and expansion space based on export efficiency, and analyzes the factors affecting the export efficiency of digital products based on the model results.

2 CURRENT STATUS

2.1 Export Scale Status

Since China joined the WTO in 2001, the scale of China’s digital product trade exports to RCEP countries has gradually expanded. In terms of export volume, China’s digital product exports to RCEP countries ranged from US$293 million in 2000 to US$466.8 million in 2021. The export volume fluctuated slightly during the period, the overall export volume showed an upward trend. The year-on-year growth rate of exports has an obvious ups and downs trend, but in most years the growth rate is positive and exceeds 10%, the overall growth is relatively significant. In terms of proportion, China’s exports of RCEP digital products accounted for between 10% and 20% of China’s total digital product exports from 2000 to 2021. It can be seen that RCEP countries are the main markets for China’s digital product exports.

2.2 Export Country Status

China’s digital product trade exports to RCEP countries showed a significant upward trend overall from 2000 to 2021. China’s digital product exports to Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, New Zealand and Australia increased by more than 100%, and China’s exports to Myanmar and Malaysia increased by more than 50%. China’s digital product exports to Japan account for the largest proportion among RCEP countries.Although digital product exports to Japan are on an upward trend, the proportion of digital product exports to Japan has dropped from 71.38% in 2000 to 47.4% in 2021, indicating that China has increased its digital product exports to other RCEP countries in recent years, and the scale of digital product exports to other RCEP countries has gradually expanded. Australia and South Korea have a relatively high proportion of China’s digital product exports, accounting for 14.15% and 9.43% respectively in 2021. China’s digital product trade exports to New Zealand, Laos and Brunei account for a relatively small proportion, less than 1%, indicating that the digital product trade markets of these countries are relatively small and have great development potential in the future.China’s export data to RCEP countries are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Current Status of China’s Digital Product Exports to RCEP Countrie

Country |

2000 |

2010 |

2021 |

|||

Exports |

Proportion |

Exports |

Proportion |

Exports |

Proportion |

|

Singapore |

31.91 |

10.87 |

193.04 |

7.44 |

171.08 |

3.67 |

Malaysia |

3.43 |

1.17 |

578.35 |

22.29 |

238.12 |

5.10 |

Indonesia |

5.31 |

1.81 |

41.76 |

1.61 |

141.80 |

3.04 |

Thailand |

5.20 |

1.77 |

27.49 |

1.06 |

119.76 |

2.57 |

Cambodia |

0.12 |

0.04 |

5.38 |

0.21 |

98.02 |

2.10 |

Laos |

0.01 |

0.00 |

5.70 |

0.22 |

5.39 |

0.12 |

Philippines |

18.81 |

6.41 |

26.27 |

1.01 |

91.37 |

1.96 |

Vietnam |

0.42 |

0.14 |

48.60 |

1.87 |

377.64 |

8.09 |

Japan |

209.48 |

71.38 |

1,105.26 |

42.60 |

2,212.68 |

47.40 |

Korea |

11.70 |

3.99 |

266.83 |

10.28 |

439.98 |

9.43 |

Australia |

6.11 |

2.08 |

278.81 |

10.75 |

674.35 |

14.45 |

New Zealand |

0.26 |

0.09 |

11.97 |

0.46 |

43.03 |

0.92 |

Brunei |

0.03 |

0.01 |

0.36 |

0.01 |

0.91 |

0.02 |

Myanmar |

0.68 |

0.23 |

4.76 |

0.18 |

53.66 |

1.15 |

Notes: Due to space limitations, the table only shows data for 2000, 2010 and 2021,the same below. Unit: US$ 100 Million; %.

2.3 Export Structure

This article refers to the UNCTAD and subdivides digital products into five categories: photo and film, printing, music and media, software and video games. There are large differences in the export structure of digital products from China to RCEP countries. video games digital products have always accounted for the highest export share, and the basic share has remained stable at 60%-70% from 2000 to 2021. The second is printing digital products, which basically account for 15%-20%. Then comes software digital products, which basically accounts for about 10%. However, the proportion of music and media, photo and film digital products is relatively small, basically less than 10%, and in most years less than 1%. This indirectly reflects the imbalance in the export structure of digital product trade between China and RCEP countries.The data are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. China’s Digital Exports to RCEP Countries

|

2000 |

2010 |

2021 |

|||

Exports |

Proportion |

Exports |

Proportion |

Exports |

Proportion |

|

Music and Media |

14.10 |

4.80 |

3.06 |

0.12 |

217.09 |

4.65 |

Printing |

241.41 |

20.39 |

546.36 |

12.03 |

190.14 |

22.98 |

Software |

4.72 |

1.61 |

363.70 |

14.02 |

504.67 |

10.81 |

Video Games |

194.97 |

66.43 |

1,380.23 |

53.20 |

2,799.95 |

59.98 |

Photo and Film |

2.97 |

1.01 |

0.18 |

0.01 |

0.32 |

0.01 |

Notes: Unit: US$ 100 million; %.

3 RESEARCH DESIGN

3.1 Theoretical Model

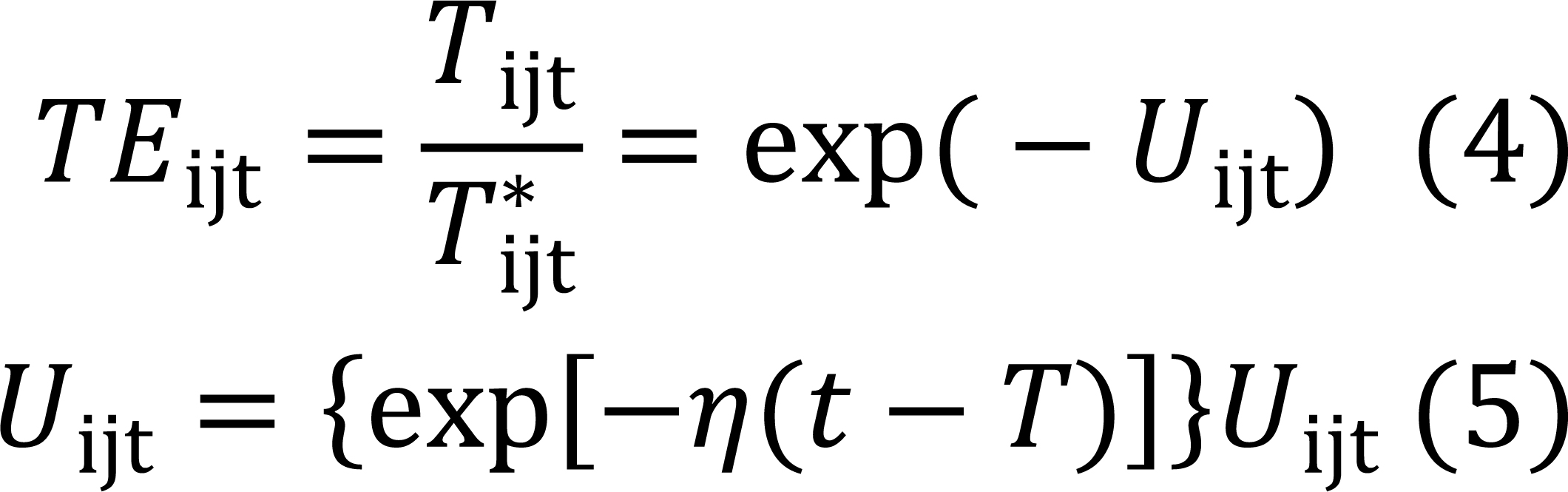

The stochastic frontier analysis method (SFA) was first proposed by Meeusen, Aigner, etc. This method was originally used to explore the technical efficiency problem in the production function.Later, the SFA was combined with the traditional trade gravity model to form the stochastic frontier gravity model, which can not only measure trade efficiency and potential, but also explore the natural and human factors affecting trade based on the results. The stochastic frontier gravity model is expressed as:

|

Take the logarithm of both sides of the formula:

|

In Equation (1), Tijt represents the actual digital trade volume between country i and country j in period t. Xijt is the core explanatory variable of Tijt. Xijt represents the natural determinants of trade volume, such as the distance between the two parties, the scale of their digital economies, and whether there is a common border. βis the parameter to be estimated; Vijt is the random error term, which follows a normal distribution with a mean of 0; Uijt is the digital trade inefficiency term, and Vijt-Uijt is the composite error term. Uijt≥0 means that trade resistance factors exist and have a suppressive effect on trade;When Uijt=0, it means that there is no resistance in trade. Equation (3) represents the optimal digital trade value, that is, the trade potential, between country i and country J if there is no trade resistance within time t.

By dividing the actual trade volume between the two countries by the optimal trade volume, we can get the trade efficiency:

|

In Equation (4), TEijt is trade efficiency, ranging from 0 to 1, and Uijt is the trade inefficiency term. When TEijt=1, it indicates an ideal situation where there is no trade friction between importing and exporting countries. Usually, TEijt takes values between 0 and 1. At this time, there are trade inefficiency factors that create trade friction between importing and exporting countries, and the actual trade volume is less than the optimal trade volume. In addition, according to whether the trade inefficiency term (Uijt) in the model setting changes with time, the stochastic frontier model can be divided into a non-time-varying model and a time-varying model. When the estimated parameter η=0, Uijt=Uij, and the model is a non-time-varying model; when η is greater than or less than 0, Uijt tends to decrease or increase over time, and the model is a time-varying model.

3.2 Stochastic Frontier Gravity Model

This paper establishes a quantitative model for the efficiency and potential of China’s digital product exports to RCEP countries. The specific model settings are as follows:

|

In Equation (6), i, j, and t represent China, RCEP countries, and years, respectively. The explained variable Tijt represents the export volume of digital products from china to country j in year t; the explanatory variables include: (1) GDPit and GDPjt represent the gross domestic product of China and RCEP countries in year t, respectively, This reflects the respective levels of economic development. It is generally believed that the higher the level of economic development, the better the development of digital trade.(2)POPit and POPjt represent the total population of China and RCEP countries in year t, reflecting the market size. (3) DISTij is the geographical distance between China and RCEP countries, reflecting the logistics costs of the two countries.(4) The dummy variables BOR and LANG respectively indicate whether countries i and j are adjacent to each other and whether they have a common language. If they are adjacent to each other and use a common language, the value is 1; otherwise, the value is 0. Vijt is the random error term, and Uijt is the trade inefficiency term, which indicates the distance from the trade frontier level and the trade resistance not explained by the trade gravity equation. Taking into account the heteroscedasticity problem, the model takes the natural logarithm of both sides of the formula.

3.3 Export Efficiency Model

Based on the export efficiency obtained by the Stochastic Frontier Gravity Model, we can analyze the factors affecting export efficiency. The export efficiency model of digital products is set as follows:

|

In Equation (7), i, j, and t represent China, RCEP countries, and years, respectively. TEijt represents the export efficiency of China’s digital product exports to country J. The explanatory variables include: (1)FTAijt represents whether China and RCEP countries have signed a free trade agreement in year t. The year in which a free trade agreement has been signed is assigned a value of 1, otherwise it is 0. The signing of a free trade agreement between the two parties is conducive to promoting the development of digital product trade between the two countries and reducing trade barriers.(2) FBjt is the fixed broadband subscription rate of RCEP country j. It is generally believed that the higher the fixed broadband subscription rate, the better the communication infrastructure level of the country. This article uses this indicator to express the level of digital infrastructure. A good digital infrastructure level will effectively promote trade between the two countries and improve the export efficiency of digital products. (3) PENjt is the number of patent applications from RCEP countries in period t, representing the level of intellectual property protection in digital trade importing countries, thereby reflecting the technological level of digital trade importing countries. (4) BFjt represents the degree of commercial freedom of digital product importing country j in period t, reflecting the degree of freedom in entering and exiting the local market. It is generally believed that the higher the degree of commercial freedom, the easier it is for foreign companies to enter the market and compete with local companies.(5) MFjt represents the currency freedom of country j. It is generally believed that the higher the currency freedom, the more perfect the country’s economic system is and the less regulation it is subject to in trade. (6) TFjt represents the tariff freedom of country j. Lowering tariffs will help reduce trade costs, promote trade and improve export efficiency. (7) GEjt is used to reflect the government expenditure of country j in period t. It is generally believed that the higher the government expenditure, the more it helps to improve the country’s trade environment, optimize related infrastructure to improve the quality of product transactions, and thus promote trade cooperation. This paper takes logarithmic processing of the above continuous variables.

3.4 Descriptive Statistics

This paper selects 14 RCEP countries as research samples, including Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam, Thailand, Japan, South Korea, Singapore, New Zealand, Brunei, Australia, Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar. The time span of the research sample is 2000-2021, and the total number of sample observations is 308. The descriptive statistics of all variables are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics

Name |

Definition |

Expected Sign |

Sample Size |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

Minimum |

Maximum |

lnTij |

Digital product trade export value |

|

308 |

16.93 |

2.64 |

6.07 |

21.61 |

lnGDPit |

China’s GDP |

+ |

308 |

29.32 |

0.88 |

27.82 |

30.51 |

lnGDPjt |

RCEP countries’ GDP |

+ |

308 |

25.74 |

1.95 |

21.27 |

29.47 |

lnDISTij |

Geographic distance |

+ |

308 |

8.16 |

0.56 |

6.86 |

9.31 |

lnPOPit |

Total population of China |

+ |

308 |

21.02 |

0.04 |

20.96 |

21.07 |

lnPOPjt |

Total population of RCEP countries |

+ |

308 |

17.00 |

1.66 |

12.72 |

19.43 |

BOR |

Whether the two countries are bordering each other |

+ |

308 |

0.21 |

0.41 |

0 |

1 |

LANG |

Whether the two countries use a common language |

+ |

308 |

0.14 |

0.35 |

0 |

1 |

FTAijt |

The year in which China and the RCEP countries signed a free trade agreement |

+ |

308 |

0.15 |

0.36 |

0 |

1 |

lnFBjt |

Digital infrastructure level |

+ |

308 |

1.69 |

1.33 |

0.00 |

3.81 |

lnPENjt |

Intellectual property protection level |

+ |

308 |

7.16 |

2.91 |

0.69 |

12.87 |

lnBFjt |

Business freedom |

+ |

308 |

4.19 |

0.35 |

3.04 |

4.62 |

lnMFjt |

Currency freedom |

+ |

308 |

4.35 |

0.17 |

2.69 |

4.56 |

lnTFjt |

Tariff freedom |

+ |

308 |

4.34 |

0.13 |

3.88 |

4.56 |

lnGEjt |

Government spending |

+ |

308 |

4.35 |

0.21 |

3.51 |

4.60 |

4 EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS

4.1 Model Applicability Test

This paper chooses to use the maximum likelihood ratio LR test to ensure the applicability of the Stochastic Frontier Gravity Model and the accuracy of the introduced variables and estimated results, and sets the null hypothesis from four aspects. Test one: whether the trade inefficiency term exists. The null hypothesis is that trade inefficiency does not exist. If there is a trade inefficiency term, the null hypothesis is rejected, and the Stochastic Frontier Gravity Model is considered applicable. Test two: whether the trade inefficiency term changes over time. The null hypothesis is that trade inefficiency does not change over time. Rejecting the null hypothesis means that trade inefficiency is time-varying. Test three: whether to introduce boundary variables (BOR). Test four: whether to introduce language variables (LANG). After the test, the LR statistic is obtained and compared with the P value. The four questions are tested separately using stata 16.0 software. The results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4. LR Test Results

Null Hypothesis |

Constrained Model Log likelihood |

Unconstrained model Log likelihood |

LR Statistic |

Test Results |

Trade inefficiency does not exist |

-370.98 |

-367.05 |

7.85 |

Reject |

Trade inefficiency does not change |

-367.05 |

-352.77 |

28.56 |

Reject |

Does not introduce language variables |

-369.13 |

-358.18 |

21.9 |

Reject |

Does not introduce boundary variables |

-368.45 |

-357.72 |

21.46 |

Reject |

From the test results in Table 4: (1) Trade inefficiency exists. Compared with the traditional OLS regression model, the Stochastic frontier gravity model is more appropriate. (2) The inefficiency term changes over time, indicating that a time-varying model should be used. (3) The hypothesis of not introducing language variables is rejected.(4) The hypothesis of not introducing boundary variables is rejected.

4.2 Estimation Results of Stochastic Frontier Gravity Model

In order to compare the robustness of the model results, this paper also gives the regression results of the time-invariant Stochastic frontier gravity model, the time-varying Stochastic frontier gravity model and the OLS model.

As shown in Table 5, the signs of the core explanatory variable coefficients of the stochastic frontier gravity model of digital product trade in the three models are all in the same direction. In the time-varying model, the coefficient of η is 0.0828, which is significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that the trade inefficiency term decreases at a rate of 0.0828 per year over time, the time-varying model is more reasonable than the time-invariant model. The analysis of the regression results of the time-varying export model is as follows. (1) the estimated coefficients of the GDP of China and RCEP countries are both positive at the 1% significance level, which is consistent with the expected conclusion, indicating the economic development level of the two countries. The higher the value, the stronger the supply and demand for digital products in the markets of the two countries, the greater the promotion effect on the level of digital trade, and the more frequent digital product trade between countries will be. (2) the estimated coefficient of China’s population size is significant and negative at the 1% significance level. This may be because as China’s population expands, the production capacity of the domestic economic market will squeeze out a certain share of trade.The estimated population size parameter of RCEP countries is significantly positive, indicating that an increase in population size will help increase the level of digital product trade in RCEP countries. (3) the coefficients of a common language and whether there is a border are significantly positive, indicating that having a common language and a border between the two sides can help close bilateral trade relations and promote digital product trade cooperation. (4) the distance between the two countries did not pass the significance test and was negative. This may be because in the era of digital economy, the rapid development of the Internet and communication technology is breaking through the geographical boundaries between countries, making the border effect of digital product trade no longer obvious.

Table 5. Model Estimation Results

Variable |

Time-invariant Model |

Time-varying Model |

OLS Model |

lnGDPit |

1.7319*** (0.2953) |

1.5560*** (0.3014) |

1.693*** (0.294) |

lnGDPjt |

1.1974*** (0.1309) |

0.8330*** (0.1109) |

1.245*** (0.121) |

lnDist |

-0.0567 (0.3145) |

-0.2197 (0.1553) |

-0.0458 (0.368) |

lnPOPit |

-21.8943*** (6.8791) |

-27.1603*** (7.0492) |

-21.59*** (6.920) |

lnPOPjt |

0.0352 (0.1379) |

0.0644 (0.9678) |

0.00664 (0.150) |

BOR |

0.8118 (0.1379) |

0.8525*** (0.7260) |

0.921* (0.555) |

LANG |

1.1241** (0.4845) |

1.0493*** (0.2760) |

1.105* (0.566) |

cons |

397.34*** (136.57) |

522.1315*** (141.9302) |

388.8*** (137.4) |

σ2 |

0.9030 (0.1668) |

0.6164 (0.1373) |

0.6816 |

γ |

0.9586*** (0.006) |

0.9556*** (0.001) |

|

η |

|

0.0828 (0.0166) |

|

LOG |

-367.05 |

-352.77 |

|

Notes: (1) Document standard error in brackets; (2) *, ** and *** respectively indicate that t values are significant at 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, the same below.

4.3 Empirical Results of Export Efficiency Model

The export efficiency model is regressed, the empirical results are shown in Table 6.

Table 6. Estimation Results of Export Efficiency Model

Variable |

Coefficient |

FTAijt |

0.0111* (2.33) |

lnFBjt |

-0.00176 (-0.53) |

lnPENjt |

0.00368* (2.22) |

lnBFjt |

-0.0123 (-1.34) |

lnMFjt |

-0.0901*** (-7.39) |

lnTFjt |

0.0344 (1.65) |

lnGEjt |

0.0326 (1.89) |

Cons |

1.068*** (7.77) |

γ*** |

0.9576 (0.0160) |

LOG |

694.33 |

The analysis of the export efficiency model results is as follows:

(1) FTAijt has a significantly positive coefficient, indicating that the signing of a free trade agreement between China and RCEP countries can significantly enhance trade efficiency. the signing of a free trade agreement between China and RCEP countries may be a sign of trade exchanges. Providing a more convenient environment to promote digital product trade will help improve the efficiency of China’s digital product trade exports. (2) The level of digital infrastructure (lnFBjt) is positively related to export efficiency, which is consistent with expectations. It shows that the more complete the RCEP national digital infrastructure is, the more convenient it is for them to conduct digital service trade abroad, and the more likely it is to reduce the transaction costs of digital trade between the two countries, which is conducive to improving the efficiency of China’s digital product trade exports. (3) Intellectual property protection level (lnPENjt) is significantly positive, indicating that improving the domestic intellectual property protection level will help to form a more sound legal system environment, which can effectively protect and support the innovation of digital products, thereby improving the efficiency of digital product exports. (4) Business freedom (lnBFjt) is significantly negative at the 5% level, a higher degree of business freedom will inhibit export efficiency, this is opposite to the expected sign. This may be because higher business freedom means lower costs for entering a country’s market, which in turn leads to more intense competition in the local market, thus inhibiting the export efficiency of digital products. (5) Monetary freedom (lnMFjt) is significantly negative, possibly because most countries in RCEP have similar economic development conditions and monetary policies. (6) Tariff freedom (lnTFjt), government expenditure (GEjt) are positively related to export efficiency, indicating that free capital flow between countries can help improve the export efficiency of digital products. The higher the government spending, the more likely it is that relevant infrastructure will be optimized to provide an efficient and convenient trade environment and improve the quality of trade.Therefore, an increase in government spending in the exporting country will help increase the efficiency of China’s digital product exports to that country.

4.4 Analysis of Digital Product Export Efficiency and Potential

The time-varying stochastic frontier gravity model is used to estimate the export efficiency of digital products from China to RCEP countries from 2000 to 2021. The export efficiency showed a steady upward trend during the observation period, with an average export efficiency of 0.53. The export potential of digital products has increased from US$701 million in 2000 to US$5.656 billion in 2021. Although there are ups and downs, it has shown an overall upward trend. Considering that the export potential is affected by a country’s actual export volume, the expansion space is introduced for further explanation. The article summarizes the regression results of China’s digital product exports to RCEP countries in 2021, as shown in Table 7.

Table 7. China’s Digital Product Export Potential and Expansion Space to RCEP Countries in 2021

Ranking |

Country |

Export Efficiency |

Export Value |

Export Potential |

Expansion Space |

1 |

Japan |

0.93 |

22.13 |

23.67 |

6.97 |

2 |

Australia |

0.93 |

6.74 |

7.22 |

7.11 |

3 |

Singapore |

0.85 |

1.71 |

2.02 |

17.92 |

4 |

Cambodia |

0.84 |

0.98 |

1.17 |

19.06 |

5 |

Philippines |

0.75 |

0.91 |

1.22 |

33.42 |

6 |

Korea |

0.73 |

4.40 |

6.07 |

37.90 |

7 |

Thailand |

0.72 |

1.20 |

1.65 |

38.19 |

8 |

Malaysia |

0.66 |

2.38 |

3.59 |

50.62 |

9 |

New Zealand |

0.66 |

0.43 |

0.65 |

51.46 |

10 |

Indonesia |

0.65 |

1.42 |

2.18 |

54.00 |

11 |

Myanmar |

0.65 |

0.54 |

0.83 |

54.25 |

12 |

Vietnam |

0.62 |

3.78 |

6.12 |

62.16 |

13 |

Brunei |

0.46 |

0.01 |

0.02 |

117.86 |

14 |

Laos |

0.37 |

0.05 |

0.15 |

171.00 |

Notes: Unit: US$ 100 million; %.

Japan, Australia, Singapore, Cambodia and the Philippines have the highest export efficiency, followed by South Korea, Thailand, Malaysia, New Zealand, Indonesia and Myanmar. Among the RCEP countries, Brunei and Laos have the lowest export efficiency. This article divides RCEP partner countries into developed countries and developing countries. From the results, The top three countries in export efficiency are all developed countries. From 2000 to 2021, China’s average export efficiency to developed RCEP countries was 0.63, and the export efficiency of digital products exceeded 0.5 in most years. The average export efficiency to developing RCEP countries was 0.37, and the export efficiency of digital products in most developing RCEP countries remained between 0.1 and 0.5. Overall, china’s digital product export efficiency to developed countries among RCEP countries is at a high level, significantly better than that to developing countries. The possible reason is that digital products, as the foundation of the development of the digital economy, have high requirements for a country’s digital technology and corresponding digital supporting facilities. Developing countries are developing relatively slowly, and the scale of demand for imported digital products is insufficient compared with the former. In addition, the digital trade industry base in developing countries is relatively weak. Out of a desire for protection, developing countries tend to adopt relatively conservative policy measures to suppress the entry of products from other countries, which is not conducive to china’s export efficiency.

The top five countries in terms of export potential are Japan, Australia, Vietnam, South Korea and Malaysia. China’s export potential with Myanmar, New Zealand, Laos and Brunei is relatively small. Countries with high export potential also have high export efficiency levels, reflecting that these countries have high demand for Chinese digital products. China can further deepen international cooperation in the field of digital product trade with these countries. The top five countries in terms of expansion space are Laos (171.00%), Brunei (117.86%), Vietnam (62.16%), Myanmar (54.25), and Indonesia (54.00%). In the future, China should actively carry out digital product trade with these countries, focus on strengthening scientific and technological exchanges and cooperation, jointly cultivate new digital trade models, and promote digital trade cooperation to a new level.

This article further examines the heterogeneous performance under different digital product scenarios. The article summarizes the results of China’s export efficiency and potential of five digital products to 14 RCEP countries in 2021, as shown in Table 8.

Table 8. China’s Export Efficiency of Digital Products by Category to RCEP Countries in 2021

Country |

Photo and Film |

Music and Media |

Software |

Video Games |

|

Singapore |

0.77 |

0.37 |

0.81 |

0.97 |

0.81 |

Malaysia |

0.30 |

0.30 |

0.27 |

0.67 |

0.17 |

Indonesia |

0.40 |

0.20 |

0.25 |

0.70 |

0.08 |

Thailand |

0.51 |

0.25 |

0.82 |

0.64 |

0.14 |

Cambodia |

0.44 |

0.27 |

0.68 |

0.70 |

0.77 |

Laos |

0.52 |

0.08 |

0.73 |

0.88 |

0.23 |

Philippines |

0.73 |

0.25 |

0.39 |

0.55 |

0.47 |

Vietnam |

0.60 |

0.21 |

0.54 |

0.60 |

0.58 |

Japan |

0.87 |

0.41 |

0.80 |

0.87 |

0.77 |

Korea |

0.91 |

0.31 |

0.31 |

0.70 |

0.82 |

Australia |

0.85 |

0.38 |

0.64 |

0.73 |

0.86 |

New Zealand |

0.39 |

0.20 |

0.69 |

0.58 |

0.54 |

Brunei |

0.51 |

0.15 |

0.25 |

0.52 |

0.76 |

Myanmar |

0.40 |

0.17 |

0.55 |

0.47 |

0.81 |

Mean |

0.59 |

0.25 |

0.55 |

0.68 |

0.56 |

Notes: Unit: %.

The digital products with higher average export efficiency are software, photo and film, video games, music and media, with average export efficiency above 0.5, while the export efficiency of printing is relatively low, at 0.25. The reason why the export efficiency of software digital products is the highest may be that the widespread application of digital technology in recent years has promoted the trade cooperation between China and RCEP countries in the software industry.

China’s export efficiency of photo and film to South Korea, Japan and Australia is relatively high, all above 0.8. China’s export efficiency to Malaysia, New Zealand and Myanmar is relatively low, between 0.3 and 0.4.In the printing category, Brunei, Indonesia, and South Korea have the highest export efficiency, but the export efficiency of printing of RCEP countries is lower than 0.5. In the music and media category, Cambodia, Brunei, and Thailand have the highest export efficiency, while South Korea and New Zealand have the lowest export efficiency. In the software category, Cambodia, Japan, and Singapore rank in the top three in export efficiency. In the video games category, Indonesia, Vietnam, Cambodia, and New Zealand have the highest export efficiency, all above 0.8.

As shown in Table 9, video games and printing have the greatest export potential, which may be because the video games industry is still in its infancy in RCEP countries. The export potential of music and media, photo and film, and software is relatively similar.

Table 9. China’s Export Potential of Digital Products by Category to RCEP Countries in 2021

Country |

Photo and Film |

Printing |

Music and Media |

Software |

Vidio Games |

Singapore |

0.06 |

82.79 |

6.20 |

29.22 |

128.61 |

Malaysia |

1.70 |

366.14 |

12.19 |

78.67 |

343.06 |

Indonesia |

0.70 |

290.44 |

0.79 |

77.66 |

220.15 |

Thailand |

0.01 |

210.32 |

1.00 |

61.07 |

172.06 |

Cambodia |

0.02 |

337.44 |

1.09 |

5.31 |

1.31 |

Laos |

0.01 |

40.51 |

1.53 |

0.91 |

1.26 |

Philippines |

0.07 |

164.28 |

0.38 |

42.21 |

52.92 |

Vietnam |

0.05 |

1,234.55 |

2.76 |

89.71 |

91.23 |

Japan |

0.00 |

347.35 |

246.68 |

136.79 |

2,268.67 |

Korea |

0.16 |

222.59 |

20.18 |

116.86 |

333.57 |

Australia |

0.16 |

412.05 |

1.71 |

60.89 |

540.50 |

New Zealand |

0.02 |

66.03 |

0.11 |

6.85 |

44.93 |

Brunei |

0.01 |

4.39 |

0.19 |

0.18 |

0.06 |

Myanmar |

0.01 |

255.64 |

0.07 |

0.20 |

3.08 |

Mean |

0.21 |

288.18 |

21.06 |

50.47 |

300.10 |

Notes: Unit: US$ 100 million.

5 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

5.1 Conclusion

First, China’s overall export volume of digital products to RCEP countries has grown significantly, and the scale of exports has gradually expanded. The export markets to RCEP countries are mainly Japan, Australia and South Korea. There are significant differences in the structure of export products, mostly concentrated in video games and printing digital products. The export structure of digital products is obviously imbalanced.

Second, the GDP of the two countries, the population size of the RCEP countries, and whether the two countries share a common language and border have a significant positive impact on China’s digital product export trade. The size of China’s population and the geographical distance between the two countries have a negative impact on the level of trade in digital products.

Third, the signing of free trade agreements, the level of digital infrastructure, the level of intellectual property rights, tariff freedom, and government spending can effectively improve the efficiency of exporting digital products. Signing free trade agreements with RCEP countries, improving digital infrastructure, improving the level of intellectual property rights and tariff freedoms of RCEP countries, and increasing government spending on RCEP countries can promote the export of digital products. The degree of commercial freedom and currency freedom inhibit the efficiency of digital product exports and will reduce the export of digital products.

Fourth, China’s overall export efficiency of digital products to RCEP countries is relatively high, with an average value of 0.7. Among the categories of digital products, the export efficiency of software, photo and film, video games, music and media are all greater than 0.5. China’s digital product export efficiency and potential to developed countries are higher than those to developing countries.

5.2 Suggestion

First, the Chinese government should strengthen cooperation with RCEP countries in the fields of digital infrastructure and intellectual property protection, China should use its technological advantages to help less developed RCEP countries improve their network levels. For example, China can sign 5G cooperation projects with backward RCEP countries and provide them with technical and financial support as well as intellectual property assistance. it can help improve the legal policies in related fields in the importing countries, thereby optimizing the trade environment in the importing countries and expanding China’s digital product exports.

Second, the Chinese government should continue to promote the signing and entry into force of free trade agreements that include digital product trade clauses, and conduct upgrade negotiations with RCEP countries that have signed free trade agreements with China. Li Bowen and Liu Yisheng(2023) empirically concluded that China’s signing of free trade agreements with Asia-Pacific countries that include digital trade clauses can improve their digital trade efficiency[11]. Combined with the empirical results of this article, it can be seen that China’s signing of free trade agreements with RCEP countries has a positive impact on improving the efficiency of digital product exports, which can reduce trade barriers and further expand the scale of digital product exports.

Third, China should further promote the opening up of the digital sector by setting up relevant management policies to moderately reduce tariffs and increase government investment.In addition, the Chinese government should create convenient and free conditions for the export of digital products. China can promote the export of different types of digital products through targeted measures to optimize the export structure of digital products. For digital products with high technical requirements such as software and video games, the government can increase investment in core scientific research and technology. And the government can increase investment in cultivating professional digital talents to promote the export of digital products such as Printing.

Acknowledgements

Thanks for the support from Education Department of Jiangsu Province and Jiangsu Ocean University.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declared no conflict of interest.

Author Contribution

Zhang W was responsible for designing the study, collecting data, built models for analysis, and made recommendations and improving the content based on the analysis results.

Abbreviation List

RCEP, Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership

SFA, Stochastic frontier analysis method

UNCTAD, United Nations Conference on International Trade and Development

References

[1] Lan Q, Dou K. The evolution of the connotation, development trend and China's strategy of digital trade between the United States, Europe and Japan. Int Trade, 2019; 06: 48-54.[DOI]

[2] Shalafanov I, Bai S. Research on the cooperation mechanism of digital product trade from the perspective of WTO-based on the current development status and barriers of digital trade. Int Trade Iss, 2018; 02: 149-163.[DOI]

[3] Sun Y, Wei H. Thoughts on digital trade between China and Central and Eastern European countries under the background of the “Belt and Road Initiative”. Int Trade, 2022; 01: 76-87.[DOI]

[4] Sun Y, Ren Y. Reflections on digital trade cooperation between my country and emerging economies in the Asia-Pacific region. Int Trade, 2023; 06: 25-35.[DOI]

[5] Li D, Wu J. Deconstruction of dynamic factors of China’s digital exports and research on trade potential-based on the analysis of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement. Asia-Pac Econ, 2022; 03: 46-54.[DOI]

[6] Wang W, Li Y. Estimation of China’s digital trade efficiency and digital trade potential. Stat Decis, 2023; 39: 108-112.[DOI]

[7] Mo F, Chen Y. Research on the export potential of China’s digital service trade to RCEP countries. Contemp Econ Manag, 2024; 46: 63-70.[DOI]

[8] Zhang X, Liu M. Research on the efficiency and potential of China’s digital service trade exports to RCEP member countries-based on the stochastic frontier gravity model. Price Mon, 2023; 12: 78-86.[DOI]

[9] Liao R, Du Q, Huang M. Research on the digital service trade pattern, trade efficiency and potential between China and RCEP member countries-based on the stochastic frontier gravity model. Price Mon, 2024; 01: 44-55.[DOI]

[10] Pan Z. Export efficiency and potential of digital service trade between China and RCEP partner countries-based on the stochastic frontier gravity model. China Circ Econ, 2024; 38: 105-116.[DOI]

[11] Li B, Liu Y. Analysis of the potential and influencing factors of digital trade in the Asia-Pacific region. Asia-Pac Econ, 2023; 03: 65-72.[DOI]

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). This open-access article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Copyright ©

Copyright ©