Viet Nam Overtook the Philippines in 2021: A Microcosm of Asian Development

Josef T. Yap1

1Ateneo de Manila University School of Government, Quezon City, Philippines

*Correspondence to: Josef T. Yap, PhD, Senior Research Fellow, Ateneo School of Government, Ateneo de Manila University, Katipunan Avenue, Quezon City, 1108, Philippines; Email: josef.t.yap@gmail.com

DOI: 10.53964/mem.2024006

Viet Nam surpassed the Philippines in terms of per capita gross domestic product (GDP, in constant 2015 USD) in 2021. This paper analyzes the reasons Viet Nam has overtaken the Philippines despite both countries experiencing challenging transitions in 1986, with Viet Nam significantly lagging behind the Philippines at that time. Qualitative methods are applied through a hermeneutic analysis to understand post-war economic development in Asia. Along with selected quantitative indicators, policy lessons from the history of Asian development are used to analyze and explain how Viet Nam overtook the Philippines. The study shows that many factors can explain the economic surge of Viet Nam between 1986 and 2021: an aggressive outward-oriented strategy, favorable topography that contributed to higher productivity in the agriculture sector, better energy security, and earlier onset of demographic transition. Although the Philippines made important strides in these areas, some experts argue that plans and programs are more effectively implemented in Viet Nam. One reason is the relative lack of accountability in the Philippines, which can be traced to a soft state, weak institutions, a dominant oligarchy, and persistent political dynasties. Meanwhile, revolutionary disruptions after the Second World War may have led to the establishment of a relatively disciplined and inclusive political organization in Viet Nam, the Communist Party. Viet Nam and the Philippines have indeed been an integral part of the remarkable transformation of Asia over the past six decades. Their divergent paths after 1986 may be attributed to factors cited earlier. A cursory survey of the future, however, indicates that institutions in both countries may have to be reformed or transformed to at least achieve the same level of success going forward.

Keywords: accountability, institutions, structural transformation, soft state, oligarchy

1 INTRODUCTION

The year 1986 was a watershed for the Philippines and Viet Nam; following fourteen years of authoritarian rule, the Philippines re-established a democratic government while Viet Nam reformed its central planning system with Đổi Mới [Renovation] in December 1986. At that time, per capita gross domestic product (GDP) of the Philippines was 2.6 times that of Viet Nam (Table 1). Their populations were roughly equal in 1986, although Viet Nam’s was larger by five million. Even though both countries underwent institutional transformations, the Philippines held a significant advantage due to its pre-existing market economy, not to mention that Viet Nam was ravaged by protracted war, beginning in World War II and ending with the cessation of the conflict with the United States in 1975.

Table 1. Comparison of the Philippines and Viet Nam Using Selected Indicators

|

Per Capita GDP (constant 2015 USD) |

Per Capita Gross National Income (GNI) (current USD) |

Population |

Philippines |

|

|

|

1986 |

1,566 |

800* |

56,109,838 |

2021 |

3,328 |

3,550 |

113,880,328 |

Viet Nam |

|

|

|

1986 |

599 |

220* |

61,221,107 |

2021 |

3,409 |

3,590 |

97,468,029 |

Notes: Per capita GNI data for 1986 is actually for 1989 because data for Viet Nam starts only in 1989; per capita GNI in constant prices is available, but data for almost all countries is limited. Source of data: World Bank World Development Indicators. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL

Despite its enormous disadvantages, it has taken Viet Nam only thirty-five years—less than a generation—to catch up with the Philippines. By 2021, Viet Nam had surpassed the Philippines in terms of per capita GDP, and this shift was also evident in the per capita GNI when accounting for overseas remittances. The switch in both indicators took place in 2020, but comparisons would not be valid in that year because of the uneven impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. In this context, the performance of the Philippine economy following the so-called “People Power Revolution” has been markedly disappointing as the country has yet to shed its reputation as “The Sick Man of Asia”.

Viet Nam is the latest addition in a series of debacles. In 1960, the Philippines was ahead of many countries that have since overtaken its economy (Table 2). First was Korea in 1964, followed by Thailand in 1985, with the 1983–1985 economic crisis in the Philippines accelerating the timing of the switch. Indonesia overtook the Philippines in 1993, followed by China in 1998. As shown in Table 3, these rankings have been consolidated over time. The data indicate that over nearly six decades, the standard of living in Korea has improved tenfold than that of the Philippines.

Table 2. Per Capita GDP of Selected Countries, Constant 2015 USD

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1985 |

1995 |

2000 |

2010 |

2020 |

|

Cambodia |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

389.8 |

516.3 |

939.7 |

1,433.4 |

China |

192.4 |

292.7 |

452.8 |

723.3 |

1,653.77 |

2,370.4 |

5,899.9 |

10,567.3 |

Indonesia |

606.8 |

698.8 |

1105.1 |

1,244.3 |

2,021.00 |

1,891.5 |

2,827,3 |

3,855.0 |

Japan |

6,904.7 |

14,675.4 |

19,957.2 |

23,643.3 |

30,831,2 |

31,440.9 |

33,157.3 |

35,309.5 |

Korea |

1,057.0 |

2,124.9 |

4,302.1 |

6,610.5 |

14,270.0 |

17,870.0 |

26,104.4 |

31,914.4 |

Lao PDR |

NA |

NA |

NA |

591.7 |

784.0 |

955.7 |

1,671,4 |

2,556.5 |

Malaysia |

1,338.2 |

1,968.5 |

3,283.5 |

3,532.9 |

6,194.8 |

6,432.9 |

8,402.2 |

10,688.2 |

Myanmar |

145.1 |

157.2 |

205.2 |

225.4 |

243.6 |

354.5 |

984.0 |

1,503.8 |

Philippines |

1,126.7 |

1,392.5 |

1870.0 |

1,579.8 |

1,779.4 |

1,852.4 |

2,489.9 |

3,370.9 |

Singapore |

3,780.5 |

7770.4 |

14,599.4 |

17,844.4 |

31,522.1 |

34,362.9 |

50,382.6 |

62,166.3 |

Thailand |

616.1 |

991.77 |

1,531.7 |

1,830.7 |

3,647.6 |

3,632.3 |

5,200.0 |

6,2077.4 |

Viet Nam |

NA |

NA |

NA |

600.6 |

973.4 |

1,245.9 |

2,131.2 |

3,349.8 |

Notes: Data for 1960 is average of 1960, 1961 and 1962. Same for all years except 2020 which is the average of 2019, 2020 and 2021. Source: World Bank World Development Indicators. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD

Table 3. Per Capita GDP and Exports of Selected Asian Countries, 2021 and 2022

Country |

Per Capita GDP (constant 2015 USD), 2021 |

Per Capita GDP (constant 2015 USD), 2022 |

Export of Goods and Services, 2021 (100,000 USD) |

China |

11,223.1 |

11,560.3 |

3,553,509.0 |

Cambodia |

1,429.9 |

1487.7 |

17,417.5 |

Indonesia |

3,893.0 |

4,073.6 |

255,731.3 |

Japan |

35,507.6 |

36,032.4 |

910,489.0 |

Korea |

32,730.7 |

33,644.6 |

761,244.3 |

Lao PDR |

2,566.3 |

2,599.21 |

NA |

Malaysia |

10,575.9 |

11,372.0 |

256,756.0 |

Myanmar |

1,317.5 |

1,347.5 |

18,415.3 |

Philippines |

3,328.0 |

3,528.0 |

101,446.8 |

Singapore |

67,176.0 |

67,360.0 |

733,772.7 |

Thailand |

6,127.6 |

6,278.2 |

294,505.5 |

Viet Nam |

3,409.0 |

3,655.5 |

341,575.8 |

Notes: Source of data: World Bank World Development Indicators. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.EXP.GNFS.CD

The discussion begins with a historical perspective on development in Asia and is divided into two stages based on key publications. This background allows a comparison of the Philippines and Viet Nam based on the major lessons of development in Asia during the post-war period. The first set of publications includes a 1987 Asian Development Bank (ADB) report[1], alongside publications from the World Bank[2] and a 1997 ADB study[3], all three highlighting Asia’s stellar economic performance before the 1997 financial crisis. The second stage, with Nayyar[4] and another ADB study[5] as headline publications, covers a longer period and considers the sustainability of earlier trends in economic development. Nayyar[4] contains a chapter on Southeast Asia[6], a complete version of which includes a discussion on Viet Nam[7]. An overriding theme in all these studies is an attempt to explain why a similar set of policies worked in some economies and failed in others.

Given the overall success in Asia, it is evident that the collective leadership in the Philippines had opportunities to learn from the success of its neighbors. Either the country’s political, economic, and civic leaders failed to heed the lessons, or even if they recognized them, they were unable to incorporate them effectively into the Philippine development blueprint. Regardless of the actual circumstances, there has been no accountability for these failures in the Philippines. Therefore, any debate or discussion should not only focus on the recipes for success but also on the features of Philippine society that prevent the application of these strategies or constrain their efficacy.

2 METHODOLOGY

Asia, particularly the East Asian region, achieved remarkable development over the past half-century, exceeding most expectations in many aspects—be it economic growth, structural transformation, poverty reduction, or health and education. This can be gleaned from Table 2, particularly for Japan, Korea, and Singapore. “What was primarily an agrarian, rural, low-income region in the 1960s, with most economies struggling to feed their growing populations, has today developed into a global manufacturing powerhouse, with diverse exports, growing innovation capacity, burgeoning cities, and an expanding skilled labor force and middle class”[5].

The next section provides a succinct analysis of the success in the region, beginning with the 1987 ADB study[1], which has largely been overshadowed by the World Bank’s publication on the East Asian Miracle[2]. ADB’s 1997 report[3] was an attempt to redirect the limelight to an Asian source of punditry, but it was overshadowed again, this time by the 1997 East Asian financial crisis.

2.1 First Stage: World Bank, James, Naya and Meier, ADB

East Asia remains the most celebrated success story of the region. The World Bank study analyzed the high-performing East Asian economies (HPAEs) at that time: Japan, Republic of Korea, Taipei, China, Hong Kong, China, Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand. Not only did these economies exhibit higher per capita income growth during the period 1960–1990 than other developing economies, but they also had lower and declining levels of inequality. This is the essence of the miracle.

However, the description as a miracle did not prevent the authors from identifying elements that contributed to the economic structural transformation. Private domestic investment, combined with significant progress in human capital, were the main drivers of growth. The expansion of the more important factors of production can be traced to sound fundamentals: unusually good macroeconomic management, a secure financial system, education policies that supported the spread of labor force skills, agricultural policies that did not burden the rural economy unnecessarily but instead emphasized productivity gains, a population policy that either actively supported family planning or at the very least did not impede family planning choices, maintenance of price distortions within reasonable limits, and openness to foreign ideas and technology.

Meanwhile, the 1987 ADB study emphasized the policy shift in Asia at that time, which was increasingly toward a more open, outward-looking, market or private sector-oriented approach[1]. Adopting and implementing domestic policies consistent with the aforementioned approach was the key to structural transformation. These policies promoted the efficient use of resources and encouraged private sector initiative. Initial conditions did not matter greatly. An outward-looking set of policies involved moving away from import substitution to export orientation. This distinguishing feature of industrialization in Asia involved undoing or counteracting existing protection measures that discriminated against exports (e.g., reimbursing exporters duties on imported inputs, eliminating multiple exchange rates, and correcting overvalued currencies). Added to this list would be the removal or at least minimization of quantitative restrictions on imports, liberalization of financial markets, and noninflationary fiscal-monetary policies.

Such a set of policies also avoided large price distortions commonly seen with government intervention or private monopolies. This follows the neoclassical mantra of “getting prices right”. The World Bank argued that while important, the more crucial aspect should be “getting the fundamentals right”[2].

The World Bank also pointed out that in all the HPAEs, governments also intervened. The study marked a milestone in reviving the state’s importance in economic development. The policy interventions were varied and sometimes worked through multiple channels, including targeted and subsidized credit to selected industries, protection of domestic import substitutes, the establishment and financial support of government banks, public investments in applied research, firm and industry-specific export targets, and wide sharing of information between public and private sectors.

In this context, both fundamentals and interventionist policies were crucial in the East Asian Miracle. However, consistent with the viewpoint of Rodrik and Rosenzweig[8], having the right institutions in place was necessary for the success of interventionist policies. This was especially important in monitoring the impact of policies and abandoning those that did not work.

The authors of the 1987 ADB study acknowledged that the policies under consideration ranged from the open, market-oriented newly industrialized economies (NIEs) and Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN-4) to the more inward-looking dirigiste regimes of South Asia. Moreover, the role of governments in the NIEs—with the possible exception of Hong Kong, China—was much greater than that prescribed in a neoclassical framework. The authors supported a pragmatic position, recognizing that the governments of Japan and the NIEs were involved. However, they also eschewed the extreme position that these governments were the sole architects of success.

With regard to the role of government, the ADB study deals mainly with the issue of picking winners, wherein selected sectors were provided support through, among other measures, access to credit, export subsidies, and duty-free imports of equipment[1]. The authors make a rather strong conclusion that “whereas the ‘pick-the-winner’ approach may be feasible when rather labor-intensive activities—textiles, garments, footwear, processing, light consumer goods—are involved, selective governmental industrial promotion policies can be very costly when applied to capital-intensive or high-technology areas. Labor-intensive industries involve standardized technology that is readily available in the marketplace, and they require relatively low inputs of capital, skills, and technology. In contrast, heavy and technology-intensive industries are more complex and require substantial inputs of highly skilled manpower and large capital investments”[1]. To bolster this argument, the cases of Singapore and the Republic of Korea were cited as examples. However, the Asian experience in the subsequent years greatly weakened support for this position.

On the eve of the 1997 financial crisis, ADB launched a book[3], a follow-up to the 1987 volume and the 1993 World Bank publication. The study’s main theme underscores that well-functioning institutions and markets are preconditions for economic growth, thereby combining the main arguments of the two earlier studies. However, unlike the World Bank and the earlier ADB study, this research also acknowledges the importance of initial income levels alongside policy and the performance of institutions. Meanwhile, in East Asia, governments generally found a balance between private and public actions, an essential part of the development success in the region. This contrasts with the experience in South Asia and other regions that did not have the same level of success. Their governments tried to do too much, “not only providing public goods, but also trying to run bakeries, mines, steel mills, hotels, and banks”[3]. The study identifies policies that supported the rapid economic growth in Asia, much like those of the earlier studies of ADB and the World Bank.

2.2 Second Stage: Nayyar and ADB

The two studies both cover a fifty-year period. Nayyar and his colleagues compiled a volume in honor of Gunnar Myrdal, commemorating the fifty years since the publication of Asian Drama. Meanwhile, the ADB publication looks back at the fifty years of Asian development that coincide with the Bank’s existence. Both studies analyze the reasons behind the rapid development of Asia. They also focus on what Nayyar[9] defines as ten themes in development that almost select themselves: the role of governments, economic openness, agricultural and rural transformations, industrialization, macroeconomics, poverty and inequality, education and health, employment and unemployment, institutions, and nationalisms. However, their differences are far from subtle.

The ADB publication argues that Asia’s postwar economic success owes much to creating better policies and institutions[5]. These policies and institutions helped promote market economies and a robust private sector, which, in turn, led to sustained technological adoption and innovation. In particular, the process benefited from governments’ decisiveness in introducing reforms, in some instances, drastically when needed. In many countries, a well-defined goal for the future accepted by the majority of the population made a difference, especially when implemented by a competent bureaucracy and strong institutions.

Meanwhile, in the introductory chapter, Nayyar[9] states that the Asian experience shows that experts lack a precise understanding of which institutions and in what forms are necessary or, at the very least, useful for development and within which contexts. In the exceptional cases where the contribution of particular institutions is understood, it is not evident how these institutions are built. Two further puzzles emerge from the Asian experience: “Why did some Asian countries perform so well with unorthodox institutions, and why did other Asian countries with very similar institutions not perform well? The puzzle extended beyond institutions to policies. Similar economic reforms did well in some countries and did not perform well in other countries”[9].

Montes[7] attempts to make a generalization about the relevant institutions and policies in seven Southeast Asian countries: Cambodia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Thailand, and Viet Nam. His analysis of the success stories,with important country variations, hinged on (1) the application of standard sectoral interventions, including implementing tools of import-substitution with a transition to export promotion; (2) state-led capital formation through the establishment of state-owned enterprises, investment in key infrastructure, and supply of credit; and (3) mobilization of prominent indigenous business leaders and large conglomerates, primarily through subsidies, tax breaks, and other incentives, to participate in the development process.

In contrast, the orthodox interpretation is that successful states among the seven aforementioned Southeast Asian countries relied more on macroeconomic stability to promote structural change even as they attempted sectoral intervention. However, Montes argues that except for the Philippines, industrial policy regimes in the other six countries have persisted since 1968, although the specific aspects have evolved[7].

A specific example of the difference in approach of Nayyar[4] and ADB[5] is the treatment of economic openness and structural transformation. The ADB publication traces a linear path from import liberalization to export orientation to industrialization. Montes[7] describes a more nuanced approach. He contends that it would be inaccurate to propose that Malaysia and Thailand (even Indonesia, for that matter) began practicing openness in the mid-1980s through the path of import liberalization. Background papers from the World Bank’s publication[2] about Asia’s “miracle economies” do not suggest orthodox openness on the part of Malaysia and Thailand in the 1980s. Economic openness and structural transformation at that time were largely driven by the surge of foreign direct investment (FDI) from Japanese companies seeking low-cost labor following the realignment of the world’s major currencies in the mid-1980s. Success in attracting FDI depended on state policies to provide these investments with a suitable location to profitably operate production activities for export. From the supply side, the choice to break down the production process into components was prompted by Japan’s priorities to protect its growing dominance in global automobile and electronics markets by transferring labor-intensive tasks offshore in the face of an abrupt exchange rate adjustment.

2.3 Summary Framework

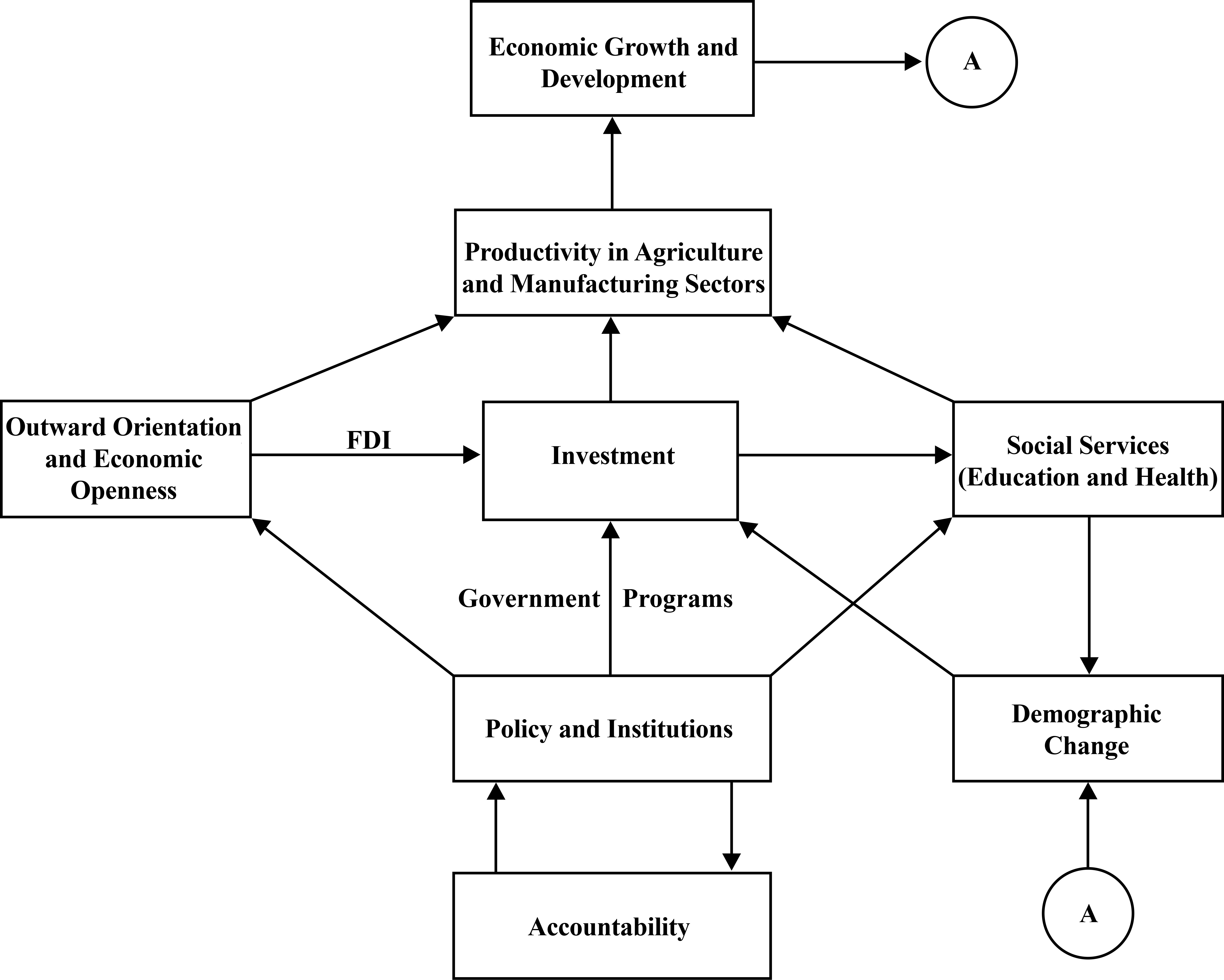

The discussion in Sections 2.1 and 2.2 can be summarized in Figure 1. Major factors in the development of Asia or lack thereof for some countries are highlighted. The analysis ranges from mainstream economics (i.e., neoclassical with an emphasis on price distortions and government overreach) to the more unorthodox (i.e., greater focus on state intervention and institutional underpinnings). Part of the framework anticipates the exposition in Sections 3.6 and 4, specifically the relationship between institutions and a system of accountability.

|

Figure 1. Major factors in economic growth and development in Asia.

As indicated earlier, the primary objective of this paper is to compare the economic performance of the Philippines and Viet Nam. Their experiences can be considered a microcosm of Asian development because both countries applied important elements that proved successful for the NIEs, the HPAEs, and even China. In some cases, the two countries chose diverse policy paths and established different institutions. However, in most other instances, the discussion has to deal with varying outcomes with similar policies and programs. The explanations can differ depending on whether a more orthodox framework is adopted. ADB studies[1,3,5] tend to be more conservative, relying on the aforementioned neoclassical framework. However, as suggested in Figure 1, the system of accountability and its interaction with institutions may be a critical component in the analysis.

3 RESULTS

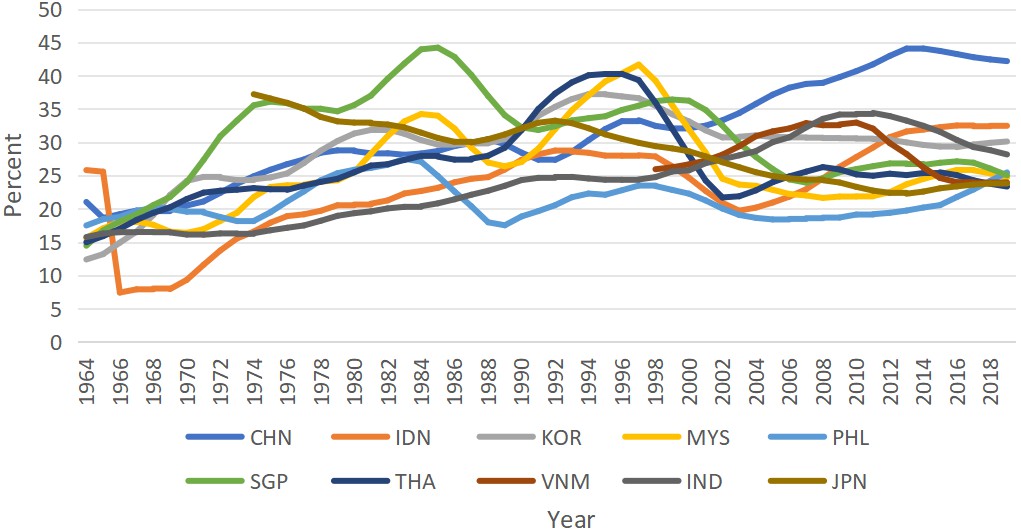

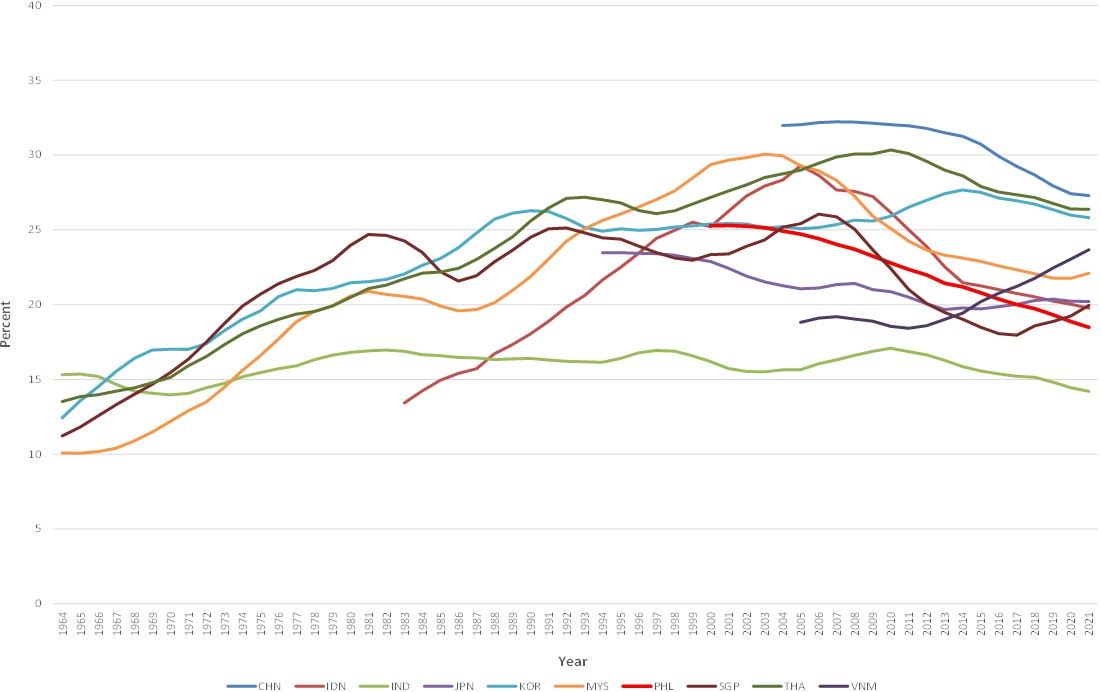

The selection of Figures 2 and 3 to represent key factors of economic development in Asia is justified in Section 2. Figure 2 shows that in terms of the investment GDP ratio, the Philippines has been the laggard among the selected countries. In fact, among the countries listed in Tables 1 and 2, only the Philippines and Cambodia did not reach an investment GDP ratio of 30% in any year from 1960 to 2019. Meanwhile, Figure 3 shows the share of value added from the manufacturing sector in GDP, with a higher ratio representing progress in structural transformation. India’s performance, which is included as a comparator, has been stagnant and below that of the other countries. This confirms India’s relative lack of dynamism because of its overall inward orientation.

|

Figure 2. Investment-GDP ratio for selected countries, 5-year moving average, 1960–2019. Countries are China, Indonesia, Republic of Korea, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Viet Nam, India, Japan. Data is incomplete for some. Available at: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators/Series/NE.GDI.FTOT.ZS

|

Figure 3. Manufacturing-GDP ratio for selected countries, 5-year moving average, 1960–2021. Data is not complete for all countries (China, Indonesia, India, Japan, Republic of Korea, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Viet Nam). Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NV.IND.MANF.ZS

What follows is an attempt at objectively comparing Viet Nam and the Philippines. In particular, Viet Nam could be considered an extension of the East Asian Miracle. In contrast, three decades after the World Bank publication, the Philippines has fallen further down the Asian totem pole.

3.1 Agriculture

Montes[7] explains the Vietnamese state’s comprehensive intervention in agricultural production not only through subsidies and agricultural extension but also through quotas on staple production. Meanwhile, Dy[10] and Adriano[11] provide succinct comparisons of the Philippines and Viet Nam, both highlighting the importance of the agriculture sector. Dy mentions that irrigated land is almost four times bigger in Viet Nam. This is partly explained by the Mekong River delta, which contributes to the irrigation of large areas of low elevation. Similarly, Adriano considers the priority given to the agriculture sector as one of three major factors that facilitated Viet Nam’s rise. In 2020, its budget for agriculture was 6.3% of the total compared to the 1.6% share in the Philippines.

However, Viet Nam’s favorable agricultural experience cannot be understood as only the outcome of reliance on topography and market incentives. In the 1990s, in an application of industrial policy in agriculture, Viet Nam sharply increased investment in rice production, taking advantage of the Green Revolution’s technology-led and state policy-responsive nature, with state support for irrigation, fertilizer, pesticide, and research, becoming a leading global rice supplier[7]. Another important example of a positive outcome is the coffee industry. More than seventeen years ago, Viet Nam’s coffee industry was practically unknown. Currently, the country is the second biggest coffee exporter in the world, behind only Brazil.

In 2021, the agriculture sector in the Philippines contributed 9.6% of GDP and employed 23% of the labor force; the figures are 14% and 38%, respectively, for Viet Nam in 2020. Relatedly, Dy[10] highlights the large discrepancy between agriculture exports: USD 24.55 billion for Viet Nam and USD 4.96 billion for the Philippines using 2016 data. Some may argue that Viet Nam’s better performance is primarily due to its more favorable topography. However, economies like Taipei,China, Japan, and Korea managed to overcome similar constraints confronting the Philippines. While numerous programs have been designed and implemented to boost the agriculture sector in the Philippines, the overall productivity remains low.

3.2 Outward Orientation and Structural Transformation

The success story of Viet Nam’s rice and coffee industries reflects the country’s commitment to an outward-oriented strategy, an area where it significantly diverges from the Philippines. Viet Nam’s decision to join the Trans-Pacific Partnership which eventually evolved into the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) is the most apparent evidence yet of its aggressive stance. In contrast, the Philippines decided not to participate in the TPP negotiations. Even the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership which is not as stringent as the CPTPP did not receive immediate approval from the Philippine Senate.

Table 4 shows that in 1986, Viet Nam’s exports of goods and services were only a fourth of the corresponding value for the Philippines. However, by 2021, Viet Nam’s exports had exceeded those of the Philippines by more than three times, reaching USD 341 billion. The surge in exports was fueled mainly by the inflow of FDI. Between 1990 and 2021, the stock of FDI in Viet Nam jumped from a mere USD 243 million to USD 193 billion. The Philippines has had its fair share of FDI but has a relatively tepid export record compared to its Asian neighbors (Table 3). China is included in Table 4 to underscore the relationship between exports and FDI. The inward stock of FDI amounting to slightly more than USD 2 trillion has translated to USD 3.5 trillion in exports.

Table 4. Comparing Outward Orientation: China, the Philippines and Viet Nam, 1986–2021

|

Exports of Goods, Services (current 100,000 USD) |

Stock of Inward FDI (current million USD)* |

China |

|

|

1986 |

26,223.8 |

20,690.6 |

2021 |

3,553,509.0 |

2,064,018 |

Philippines |

|

|

1986 |

6,310.1 |

3,267.9 |

2021 |

101,446.8 |

113,711.2 |

Viet Nam |

|

|

1986 |

1,744.1 |

242.9 |

2021 |

341,575.8 |

192,571.3 |

*Notes: FDI data are for 1990 and 2021. Source of data: World Bank World Development Indicators; UNCTAD World Investment Report. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.EXP.GNFS.CD; UNCTAD World Investment Report Available at: https://unctad.org/topic/investment/world-investment-report

The combination of FDI and export-orientation allowed Viet Nam to participate extensively in regional production networks (RPNs). Arguably, regional economic integration in East Asia was primarily driven by RPNs[12]. The domestic manufacturing sector was the primary beneficiary of the expansion of RPNs. With a modest start in the electronics and clothing industries, multinational production networks gradually evolved and spread into many industries, such as sports footwear, automobiles, televisions, and radio receivers, sewing machines, office equipment, power and machine tools, cameras and watches, and printing and publishing[13]. The economic transformation allowed the manufacturing sector in Viet Nam to absorb excess labor from the agriculture sector, leading to a sharp decline in poverty incidence. More recent studies show that Southeast Asia benefited a great deal from RPNs[14] and that RPNs in East Asia flourished even after the 2008 Global Financial and Economic Crisis, a period described as the slow trade era[15].

While the trade and FDI data seem to indicate that Viet Nam was able to latch on to RPNs more effectively than the Philippines, the situation is not unambiguous. Data presented in Figure 2. 17 of the 2022 Asian Economic Integration Report[16] show that the measure of regional value chain participation of Viet Nam is somewhere in the middle when compared with 26 Asia-Pacific economies, ahead of Japan, China, and Thailand but below Malaysia and Indonesia. It is even one rank lower than the Philippines, which is part of a multi-faceted enigma. Other data show that: (1) the Philippines has a relatively high share of manufactured exports; (2) its share of medium to high technology exports is also among the highest in Asia; and (3) as stated earlier, it also does fairly well based on a measure showing the degree of participation in RPNs[17].

Even with a fairly high RPN participation rate, the export structure of the Philippines remains shallow, as evidenced by a relatively low ratio of manufacturing value added to GDP (Figure 3). Based on the limited data, Viet Nam has been on an upward trajectory since 2011 and surpassed the Philippines which has been on a downward trajectory since 2000 in 2016. This reflects a dichotomy between the Philippines’ export and domestic manufacturing sectors. The stagnant manufacturing sector can be attributed to the low level of engagement in global value chains or RPNs in terms of volume, as indicated by the relatively low level of FDI inflows into the Philippines (Table 4) and the low level of exports (Table 3). Thus, even though the Philippine export sector is advanced in structure, there is a discernible demotion in depth and breadth compared with the other major Southeast Asian economies, including Viet Nam.

This analysis begs the question of why Viet Nam was able to latch on to RPNs more effectively than the Philippines when both countries were in flux in the mid-1980s when the surge in FDI from Japan began. The explanation can be traced to the economic and political crises in the Philippines from 1983 to 1989, which discouraged Japanese investment from entering the country[17]. Japanese outward FDI reached a peak in 1989 but recorded a secondary peak in 1995. By then, China and Viet Nam were more attractive destinations than the Philippines. Apart from having higher wages than these two countries, the Philippines was reeling from a shortage in electricity supply triggered by the decision to mothball the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant a decade earlier. Over time, Viet Nam’s greater outward orientation allowed the country to integrate more effectively with RPNs.

3.3 Economic Reform and Openness

Attributing the relative success of Viet Nam in attracting FDI to the misfortunes of the Philippines shifts attention away from the pitfalls of orthodox prescriptions. Montes[7] points out that the Philippines pursued a different path toward an internationally competitive industrial sector. While the other six countries were restructuring their economies through state intervention in the mid-1980s, the Philippines embarked on an ambitious trade and import liberalization program starting in 1984, establishing a new path anchored on the long-running domestic debate on eliminating the disincentives created by protection measures. In a series of structural adjustment programs under the direction of the Bretton Woods institutions, the program progressively reduced quantitative restrictions and tariff rates, seeking to encourage private sector involvement.

The subsequent Philippine experience aligns with the concern raised by Nayyar[9]. Historical performance suggests that “countries in Asia that modified, adapted, and contextualized their reform agenda at the same time calibrating the sequence of, and the speed at which, economic reforms were introduced did well in terms of outcomes. In sharp contrast, countries that introduced economic reforms without modification, adaptation, or contextualization and did not pay attention to speed or sequence often ran into problems. This was also the reason why strategy-based reform with a long-term view of development objectives, emerging from experience or learning within countries rooted in social formations and political processes, did sustain and succeed. But crisis-driven reform, often initiated following an external shock or internal convulsion or imposed by conditionality of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, was always more difficult to sustain and less likely to succeed because its preordained template was neither contextualized nor sequenced”[9]. Đổi Mới can be considered to be a strategy-based reform in contrast to the crisis-driven structural adjustment program of the Philippines that started in 1984.

A double-whammy was therefore inflicted on the Philippine economy in the mid-1980s. Not only did it miss out on the rising tide created by Japanese FDI, the structural adjustment program exacted a heavy penalty on the economy. The fixation on repaying external debt[17] exacerbated the situation, contributing to the conditions that caused the country to miss out on the second wave of Japanese FDI in the mid-1990s.

3.4 Investment and Infrastructure

Across the seven countries considered by Montes[7], the rapid transition to industry and manufacturing was facilitated by high national investment rates. The performance of some of these countries is shown in Figure 2. Except for Myanmar, a socialist state, private investment rates played a key role. However, what distinguishes the successful economies is the sizable role of government investment. The Philippines and Viet Nam are taken as contrasting examples in Table 5.

Table 5. Investment Rates for the Philippines and Viet Nam (% of GDP)

|

Total Investment |

Government Investment |

||||

|

1970-1996 |

1997-2015 |

2016–2019 |

1970–1996 |

1997-2015 |

2016-2019 |

Philippines |

17.60 |

18.84 |

26.3 |

2.54 |

2.55 |

4.11 |

Viet Nam |

8.38 |

20.61 |

23.9 |

1.97 |

6.25 |

NA |

Notes: Philippine General Government Construction for 2000-2015 is 3% of GDP. Sources: Data for 1970-2015 from Table 3 of Montes[7]. Total investment data 2016-2019 from World Bank World Development Indicators. Available at: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators/Series/NE.GDI.FTOT.ZS; Government investment data for the Philippines 2016-2019 are figures for General Government Construction obtained from National Income Accounts, Philippine Statistical Authority.

The relatively poor investment record of the Philippines and Cambodia was described earlier. This is consistent with the data for 1997-2015, where Viet Nam outperformed the Philippines, particularly in government investment. A cause for concern for the Philippines is that despite the rallying cry of the administration of President Duterte to “Build, Build, Build,” government investment only rose to 4.1% of GDP in 2016-2019. Total investment, however, increased significantly to 26.3%, and the country can only hope this trend will continue during the post-pandemic period.

The discrepancy in investment rates between the two countries has been manifested in one important area. In 2021, per capita electricity consumption was 1,450.55 kilowatt-hours (kWh) in Viet Nam and only 717.16kWh in the Philippines. Achieving energy security is one area where the Philippines has struggled, and, like the agriculture sector, there is no dearth of plans and programs designed to address this issue. Implementation of these plans is, of course, another matter.

3.5 Demographic Transition

Another critical difference between the two countries relates to a persistent weak link in the Philippine development experience. The average population growth rate in the Philippines between 1986 and 2021 was 2.04% compared with Viet Nam’s 1.34%. This indicates that the Philippines had difficulty bringing the rate below the 2% threshold necessary for a successful demographic transition. A fairly young and large population results in a high dependency ratio that reduces resources for investment purposes. This explains the arrow linking demographic change to investment in Figure 1. Nevertheless, the annual population growth rate in the Philippines has fallen below two percent since 2005. In 2021, the figure was 1.5%. But this pales in comparison to Viet Nam’s record, where the annual growth rate fell below 2% in 1993 and further to 0.85% in 2021. Undoubtedly, Viet Nam’s demographic structure is partly in response to its rapid development, and lately, there has been concern about its aging population. It remains to be seen if current population trends in the Philippines will lead to faster economic growth.

3.6 Institutions, Collective Action, and Accountability

A logical starting point for a discussion on institutions is the concept of a “soft state”, which figures prominently in Myrdal’s analysis and is covered by Nayyar[4]. In a soft state, governments are not willing or able to do what is necessary to attain development objectives because they can neither withstand nor compel powerful vested interests[9]. In the view of the international community, if a society is saddled with a soft state vulnerable to elite capture, it might as well let market forces discipline both the state and the private sector[7]. The concept of the soft state had to be refined to account for the multifarious country experiences, particularly those of the NIEs, India, and China. This gave rise to the concept of a developmental state, which highlights the role of public bureaucracies[18]. For purposes of discussion in this paper, the notion of a soft state as defined by Myrdal is retained.

Earlier, it was argued that even if the recipes for development are known, the collective leadership in the Philippines has either failed to apply the strategies or failed to use them effectively. An oft-cited factor for the inadequate economic progress in the Philippines is the lack of collective action, which can be traced to weak institutions or what is essentially a soft state[22]. In the aftermath of the 1986 upheaval, an opportunity arose to address this flaw in Philippine society. However, there was an imbalance in the reform agenda that led to a bias toward economic reforms and not enough effort toward the implementation of political reforms. Among the latter are aspects related to good governance, such as political party reform, freedom of information, and dynasty regulation, all of which could have helped shift political power away from the monopoly of political clans[20].

This author has argued that weak institutions and an oligarchic private sector combined with political dynasties are two sides of the same coin[17]. A gridlock has evolved wherein stronger institutions are necessary to loosen the grip of the oligarchs and political dynasties. At the same time, the influence of oligarchs and political dynasties must be reduced to strengthen institutions.

An important consequence of this gridlock is a political vacuum that fosters a lack of accountability. The latter aspect was highlighted by Adriano[11], who describes the Vietnamese style of economic management as “corporatist”. Targets are set across various sectors, whether in government departments, state-operated enterprises, or local government units. Failure to meet these targets will lead to the replacement, transfer, or disqualification of the respective heads and others who are answerable. This aligns squarely with the role of the Communist Party described earlier.

Meanwhile, Adriano[11] considers as flawed the assumption that under Philippine-style democracy, incompetent officials will be held accountable by being voted out of office by the electorate. A likely reason for this is the problem of responsibility attribution. Low clarity of responsibility and the issue of attribution often weaken the effectiveness of democratic accountability[23]. This, in turn, is caused by the absence of a strong and stable party system in the Philippines, reflecting an electoral system that is predominantly patronage and personality-based[24]. Without prominent and stable political parties, there are no distinct platforms for the electorate to choose from. There is also no mechanism to discipline potential candidates. The failure of specific policies and programs cannot be attributed to a particular group because parties become indistinguishable from one another. This author has argued that this lack of accountability has allowed many personalities and families to retain political power despite the stagnation in the living standards of many Filipinos. The result has been the proliferation of political dynasties.

The lack of accountability in the Philippines is exemplified by two aspects. One is the failure to recover ill-gotten wealth from prominent cronies of the Marcos Sr. regime. The inability to hold them accountable is clear evidence of a political system that was unable to reject the culture of corruption and cronyism[20]. The second aspect relates to the numerous unsuccessful attempts to strengthen and institutionalize the party system in the Philippines. The main reason is that the reform process in the legislature is ultimately derailed by politics[24]. All things considered, the quality of political and social institutions in the Philippines has been adversely affected by the colonial experience, the emergence of oligarchs and cronies, and the stranglehold of political dynasties.

4 DISCUSSION

Given its head start, however, the inability of the Philippines to sustain its advantage over Viet Nam is somewhat difficult to explain. Moreover, by the early 2000s, the Philippines had recovered from the crisis in the 1980s, at least in terms of per capita GDP (Table 2). In particular, Philippine policymakers have generally been aware of the recipes for success. Bulaong O, Mendoza G and Mendoza R enumerate a number of significant economic reforms since 1986, among them the New Central Bank Act (1993), the Competition Law (2015), and the Reproductive Health Act (2012). Other items that can be included are the establishment of the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (1995) and the shift to the “K to 12” program (2012) for basic education. More recently, Republic Act 11659, amending the Public Service Act, was signed into law on 21 March 2022 to attract more FDI and improve the quality of services. The Public Service Act defines and limits the scope of public utilities and simultaneously eliminates the 40% limit on foreign ownership in sectors not considered public utilities. This allows for full foreign ownership of telecommunications, airports, airlines, shipping, and other services.

A Vietnamese friend of this author encapsulated the fundamental difference between policymakers of the Philippines and Viet Nam. Filipinos are excellent planners, implying they have a comparative advantage in conceptualizing and designing plans and programs. Many of these plans and programs have been adopted by its Asian neighbors, including Viet Nam. However, Vietnamese policymakers have been more successful in implementing these plans. Explaining the inability to generate sustainable growth in the Philippines, therefore, has to reckon with factors beyond economic policy. This echoes the analysis in Section 3.6, which deals with the culture of accountability.

A program of reform can address the accountability gap that may exist in Philippine governance[25]. However, a more comprehensive analysis of development constraints should consider a multi-disciplinary approach that can put more emphasis on the “deep parameters” affecting economic performance. For example, related to the institutional dimension, culture, and values can partly explain the lack of social cohesion, spotty entrepreneurship, and general inability to establish a credible and selfless political leadership in the Philippines. In this regard, a political economy framework and a variant of the new institutional economics can be adopted. This relates to the debate between adopting an incrementalist or radical reform process in order to redistribute power to the appropriate groups in society[21]. Earlier, it was implied that Viet Nam and China had undergone a radical reform process.

For the Philippines, Nye[26] outlines a framework for including institutions in restructuring society that hews closely to the incrementalist approach. He argues that the oligarchy will support reforms only if a critical subset of the coalitions that form the oligarchy will see that the changes are in their best interests. “Ideally, reforms are started where resistance is weakest and where changes become self-sustaining and hard to resist once under way”[26]. Relatedly, Fabella[22] posits that engaging the oligarchy constructively implies that the Philippine government must limit its role to activities with well-defined capabilities, such as regulation, enforcing contracts, and protecting private property. “Moving away from owning and operating businesses towards regulation and the safeguard of competition is the preferred pathway in weak institutions environment”[22]. At the same time, economic activities of the oligarchy or more specifically conglomerates should be nudged towards the tradable goods sector, such as food production, or towards the component of the non-traded goods that highly complements the traded goods sector, e.g., energy security. Fabella[22] recommends that local firms and conglomerates enter the slipstream of large global players in the traded goods sectors, a strategy he labels “slipstream industrialization”. In practice, this is participation in RPNs.

The key issue remains the establishment of a greater sense of accountability. Government institutions can be strengthened by focusing on their core competencies, enabling them to enforce accountability[25] (e.g., the Philippine Competition Commission advancing to a stage where it fosters a truly level playing field). Meanwhile, a properly incentivized oligarchy will invest in sectors that spur positive feedback loops, leading to faster economic growth. But as implied earlier, credible and selfless political leadership remains a sine qua non to building effective institutions and consolidating a system of accountability. As aptly observed by Bulaong et al.[20]: “Arguably, with certain exceptions, the Philippines has not had a genuine statesman or stateswoman in the classical Greek sense: a politician who, among other characteristics, governs for the public good”.

5 CONCLUSION

Viet Nam and the Philippines have both been an integral part of the remarkable transformation of Asia over the past six decades, reflected in its demographic transition, social progress, and economic development. Since 1986, the two countries have had divergent paths, with Viet Nam emerging from the ravages of a protracted war to overtake the Philippines in 2021. Earlier sections provided an explanation of this phenomenon, largely based on factors that have driven Asia’s development. In this section, a cursory survey of the future is undertaken in order to identify the major challenges facing Asia in general and Viet Nam and the Philippines in particular. Policies and institutions that may have generated success in the past may need to be reformed or even transformed to sustain the achievements.

Predictions about the future of Asia range from the sanguine[27] to the pessimistic[28]. On the one hand, the macroeconomic conditions of the continent remain buoyant. There is a large population that is a steady source of labor, a growing middle class that sustains aggregate demand, improving social infrastructure for education and healthcare, and expanding physical infrastructure. Nayyar[27] cites long-term projections by OECD of GDP in constant 2010 Public—Private—Partnership US dollars for major countries, which show that the share of Asia (excluding Japan) in world GDP will be 50% in 2030, 53% in 2040, and 55% in 2050. This suggests that the share of Asia (excluding Japan) in world GDP in 2050 will return to its level in 1820 when it was 56%.

On the other hand, the period after 2019 has been quite challenging for Asia, underscoring the diversity in the region. Asia was hard hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, and economic recovery has been patchy, particularly for China. This was exacerbated by China’s escalating political and trade tensions with the US and some of its neighbors. These conflicts have served the interests of the anti-globalists, who had been critical of the inequalities that were spawned by the hollowing out of manufacturing in many industrialized countries and the rising trend toward urbanization. Anti-globalization populism threatens the regime of open trade and investment, one of the key drivers of Asian economic growth. At great risk would be the RPNs or, more broadly, global value chains. They may be adversely affected by a re-shoring or relocation of production in the United States or Western Europe. The structure of RPNs and trade in general will also be affected by technological changes, especially those associated with the Fourth Industrial Revolution, referring to advanced robotics, artificial intelligence, 3D printing, and the Internet of Things. The new technology could have far-reaching implications for the location of production, manufacturing-led development, the future of manufacturing, employment possibilities, especially for low-skilled labor, and the future of work[27].

In the medium term, East Asia faces a daunting demographic dilemma where fertility has plummeted below replacement rates, populations are aging, workforces are declining, and in Japan and China, the population has begun falling. Being home to the two most populous countries, Asia is also at the center of the climate movement. Any significant action to reduce global warming has to have the support and cooperation of Asian countries.

This study does not propose policies and programs to deal with these challenges. Instead, what is emphasized is that institutions and accountability will matter significantly when addressing these issues. Moreover, success in the past is not a guarantee of similar outcomes in the future. Nayar[27] argues that the growing political consciousness among people as citizens, together with their aspirations for better lives empowered by digital technologies and demonstration effects, will make governments more accountable over time. In the case of Viet Nam and, perhaps, China, it has to consider following the path of some of the NIEs and HPAEs towards greater democratization. For example, it has been empirically determined that business firms in Viet Nam have heterogeneous views about economic constraints, and these often differ from the perspective of the national government[29]. In the case of the Philippines, while the country has a very vibrant civil society, as discussed in Sections 3.6 and 4, the mechanisms to translate good concepts into concrete action remain inadequate.

Acknowledgements

The author wanted to express his gratitude to Manuel F. Montes, Senior Advisor, Society for International Development, and two anonymous referees for their comments and suggestions. The excellent research assistance of Joyce Marie P. Lagac was also acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declared no conflict of interest.

Author Contribution

Yap JT was responsible for writing the original draft, and reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Abbreviation List

ADB, Asian Development Bank

ASEAN-4, Association of Southeast Asian Nations

CPTPP, Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership

FDI, Foreign Direct Investment

GDP, Gross Domestic Product

GNI, Gross National Income

HPAEs, High-Performing Asian Economy

NIEs, Newly Industrialized Economy

RPNs, Regional Production Networks

References

[1] James W, Naya S, Meier G. Asian Development: Economic Success and Policy Lessons. University of Wisconsin Press: Wisconsin, US, 1987.

[2] World Bank. The East Asian Miracle: Economic Growth and Public Policy. Oxford University Press: New York, US, 1993.

[3] Sarkar A. Emerging Asia: Changes and Challenges. Asian Development Bank. 1997. JAS, 1998; 57: 795-796.[DOI]

[4] Nayyar D. Asian Transformations: An Inquiry into the Development of Nations. Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019.

[5] Asian Development Bank. Asia’s Journey to Prosperity: Policy, Market, and Technology Over 50 Years. Asian Development Bank Publishing: Mandaluyong, Philippines, 2020.

[6] Montes M. Southeast Asia. In: Asian Transformations: An Inquiry into the Development of Nations. Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; 504-530.

[7] Montes M. Seven Development Paths in Southeast Asia: Four Plus Three: Draft chapter presented at the Hanoi meeting of UNU/WIDER 9-10 March 2018, revised 17 June 2018.

[8] Rodrik D, Rosenzweig M. Introduction: Development Policy and Development Economics: An Introduction. In: Handbook of Development Economics. North Holland Press: Amsterdam, 2010; xv-xxviii.

[9] Nayyar D. Rethinking Asian Drama: Fifty Years Later. In: Asian Transformations: An Inquiry into the Development of Nations. Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; 3-28.

[10] Dy R. Landscape of necessity. A Tale of Two Agricultures: The Philippines and Vietnam. Accessed 04 January 2023. Available at:[Web]

[11] Adriano F. The Manila Times. Why Are We Losing in the Development Race? Accessed 04 January 2023. Available at:[Web]

[12] Fujita M, Kuroiwa I, Kumagai S. The Economics of East Asian Integration: A Comprehensive Introduction to Regional Issues. Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd: Cheltenham, UK, 2011.

[13] Athukorala P. Production Networks and Trade Patterns in East Asia: Regionalization or Globalization? AEP, 2011; 10: 65-95.[DOI]

[14] Obashi A, Kimura F. Deepening and Widening of Production Networks in ASEAN. AEP, 2017; 16: 1-27.[DOI]

[15] Obashi A. Expansion and Deepening of Production Networks. RePEc, 2020; 16: 17-46.[DOI]

[16] Asian Development Bank. Advancing Digital Services Trade in Asia and the Pacific: Proceedings of the Asian Economic Integration Report 2022. Mandaluyong, Philippines, 30 June 2022.[DOI]

[17] Yap JT. ASEAN Community 2015: Managing Integration for Better Jobs and Shared Prosperity in the Philippines. International Labor Organization Asia-Pacific Working Paper Series. International Labour Organization: Geneva, 2015.

[18] Evans P, Heller P. Introduction: The State and Development. In: Asian Transformations: An Inquiry into the Development of Nations. Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; 109-135.

[19] Dios D, Emmanuel S, Hutchcroft P. Introduction: Political Economy. In: The Philippine Economy: Development, Policies, and Challenges. Ateneo de Manila University Press: Quezon, Philippines, 2003; 45-74.

[20] Bulaong O, Mendoza G, Mendoza R. Cronyism, Oligarchy and Governance in the Philippines: 1970s vs. 2020s. Public Integrity, 2022; 26: 174-187.[DOI]

[21] Khan M. Introduction: Institutions and Development. In: Asian Transformations: An Inquiry into the Development of Nations. Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; 321-345.

[22] Fabella R. Capitalism and Inclusion under Weak Institutions. Quezon, IA: University of the Philippines; 2018.

[23] Jang J. Power-sharing in governments, clarity of responsibility, and the control of corruption. Asia Pac J Public Am, 2022; 44: 131-151.[DOI]

[24] Tigno J. The Party is Dead! Long Live the Party! Reforming the Party System in the Philippines. Quezon, IA: University of the Philippines; 2024.

[25] Beneviste J, Mizrahi S. Accountability, governance, and institutional change in intergovernmental relations: A theoretical framework. Politics Policy, 2023; 51: 242-255.[DOI]

[26] Nye J. Taking Institutions Seriously: Rethinking the Political Economy of Development in the Philippines. ADR, 2011; 28: 1.[DOI]

[27] Nayyar D. Introduction: Advance Praise for Resurgent Asia. In: Resurgent Asia: Diversity in Development. Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; iii-v.

[28] Grimes S. Asian Century on a Knife-edge: A 360 Degree Analysis of Asia’s Recent Economic Development. Eur. Plan. Stud, 2018; 1078-1079.[DOI]

[29] Angelino A, Tassinari M, Barbieri E et al. Institutional and economic transition in Vietnam: Analysing the heterogeneity in firms’ perceptions of business environment constraints. Compet Chang, 2021; 25: 52-72.[DOI]

Copyright© 2024 The Author. This open-access article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Copyright ©

Copyright ©