Healthcare Professionals’ Experiences of End-of-life Care: A Review of the Literature

Andrew Magee1#, Joanne Lusher2#*

1NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Scotland, UK

2Provost’s Group, Regent’s University London, London, UK

#Both authors contributed equally to this manuscript.

*Correspondence to: Joanne Lusher, PhD, Professor, Provost's Group, Regent’s University London, Regent's Park, London NW1 4NS, UK; Email: lusherj@regents.ac.uk

Abstract

Aims: The purpose of this review was the aggregation of empirical literature, qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods, on healthcare professionals’ experiences in end-of-life care (EOLC) in order to accentuate the need for the development of robust EOLC education and to guide future research.

Methods: A review of all empirical research published between 2014-2021 was carried out. Data sources: In June 2021, CINAHL, MEDLINE, Scopus, Health Source: Nursing / Academic Edition, Wiley Library and ERIC were searched to identify relevant studies. Review Method: Developed using Pluye and Hong (2014) to construct a mixed studies review in order to synthesise the findings of both quantitative and qualitative studies identified.

Results: Of 1,017 records identified, 20 studies met the criteria to be included within the review. Findings from the studies were then subject to thematic analysis, and quantitative data were first described to facilitate analysis. Subsequently, 7 emergent themes were formulated ‘education’; ‘allied health professionals’; ‘interprofessional cohesion’; ‘organisational considerations’; ‘patient-family communication’; ‘patient advocacy versus familial advocacy’ and ‘attitudes towards end-of-life care’.

Discussion: Education remains a key source of contention amongst healthcare professionals in EOLC, with the majority of participants feeling poorly prepared to facilitate or participate in their care. Furthermore, cultures within healthcare organisations play a significant factor in EOLC provision. A key finding that came out of this review is that a unified approach to EOLC education, both internationally and amongst professional groups, is greatly needed.

Conclusion: A key finding from this review is the need for a more unified approach to EOLC education both internationally and amongst professional groups. Further research into the role societal and cultural views has on interprofessional working is advised.

Keywords: nursing, healthcare professionals, end-of-life care, palliative care, education, interprofessional working

1 INTRODUCTION

Healthcare staff such as nurses hold both a pivotal and privileged role in providing care for those in their final days of life. Globally, the population is getting older, with the proportion of individuals over 80 years increasing by 77% between 2000 and 2015[1]. Worldwide, deaths are projected to rise from 55 million to 75 million by 2040[2]. As a direct result, both internationally and nationally, governments and their respective healthcare systems need to adapt rapidly in order to meet the demands of an increasingly older population[3]. With advances in medical science, individuals with long-term health conditions are living longer with complex illnesses that require specialist symptom management, which is increasingly delivered through palliative end-of-life care (EOLC)[4]. Despite being an inescapable and profound aspect of life, the experiences of death, dying and bereavement remain poorly investigated both within the general population and, indeed, within the healthcare community[5].

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines palliative care as an approach aimed to improve the quality of life of those patients and their families facing issues pertaining to life-threatening illness through both the prevention and relief of suffering through early identification and assessment and treatment of symptoms, as well as physical, psychosocial, and spiritual support[6]. EOLC relates to a distinctive period of the palliative care pathway[7]. Despite a lack of consensus on a specific definition of the EOLC period, it is generally accepted that EOLC begins at the point of cessation of active treatment, instead focusing on physical, spiritual, social, and emotional comfort[8]. Indeed, the European Association for Palliative Care defines EOLC as an ‘extended period of 1 to 2 years, during which the patient, family and healthcare professionals become aware of the life-limiting nature of the illnesses’. However, a National Institute for Health and Care Excellence white paper exploring EOLC service delivery describes EOLC as care provided in the last year or months of life[9]. However, despite this, EOLC is commonly used to denote the care an individual receives in their final weeks or days of life.

In Scotland, UK, for example, 50.1% (28,422) of deaths occurred within a hospital setting. Indeed, with the increasing prevalence of the population receiving EOLC in a hospital setting, it is almost inevitable that nursing staff will be involved with EOLC at some point in their career. Yet despite EOLC becoming a fundamental aspect of the nurse's role in the acute care environment, it is questionable whether the nursing workforce is equipped to deliver proficient EOLC. Generalist nurses can substantially lack knowledge in EOLC issues, impacting the quality of care delivered[10]. Furthermore, with the increase in patients receiving EOLC within a generalist environment, it is crucial that those nurses are prepared to deliver EOLC[9].

Additionally, the impact that high-quality EOLC can have in reducing unscheduled care presentation, unnecessary treatment initiation[11], and improving the quality of life of patients[12] have been discussed in the literature. Moreover, WHO recently passed a resolution that recognised EOLC as a requirement of all member countries with integration into both healthcare systems and policy[13]. To date, this remains a key priority within contemporary health and social care policy globally[14].

1.1 Background

Palliative care as a medical discipline was born out of the hospice movement in the late 1960s, Dame Cicely Saunders is widely regarded as the pioneer of the hospice movement[15]. Indeed, Saunders introduced the concept of ‘total pain’, taking into consideration not only physical pain but social, emotional, and spiritual distress. Subsequently, Balfour Mount, in the mid-1970s, coined the term ‘palliative care’ to create a distinction from hospice care as palliative care can be offered from the diagnosis of a life-limiting illness, and can be provided in tandem with life-prolonging / curative treatment. Since the inception of the hospice movement and subsequent palliative care movement, the need for effective and equitable access to EOLC has been an ever-present issue that would merit further exploration. As such, this literature review will only explore contemporary issues and emergent issues in EOLC.

Despite research literature reflecting the need for high-quality EOLC, in the past decade[16,17], EOLC has received negative attention in both the media and contemporary scholarly literature, citing poor clinical practice[18], and, more specifically, poor communication with families[19]. Internationally, the United Kingdom and its devolved nations have been regarded as leaders in highlighting the necessity of EOLC provision in healthcare policy[20]. Through Living and Dying Well, the UK’s Scottish government set the benchmark in Scotland for the expectations of EOLC in healthcare[21]. Although this action plan made strides in the advancement of palliative care in Scotland, it caused a minor improvement addressing specifically pre-registration educational issues in palliative care both for nursing and medical students. Furthermore, despite developing an educational framework being a key action point of the action plan, this would not come to fruition until almost ten years later. As Living and dying well reached the end of its implementation timeframe, the palliative and end-of-life care: strategic framework for action was launched by the Scottish government, which set out the government’s vision to improve EOLC delivery across Scotland[22]. Reiterated within this strategic framework was the need to establish standardisation of providing EOLC education for both the health and social care workforce.

Following the publication of the Francis Report[23] and Less Pathway More Care[19], UK healthcare regulators such as the Nursing and Midwifery Council began a consultation period to set new standards for pre-registration nursing programmes, which were published in 2018[24]. These standards set out what was expected of nursing programmes in developing their curricula for undergraduate and postgraduate students. Within these standards was the expectation of specific competencies to be achieved prior to registration with the NMC. Safe and effective delivery of EOLC is explicitly mentioned as a standard expected of the registered nurse encompassing technical skills and competence in psychological support for both patients and relatives.

Despite the advancements in nursing standards for education which have fundamentally changed the way in which pre-registration education is conducted, to date, there has been an absence of research conducted on exploring healthcare workers' experiences in delivering EOLC that focuses specifically on whether nursing programmes can prepare staff adequately for this specific area of clinical practice. Furthermore, with the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic and the significant impact it has had on healthcare delivery both nationally and internationally, EOLC education has never been more critical.

Existing literature highlights the impact of poor preparation for EOLC delivery on nursing staff, be it anxiety in caring for the dying patient or inadequate coping mechanisms in dealing with the death of a patient[25,26]. Researchers[27] highlight that in some instances, the grief experienced by healthcare staff can be comparable to that of a patient's own family. It has also been highlighted that those nurses delivering EOLC without formal education are likely to experience compassion fatigue and potentially burnout[28,29]. Others concur with this sentiment whilst also highlighting the importance EOLC education can have for promoting self-care of the practitioner through teaching coping strategies and resilience training to cope with nursing patients in their final days of life[30]. Indeed, an observational study found that nursing staff caring for patients receiving EOLC were more likely to utilise coping mechanisms[31].

2 METHODS

2.1 Aims

It was anticipated through conducting a structured review of the literature that a need for further research into the experiences of healthcare staff experiences of EOLC would arise alongside a necessity for further addressing the need for more robust EOLC education at the undergraduate level. This literature review therefore aimed to explore various healthcare professionals' experiences of delivering EOLC. Furthermore, this literature review aimed to critically appraise, describe, and synthesise contemporary literature surrounding healthcare professionals' experiences of delivering EOLC.

2.2 Design

A mixed studies review, a sub-type of review aiming to synthesise results from various studies using diverse designs was undertaken. This review was conducted in several stages: (1) formulation of the research question; (2) eligibility criteria; (3) applying a comprehensive search strategy; (4) identifying potentially relevant studies; (5) selection of relevant studies; (6) appraisal of the quality of the included studies; and (7) synthesis of the included study's findings[32,33]. This method was appropriate for the present literature review due to the mixed method approach it adopted. Throughout the review, frequent contact was maintained between two independent reviewers to facilitate the progression and quality of the literature review. Data gathered were subsequently analysed using a thematic analysis approach.

The review was formulated to answer the following question: What are healthcare professionals' perceptions of their education, understanding, and experience in delivering end-of-life care?

2.3 Eligibility Criteria

Following the formulation of the research question, the second stage of the review involved formulating the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the search. The review criteria were formulated prior to undertaking the literature search and were shaped by the aim of the review. The population being explored within the search was broad to allow for a comparison of EOLC education and experience amongst the healthcare team. Furthermore, this broad multi-professional audience was included on the basis of an ever-growing recognition of the value of a multidisciplinary approach in delivering quality EOLC[34]. The research explored knowledge, experiences, and education of EOLC as perceived by healthcare professionals. Research pertaining to the provision of EOLC to adults was included in any setting (with exception to those discussed in the exclusion criteria). Studies were only included if they were empirical, full-text, peer-reviewed, and written in English. Studies relating to neonatal / paediatric EOLC were excluded. Studies exploring patients' experiences of EOLC were also excluded, with the exception of those incorporating health professionals' perspectives if their views were presented independently.

Inclusion Criteria

● Publication date range: 2014-2021

● Studies relating to healthcare professionals' experiences

● Provision of end-of-life care to adults (>18 years of age)

● Empirical, full-text and peer-reviewed

● Written in English language

Exclusion Criteria

● Studies exploring the provision of EOLC solely to neonatal / paediatric patient groups

● Studies exploring patients' experiences of EOLC (except those incorporating health professionals’ perspectives if their views were presented independently)

Within the third stage of the review, an extensive literature search was conducted. The time period utilised within the search was 2014-2021. This range was necessary to allow both incorporations of a timeframe reflective of current developments in EOLC and allow a sufficient body of research to allow for review as EOLC research relating to health professionals' perceptions remains an under-investigated area[35]. Furthermore, this timeframe was utilised to coincide with changes in the educational requirements of the NMC for pre-registration nursing students within the UK[36]. However, given the shortage of literature produced within the UK alone, consideration was given to expanding the geographical area included in the search to facilitate a sufficient pool of literature.

A computerised database search was carried out incorporating the CINAHL, MEDLINE, Scopus, Health Source: Nursing / Academic Edition, Wiley Library and Education Resource Information Centre (ERIC). The selection of the above databases was established according to subject appropriateness and comprehensiveness[33]. Utilisation of the PICO framework aided search strategy formulation (see Table 1). Alongside this, other search strategies included hand-searching of journals and reference lists. Searches used free text words, modified as appropriate. Given the interchangeable usage between both palliative care and EOLC[37], the phrase palliative care was employed in the search to ensure relevant studies were not excluded from the review. Boolean operators were also employed to focus the search.

Table 1. Search Strategy

1 |

Health Personnel or Allied Health Personnel or Medical Staff or Nurs* or Physicians |

2 |

Adult |

3 |

Palliative care or terminal care or hospice care or degenerative illness |

4 |

Perspective or experience or attitude |

5 |

Education or training or confidence or competence or knowledge |

6 |

1 and 2 and 3 and 4 and 5 |

3 RESULTS

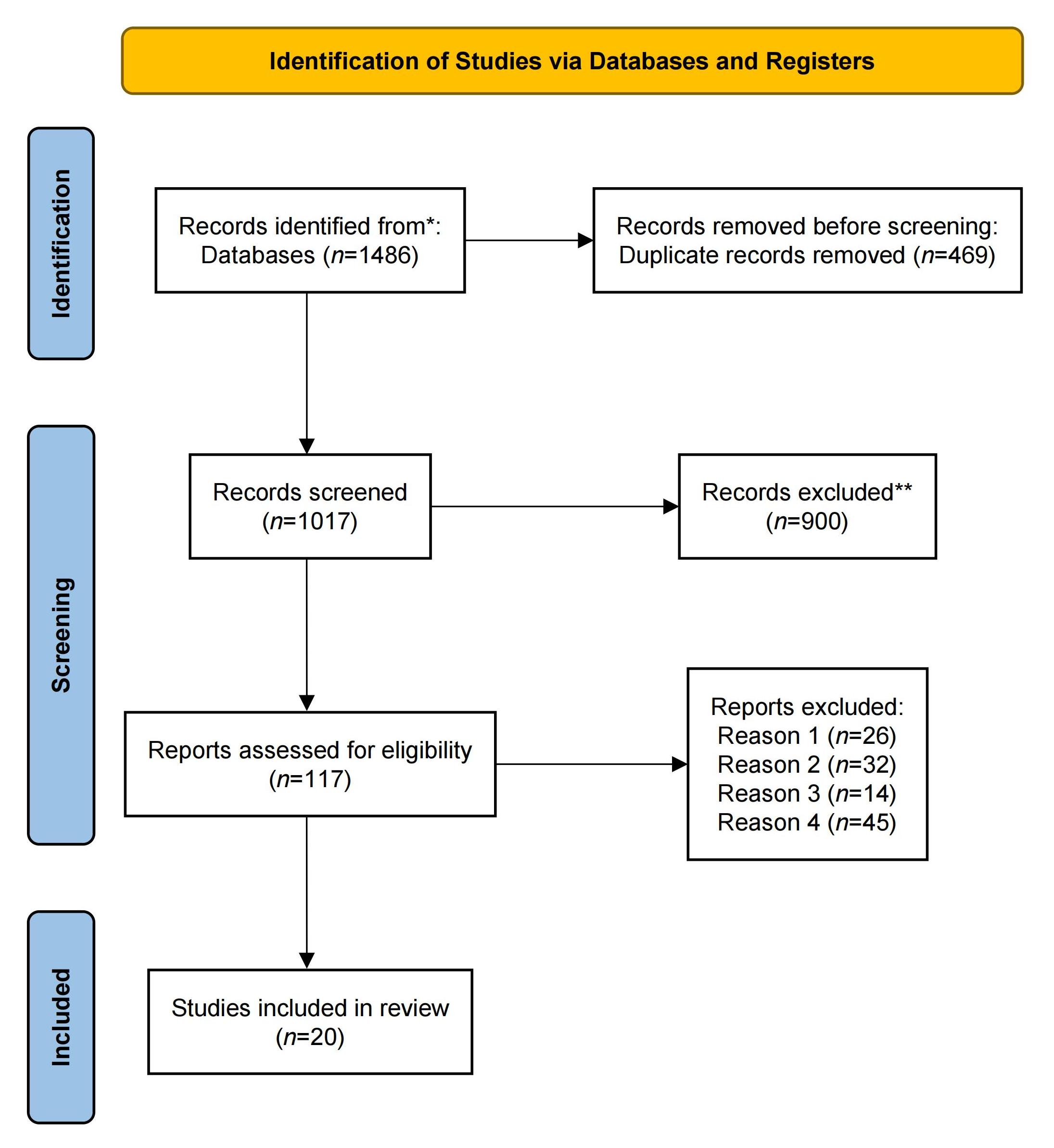

Screening of both titles and abstracts was undertaken independently by two independent reviewers. Subsequently, a full-text review was undertaken to determine studies suitable for inclusion. A flow chart (see Figure 1) was utilised to depict the process of the literature selection process, and this is reflective of both the final stages of the review[33]. A total of 1017 records were screened for suitability in the literature review, 117 were screened for eligibility and 20 articles met the inclusion criteria. Reasons for exclusion at this stage of the screening process were reason: (1) the primary exploration was an education intervention; (2) patient experience was the primary focus; (3) the focus was solely paediatric; and (4) EOLC was not the primary focus of the research (see Figure 1 for flow chart and Table 1 for summary table).

|

Figure 1. PRISMA flow.

3.1 Quality Appraisal

The sixth stage of the review process consisted of a critical appraisal of the data conducted by employing the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist tools for quality appraisal in qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method studies[38]. Usage of the CASP checklist has proven to be a valid and reliable method for the appraisal of various study types[39].

3.2 Data Abstraction

The included studies were described by extracting data (author, year, country, aim, methodological approach, sample, and key findings). In accordance with the literature review approach employed, quantitative data were first described descriptively. Following this, data were extracted from all studies; qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods.

3.3 Synthesis

Inductive thematic qualitative synthesis was undertaken, which is a form of convergent synthesis to allow for analysis of the quantitative and mixed method findings in a qualitative context. Quantitative data were then converted into narrative to allow synthesis of the data[33]. Due to themes being identified based on the data and not a pre-defined theory, inductive synthesis was utilised. This required repeated reading of study findings and this data being extracted into tables. Meaningful entities from the findings were then coded, and similar findings were grouped together to form preliminary themes. These early themes underwent revision prior to the final review. The synthesis of the data extrapolated was iterative.

3.4 Description of the Studies

An overview of the five quantitative studies included studies conducted over a wide geographical area. This was purposeful to allow comparison of EOLC provision internationally. One study was conducted in Saudi Arabia, two in the United States, one in Sweden, and one in Malaysia. All five studies utilised descriptive questionnaires, or surveys. Questionnaires used included the palliative care quiz for nurses (PCQN), the EOLC questionnaire and format attitudes toward care of the dying scale. Participants within the quantitative studies were exclusively registered nurses, with the exception of one study, which had a broad range of healthcare professionals who participated[40]. Sample size ranged from 76 to 1,197. Experience (years of clinical practice) of participants varied greatly, although important to note not all surveys employed these demographics. Settings for these studies were broad encompassing numerous areas of clinical practice and specialities, with the exception to one that focused solely on the intensive care environment[41]. Limitations of the included studies included both low response rates and poor validity, and alteration of established instruments also impacted on validity. Furthermore, poor responses from individual professional groups contributed to researchers being unable to provide sufficient data to allow analysis.

As with the quantitative studies, a purposeful selection of studies over a wide geographical area was employed. Of the 12 studies included, three were conducted in the UK and Australia. Studies included involved a range of methodological designs, including grounded theory, phenomenology, qualitative exploratory descriptive, interpretative, naturalistic inquiry, and inductive approaches. Years in clinical practice varied greatly among participants, ranging from one year to 35 years, although important to note given the multitude of professional groups amongst the studies, it is difficult to give specificities of the demographic of each group. There were three mixed methods designs incorporated, with two focusing exclusively on nursing staff and the other incorporating all professional groups.

Seven themes were identified regarding EOLC provision amongst the reviewed literature, and these were discovered inductively. Themes included: education, allied health professionals (AHPs), interprofessional cohesion, organisational considerations, patient / family communication, patient advocacy versus familial advocacy and attitudes towards EOLC.

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Education

Repeatedly emphasised amongst the research literature was the need to improve the provision of EOLC education into the curricula of various pre-registration health professionals. This recommendation for pre-registration EOLC teaching is echoed amongst the reviewed literature[41-44]. The notion of integration of EOLC education is highlighted by all healthcare professionals across the studies, interestingly highlighting a uniform self-reported need for EOLC education both pre- and post-registration[44,45].

The reported lack of educational support in pre-registration programmes often led to health professionals feeling underprepared and, as described in one study, frustrated at their lack of knowledge in delivering patient care[44]. This sentiment of perceived lack of knowledge was shared amongst the studies reviewed encompassing all disciplines[46-49]. However, the perceived lack of education varied greatly amongst the health professionals participating. Nursing staff were likely to report feeling poorly prepared to deliver overall management of EOLC[48] as well as more specific skills such as communicating bad news[50-53] and symptom management[54,55].

Registered nurses and nursing students commonly reported a lack of knowledge in the encompassing philosophy of palliative care and the skills to emotionally support both patients and their families[56-58]. However, physicians in contrast reported poor knowledge in identifying when a patient was actively dying and knowledge of the dying process[42]. Junior medical staff highlighted this as a significant barrier to effective EOLC delivery[57]. This view is also identified elsewhere among junior doctors reporting great uncertainty and anxiety of assessing the dying patient for fear of misdiagnosis of the dying process[42], identifying a need for greater educational input in teaching medical students an approach to identifying the dying patient both through theoretical teaching and experiential learning in clinical practice. Interestingly nursing staff were more likely to report greater self-perceived knowledge in symptom management than medical staff within some studies[40,49].

Methods of education delivery were discussed sparingly within the literature, with some studies finding participants' preferences. Nursing staff voiced a preference for experience shadowing senior nursing staff or being mentored in EOLC[11,44]. Experiential learning is a commonly utilised method within the nursing profession, with nurses historically having a preference for more ‘hands on’ methods of learning[50]. Nursing staff reported the positive impact observing senior nursing staff had on their practice and often looked for peer support in developing their practice[58]. Medical staff, however, reported a preference for a combination of a structured didactic approach for theoretical aspects such as symptom management[47,57] and experiential / observational learning for skills such as communicating bad news through observing senior medical staff[42,47]. Although there remains variance in the methods by which differing professional groups prefer education delivery, what is highlighted is the reported need for education in core skills such as communication, symptoms management and psychological / emotional support amongst all professional groups. As such, consideration must be given to supporting both the core learning needs required by all clinicians, with additional / role-specific needs being identified to both facilitate appropriate individualised learning whilst also ensuring all clinicians receive some degree of core training.

Although most studies highlighted a need for a more rigorous approach to education in EOLC, participants across the studies emphasised their perceived necessity of incorporating gaining experience in observing and delivering EOLC. Junior medical staff shadowing more senior medical staff has been found to facilitate development in approaches to communicating bad news effectively and the value placed on informal learning opportunities[47]. This is unsurprising given previous research emphasises the important role observation in practice plays in the education of pre-registration clinicians both in clinical practice and simulation[59]. Junior medical staff reported that although observing good practice in respect of delivering bad news to patients / relatives was valuable to their learning, they considered the observation of poor practice equally valuable as a means of observing what not to adopt in terms of approaches to communicating bad news[42,47].

Although more traditional didactic teaching may foster an increase in EOLC knowledge, the ability to successfully integrate this into clinical practice requires the opportunity to practice under supervision. Without structured learning in place, those clinicians early in their practice often adopted a trial-and-error approach in delivering EOLC[44,45]. Unsurprisingly, this approach to clinical skills has been criticised amongst the research literature as leading to insufficient, variable, and inappropriate EOLC provision[11,57,60].

4.2 Allied Health Professionals

Greatly underrepresented amongst the literature are participants belonging to the AHPs umbrella encompassing physiotherapists, occupational therapists, social workers, and psychologists[40,46,49]. However, it is important to highlight this could be reflective of the scope of each discipline in delivering clinical care within their respective organisations. Equally, low responses from AHP’s could be reflective of a reluctance to participate due to a lack of confidence in EOLC. Furthermore, both physiotherapists and occupational therapists have been found to have the lowest self-perceived scores in knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours, although due to the relatively low response rate from these clinicians, it would be erroneous to draw generalisations from this data, this limitation is recognised by the researchers[40].

4.3 Interprofessional Cohesion

Within the modern healthcare environment, the input and care delivered by various health professionals are considered imperative in effective care delivery[53]. Yet despite this, internationally, divisions remain in healthcare and often at the detriment of clinical care[61,62]. Furthermore, nursing staff have reported medical staff to have a poor understanding of the nursing role, often undermining them and not considering their input[51]. Cultural factors have been highlighted to significantly impact both interprofessional working and consequentially the provision of EOLC[41,54,63]. This sentiment is also highlighted by a study carried out within Australia[60]. Interestingly, although nursing staff perceived their input as being disregarded or unwanted by medical staff, medical staff reported the input of nursing staff as invaluable in their decision-making process. This highlights the importance of feedback amongst clinicians to facilitate and allow clinicians to feel heard[64]. Similarly, another study found that physicians were disinterested in EOLC and often left the nursing staff to manage all aspects of care, with physicians only then providing input with symptom management and confirmation of death[54].

4.4 Organisational Considerations

Scholars discuss the growing need for EOLC amongst an array of healthcare settings and specialities[55]. Yet despite increasing integration, utilisation of EOLC is often implemented late in a patient's deterioration, where it would have been beneficial for earlier intervention[46,57,60]. Other studies have highlighted within their study those clinicians working in an acute surgical environment often viewed cessation of treatment and EOLC as a failure in their practice[11]. Although this can be attributed to these acute areas having a heavy emphasis on curative intent[55], this negative attitude towards EOLC could be attributed to a poor understanding of the philosophy of both palliative and EOLC generally.

Furthermore, with participants amongst the studies reporting EOLC being identified late in the dying process, this can result in poor symptom management, which can be distressing to not only patients and relatives but also clinicians[34,48,51,63]; and nursing an individual at end-of-life can be challenging within the critical care environment[52]. Concerns were also raised among participants over the changing of consultant intensivists on a weekly basis, with some changing patients' care from end-of-life to curative based on their clinical judgement. This uncertainty created great animosity amongst nursing staff with the lack of a standard approach to EOLC decisions. However, medical staff rationalised this within the study by discussing fluctuations in a patient’s condition and the need to assess patients individually.

A commonly reported barrier to effective EOLC amongst nursing staff is workload allocation, often with considerable time being spent with those patients receiving curative treatment leaving little time to spend with those patients receiving EOLC[11,52]. Andersson et al.[11] go on to discuss that amongst participants, this caused some frustration and led to perceptions they were not adequately caring for their patients. Additionally, frustrations of nursing staff at not having adequate time to spend with those patients receiving EOLC[41]. Yet despite this, less experienced nursing staff tend to favour carrying out technical nursing care often at the expense of holistic care, which is crucial in all care delivery but especially EOLC[54]. This could be attributed to task avoidance due to discomfort in caring for the dying patient, which was reported by another[63].

Another relationship discovered was between clinical area and confidence in performing EOLC. Individuals working in areas where EOLC was not commonly reported had poorer knowledge[58], confidence[48] and attitude[44] towards EOLC. It has been asserted that those with little clinical exposure to EOLC, unsurprisingly, were the least likely to exhibit confidence in EOLC delivery[48]. This raises a concern over whether pre-registration education would make a significant difference to EOLC provision, as the research literature shows those who do not experience EOLC in professional practice on a semi-regular basis are more likely to report a lack of competence.

4.5 Patient-family Communication

Effective communication between healthcare professionals is often considered an integral aspect of good care delivery. Yet despite this, communication in EOLC has often been portrayed as a critical element in failures of care[20]. As highlighted within the studies, communication is commonly discussed as an area many healthcare professionals are both undereducated and anxious to carry out[44,51,52,57]. Having significant conversations regarding patient deterioration and cessation of active treatment are often crucial moments in EOLC[42,57], yet despite this, many of the participants in the studies highlighted feeling poorly prepared to carry this out and often reluctant to do it.

Junior medical staff often rely on observing more senior medical staff having these significant conversations and adopting good practices whilst identifying poor practices. This often hap-hazard approach to gaining experience is also identified amongst the literature for both nursing and medical staff[11,34]. Morgan et al.[46] found that participants found value in observing recorded patient-clinician interactions first by an inexperienced clinician followed by an example from an experienced clinician. Participants have also highlighted the value found in utilising creative methods of teaching, including the above alongside role-playing[43] and using simulation as an additional useful tool[59].

Moreover, poor communication from medical staff to families can have a negative impact on both patient and family experiences[41]. Poor communication of significant changes in care, such as cessation of active treatment and implementation of do not resuscitate orders, can cause significant distress to patients and families, especially in the event the patient dies, as families may question why resuscitation is not being attempted, which can be a significant source of contention amongst medical and nursing staff[41].

4.6 Patient Advocacy Versus Familial Advocacy

All clinicians, regardless of individual professional grouping or seniority, are duty-bound to deliver both safe and effective care to their patients, as well as advocate for care in their best interest. Yet despite this, within explored research, variations and conflicts surrounding advocacy exist. Highlighted within the studies reviewed was a significant division amongst clinicians on who primarily advocacy should be best aimed at, the patient or their families. Participants often advocated for early cessation of treatment at the earliest indication of treatment futility[60]. Conversely, medical staff were inclined to prolong treatment in order to allow patients’ families time to accept -often through direct observation of their relative declining or failing to respond to treatment - that treatment was futile and thus allow them time to come to terms that treatment cessation is in the patient’s best interest[41,51].

This prolongation of treatment was a significant point of contention in the literature amongst nursing staff reporting both frustration and concern at the prolongation of patient suffering in favour of easing familial suffering[41,49,51]. Although medical staff may view this as advocacy of the family, this is often at the expense of the patient and raises significant ethical concerns regarding inappropriate and prolonged care delivery with little benefit[65,66]. Equally, this is another example of contention amongst nursing and medical staff, with nurses reporting feeling they have little say over clinical decision-making, despite having a high degree of autonomy in other areas of practice and equally spending the most time with the patient and family[41]. However, both nursing and medical staff have felt they share equal views in decision-making[49]. This suggests issues pertaining to decision-making may be reflective of geographical differences in role awareness instead of implicitly relating to EOLC. As such consideration must be given to addressing barriers in decision-making amongst health professionals and the need for shared decision-making.

4.7 Attitudes Towards EOLC

Despite EOLC becoming a significant aspect of care delivery amongst all health professionals across a wide spectrum of clinical areas, attitudes towards EOLC remain greatly varied. Clinicians working in acute clinical areas were often the most likely to view EOLC negatively and as a failure in their care. Participants highlight that surgeons often favour spending time with patients undergoing treatment with curative intent, often forgoing time with those patients in EOLC[11]. This was especially true amongst the studies carried out in critical care areas[34,41,49,51,52], although this is not surprising given the aggressive pursuit of treatment commonly found in these areas[38]. Furthermore, similar values amongst clinicians working in the critical care setting were found to improve interprofessional cohesiveness and equally job satisfaction[34,49]. This sentiment of increased job satisfaction in effective EOLC provision is echoed elsewhere[11].

Additionally, attitudes amongst nursing staff towards EOLC changed positively with experience[58]. This could be rationalised by witnessing the futility of aggressive treatment in the already dying patient or the suffering experienced by those patients not receiving adequate symptom management. Equally, those clinicians who participated in post-graduate education in EOLC had improved attitudes towards EOLC[46,48,58]. There is a correlation amongst those individuals that had undertaken further study in EOLC and attitudes towards EOLC, noting that scoring on the scale was higher amongst this group than both those with no education and those who undertook "in-house" training[58]. However, nursing participants within one study reported, in comparison to physicians, they had considerably more in-service EOLC education[49]. Yet despite this, nursing staff reported significant gaps in knowledge relating to communicating bad news. As such, consideration must be given when delivering in-service education to deliver education to meet the needs of the applicable workforce.

Furthermore, understanding of the philosophy of the broader umbrella of palliative care was commonly found to be poor amongst the studies reviewed. A couple of studies have highlighted that of those surveyed, one of the lowest scoring perceived competencies was on underpinning philosophy of EOLC[56,58]. This is not surprising given the ingrained attitude of EOLC being viewed as a transition point of care rather than a trajectory-based approach[68]. Cultural differences may actively hinder the implementation of EOLC, with favour given to pursuing aggressive treatment until death is imminent[41,51]. Desire to prolong life at all costs may stem from both religious[41] and cultural beliefs[51], and as such, EOLC education is crucial to sensitively explore these viewpoints to facilitate effective patient care.

Further to this, interpretations of EOLC varied greatly amongst the participants, with medical and nursing staff focussing heavily on symptom management and relief of suffering, often at the expense of promotion of quality of life - from the perspective of emotional and psychological support - or the role communication plays in this significant episode in life[44,46,47]. Furthermore, the ability of clinicians to define both palliative and EOLC remains difficult, with generalist clinicians commonly referring to EOLC as a specialist service rather than simply a philosophy and form of care practice[58].

The demand for EOLC has rapidly increased over recent decades[3,13]. This is consequentially due to population growth and increasing life expectancy with the concurrent increase in long-term conditions[69]. However, despite increasing demand for EOLC within Scottish services providing specialist EOLC, be it hospice or in-home, has not grown with demand. As such, a significant proportion of individuals dying are spending their final days within the hospital environment.

Despite EOLC becoming an integral aspect of the registered nurse's role, research highlights the disparity between the educational and clinical environments in EOLC education for nursing students[11]. However, a lack of preparation amongst nurses in delivering EOLC can lead to anxiety, stress, and burnout[70]. In accordance with both publication of new pre-registration education standards for nursing students and governmental policy in the UK particularly, many higher educational institutions are further integrating EOLC into their curricula.

5 CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS FOR HEALTHCARE PRACTICE

This literature review has explored the experiences of various health professionals' experiences of EOLC. Perhaps due to the nature of EOLC, participation of both nursing and medical staff was higher than AHP participation. Although a multidisciplinary approach has been regarded as promoting effective care for the patient in EOLC, the findings from this review cast doubt over AHP involvement. Overall, health professionals scored poorly for both self-reported knowledge and competency in EOLC. However, participation from AHPs was low across the included research, and as such, generalisations cannot be drawn, and this is discussed within the limitations of the studies involving AHPs. Thus, further investigation into AHPs' experiences, as well as examining knowledge in EOLC would be advisable.

Of the included studies, 12 utilised varied qualitative approaches in exploring experiences in EOLC, allowing a rich dataset for the literature review and subsequent thematic analysis. However, often discussed within the limitations of these studies is the limitation of utilising only a qualitative approach. This is equally true of the quantitative studies using instruments relating to self-perceived competency, knowledge, and attitudes. Given the value of the data found within the mixed method studies, utilisation of a knowledge-assessing instrument such as the PCQN would be beneficial in increasing the validity of the findings.

Despite the wide geographical coverage of this literature review, both the qualitative findings and quantitative findings did not vary greatly from country to country. The only exception to this was the study conducted within Malaysia[51] and a study conducted in Saudi Arabia[41]. Reasoning for this is given within both studies relating to both the nature of developing healthcare systems within the countries and public attitudes towards EOLC provision. However, the remaining studies showed great similarities in health professionals’ experiences in EOLC, namely, a lack of confidence and a self-reported lack of sufficient education. Despite the WHO proclaiming the need for all member countries to consider PEOLC a universal necessity in modern healthcare delivery, it remains apparent that EOLC provision is still being significantly hindered in part by healthcare professionals’ lack of both knowledge and experience in delivering it.

Finally, cultures within healthcare organisations have also been highlighted as being critical to EOLC. Despite Interprofessional working being the gold standard of effective care delivery, nursing staff reported feeling both unheard and unappreciated in the decision-making processes of EOLC[49,54]. This could be attributable to deep-rooted societal values, this alongside nursing remaining a predominately female-populated field in comparison to medicine, although important to note this cannot be generalised as the study was only conducted in one geographical area. As such, further research should be carried out to investigate specifically the role that societal and cultural views have on interprofessional work.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Author Contribution

Magee A and Lusher J administrated this project and supervised by Lusher J. Magee A was responsible for conceptualisation, methodology and data curation, then validated by Lusher J. Original draft was done by Magee A and Lusher J. Following review and editing were completed by Lusher J. Both authors have read and agreed to this published version of the manuscript.

Abbreviation List

AHP, Allied Health Professional

EOLC, End-of-life care

PCQN, Palliative care quiz for nurses

WHO, World Health Organization

References

[1] Desa U. World population ageing 2015. United Nations DoEaSA, population division editor, 2015; 2015: 1-159.[DOI]

[2] Foreman KJ, Marquez N, Dolgert A et al. Forecasting life expectancy, years of life lost, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 250 causes of death: reference and alternative scenarios for 2016-40 for 195 countries and territories. Lancet, 2018; 392: 2052-2090.[DOI]

[3] Etkind SN, Bone AE, Gomes B et al. How many people will need palliative care in 2040? Past trends, future projections and implications for services. BMC Med, 2017; 15: 102.[DOI]

[4] Hall MA. Critical Care Registered Nurses' Preparedness in the Provision of End-of-Life Care. Dimens Crit Care Nur, 2020; 39: 116-125.[DOI]

[5] Ke LS, Huang X, O'Connor M et al. Nurses' views regarding implementing advance care planning for older people: a systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies. J Clin Nurs, 2015; 24: 2057-2073.[DOI]

[6] World Health Organisation. Palliative Care. Accessed 6 May 2021. Available at:[Web]

[7] Radbruch L, Payne S. White Paper on standards and norms for hospice and palliative care in Europe: part 1. Eur J Palliat Care, 2009; 16: 278-289.

[8] Noome M, Dijkstra BM, Leeuwen E et al. Exploring family experiences of nursing aspects of end-of-life care in the ICU: A qualitative study. Intens Crit Care Nur, 2016; 33: 56-64.[DOI]

[9] NICE. End of life care for adults: service delivery. Accessed July 2023. Available at:[Web]

[10] Finucane AM, Bone AE, Evans C J et al. The impact of population ageing on end-of-life care in Scotland: projections of place of death and recommendations for future service provision. Bmc Palliat Care, 2019; 18: 112.[DOI]

[11] Andersson E, Salickiene Z, Rosengren K. (2016) To be involved-A qualitative study of nurses' experiences of caring for dying patients. Nurs Educ Today, 2016; 38: 144-149.[DOI]

[12] Mason B, Kerssens JJ, Stoddart A et al. Unscheduled and out-of-hours care for people in their last year of life: a retrospective cohort analysis of national datasets. Bmj Open, 2020; 10: e041888.[DOI]

[13] Karbasi C, Pacheco E, Bull C et al. Registered nurses' provision of end-of-life care to hospitalised adults: A mixed studies review. Nurs Educ Today, 2018; 71: 60-74.[DOI]

[14] Inbadas H, Carrasco JM, Gillies M et al. The level of provision of specialist palliative care services in Scotland: an international benchmarking study. Bmj Support Palliat, 2018; 8: 87-92.[DOI]

[15] Kennedy C, Brooks-Young P, Gray C et al. Diagnosing dying: an integrative literature review. Bmj Support Palliat, 2014; 4: 263-270.[DOI]

[16] Krawczyk M, Wood J, Clark D. Total pain: Origins, current practice, and future directions. Omsorg: Norw J Palliat Care, 2018; 2018(2).

[17] Collins H, Raby P. Palliative care after the Liverpool Care Pathway: a study of staff experiences. Br J Nurs, 2019; 28: 1001-1007.[DOI]

[18] Rolt L, Gillett K. Employing newly qualified nurses to work in hospices: A qualitative interview study. J Adv Nurs, 2020; 76: 1717-1727.[DOI]

[19] Leigh J, Roberts D. Critical exploration of the new NMC standards of proficiency for registered nurses. Br J Nurs, 2018; 27: 1068-1072.[DOI]

[20] Neuberger J, Guthrie C, Aaronovitch D et al. More care, less pathway: a review of the Liverpool Care Pathway. Department of Health, Great Britain, UK, 2013.

[21] Gardiner C, Gott M, Ingleton C et al. Extent of palliative care need in the acute hospital setting: A survey of two acute hospitals in the UK. Palliative Med, 2013; 27: 76-83.[DOI]

[22] Scottish Government. Living and Dying Well: A national action plan for palliative and End-of-Life care in Scotland. Assessed October 25 2008. Available at:[Web]

[23] Scottish Government. Palliative and End-of-Life care: strategic framework for action. Assessed June 2011. Available at:[Web]

[24] Francis R. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust public inquiry: executive summary. The Stationery Office, UK, 2013.

[25] Gambles MA, Mcglinchey T, Aldridge J et al. Continuous quality improvement in care of the dying with the Liverpool Care Pathway for the Dying Patient. Int J Care Pathways, 2009; 13: 51-56.[DOI]

[26] Li J, Smothers A, Fang W et al. Undergraduate Nursing Students' Perception of End-of-Life Care Education Placement in the Nursing Curriculum. J Hosp Palliat Nurs, 2019; 21: E12-E18.[DOI]

[27] Boerner K., Burack OR, Jopp DS et al. Grief After Patient Death: Direct Care Staff in Nursing Homes and Homecare. J Pain Symptom Manag, 2015; 49: 214-222.[DOI]

[28] Cross LA. Compassion Fatigue in Palliative Care Nursing: A Concept Analysis. J Hosp Palliat Nurs, 2019; 21: 21-28.[DOI]

[29] Cedar S, Walker G. Protecting the wellbeing of nurses providing end-of-life care. Nurs Times, 2020; 116: 36-40.

[30] Gillman L, Adams J, Kovac R et al. Strategies to promote coping and resilience in oncology and palliative care nurses caring for adult patients with malignancy: a comprehensive systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep, 2015; 13: 131-204.[DOI]

[31] Sudbury-Riley L, Hunter-Jones P. Facilitating inter-professional integration in palliative care: A service ecosystem perspective. Soc Sci Med, 2021; 277: 113912.[DOI]

[32] Kim S, Lee K, Kim S. Knowledge, attitude, confidence, and educational needs of palliative care in nurses caring for non-cancer patients: a cross-sectional, descriptive study. Bmc Palliat Care, 2020; 19: 105.[DOI]

[33] Pluye P, Hong QN. Combining the Power of Stories and the Power of Numbers: Mixed Methods Research and Mixed Studies Reviews. Annu Rev Publ Health, 2014; 35: 29-45.[DOI]

[34] Holms N, Milligan S, Kydd A. A study of the lived experiences of registered nurses who have provided end-of-life care within an intensive care unit. Int J Palliat Nurs, 2014; 20: 549-556.[DOI]

[35] Hertanti NS, Wicaksana AL, Effendy C et al. Palliative care quiz for Nurses-Indonesian Version (PCQN-I): A cross-cultural adaptation, validity, and reliability study. Indian J Palliat Car, 2021; 27: 35-42.[DOI]

[36] Leigh J, Roberts D. Implications for operationalising the new education standards for nursing. Br J Nurs, 2017; 26: 1197-1199.[DOI]

[37] Todaro-Franceschi V. Critical care nurses’ perceptions of preparedness and ability to care for the dying and their professional quality of life. Dimens Crit Care Nur, 2013; 32: 184-190.[DOI]

[38] Long HA, French DP, Brooks JM. Optimising the value of the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis. Res Methods Med Health Sci, 2020; 1: 31-42.[DOI]

[39] Price S, Schofield S. How do junior doctors in the UK learn to provide End-of-Life care: a qualitative evaluation of postgraduate education. Bmc Palliat Care, 2015; 14: 45.[DOI]

[40] Montagnini M, Smith HM, Price DM et al. Self-Perceived End-of-Life Care Competencies of Health-Care Providers at a Large Academic Medical Center. Am J Hosp Palliat Me, 2018; 35: 1409-1416.[DOI]

[41] Mani ZA, Ibrahim MA. Intensive care unit nurses’ perceptions of the obstacles to the End-of-Life care in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J, 2017; 38: 715-720.[DOI]

[42] Kallio H, Pietilä AM, Johnson M et al. Systematic methodological review: developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J Adv Nurs, 2016; 72: 2954-2965.[DOI]

[43] Jors K, Seibel K. Bardenheuer H et al. Education in End-of-Life Care: What Do Experienced Professionals Find Important? J Cancer Educ, 2016; 31: 272-278.[DOI]

[44] Croxon L, Deravin L, Anderson J. Dealing with end of life-New graduated nurse experiences. J Clin Nurs, 2018; 27: 337-344.[DOI]

[45] McCourt R, Power JJ, Glackin M. General nurses' experiences of end-of-life care in the acute hospital setting: a literature review. Int J Palliat Nurs, 2013; 19: 510-516.[DOI]

[46] Morgan DD, Litster C, Winsall M et al. “It’s given me confidence”: a pragmatic qualitative evaluation exploring the perceived benefits of online end‐of‐life education on clinical care. Bmc Palliat Care, 2021; 20: 57.[DOI]

[47] Frearson S. Education and Training: Perceived educational impact, challenges and opportunities of hospice placements for foundation year doctors: a qualitative study. Future Healthc J, 2019; 6: 56-60.[DOI]

[48] Nursing and Midwifery Council. Realising professionalism: Standards for education and training Part 3: Standards for pre-registration nursing programmes. UK, 2018

[49] Riegel M, Randall S, Ranse K et al. Healthcare professionals' values about and experience with facilitating end-of-life care in the adult intensive care unit. Intens Crit Care Nurs, 2021; 65: 103057.[DOI]

[50] Murray M, Stone A, Pearson V et al. Clinical solutions to chronic pain and the opiate epidemic. Prev Med, 2019; 118: 171-175.[DOI]

[51] Utami RS, Pujianto A, Setyawan D et al. Critical Care Nurses’ Experiences of End-of-Life Care: A Qualitative Study. Nurse Media J Nurs, 2020; 10: 260-274. [DOI]

[52] Kisorio LC, Langley GC. Intensive care nurses' experiences of end-of-life care. Intens Crit Care Nurs, 2016; 33: 30-38.[DOI]

[53] Stokes J, Kristensen SR, Checkland K et al. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary team case management: difference-in-differences analysis. BMJ Open, 2016; 6: e010468.[DOI]

[54] Prades J, Remue E, Van Hoof E et al. Is it worth reorganising cancer services on the basis of multidisciplinary teams (MDTs)? A systematic review of the objectives and organisation of MDTs and their impact on patient outcomes. Health Policy, 2015; 119: 464-474.[DOI]

[55] Fristedt S, Grynne A, Melin-Johansson C et al. Registered nurses and undergraduate nursing students' attitudes to performing end-of-life care. Nurse Educ Today, 2021; 98: 104772.[DOI]

[56] Cleary AS. Graduating nurses' knowledge of palliative and end-of-life care. Int J Palliat Nurs, 2020; 26: 5-12.[DOI]

[57] Redman M, Pearce J, Gajebasia S et al. Care of the dying: a qualitative exploration of Foundation Year doctors’ experiences. Med Educ, 2017; 51: 1025-1036.[DOI]

[58] Wilson O, Avalos G, Dowling M. Knowledge of palliative care and attitudes towards nursing the dying patient. Br J Nurs, 2016; 25: 600-605.[DOI]

[59] Dixon J, King D, Matosevic T et al. Equity in the provision of palliative care in the UK: review of evidence. Personal Social Services Research Unit, London School of Economics and Political Science, UK, 2015.

[60] Flannery L, Peters K, Ramjan LM. The differing perspectives of doctors and nurses in end-of-life decisions in the intensive care unit: A qualitative study. Aust Crit Care, 2020; 33: 311-316.[DOI]

[61] Powell AE, Davies H. The struggle to improve patient care in the face of professional boundaries. Soc Sci Med, 2012; 75: 807-814.[DOI]

[62] Sudbury-Riley L, Hunter-Jones P. Facilitating inter-professional integration in palliative care: A service ecosystem perspective. Soc Sci Med, 2021; 277: 113912.[DOI]

[63] Hussin E, Wong L, Chong M et al. Factors associated with nurses’ perceptions about quality of end-of-life care. Int Nurs Rev, 2018; 65: 200-208.[DOI]

[64] Rapin J, Pellet J, Mabire C et al. How does feedback shared with interprofessional healthcare teams shape nursing performance improvement systems? A rapid realist review protocol. Syst Rev-London, 2019; 8: 182.[DOI]

[65] Akdeniz M, Yardımcı B, Kavukcu E. Ethical considerations at the end-of-life care. SAGE Open Med, 2021; 9: 20503121211000918.[DOI]

[66] Jox RJ, Horn RJ, Huxtable R. European perspectives on ethics and law in end-of-life care. Handb Clin Neurol, 2013; 118: 155-165. [DOI]

[67] Standing H, Patterson R, Lee M et al. Information sharing challenges in end-of-life care: a qualitative study of patient, family and professional perspectives on the potential of an Electronic Palliative Care Co-ordination System. BMJ Open, 10: e037483.[DOI]

[68] Lynn J, Adamson DM. Living well at the end of life. Adapting healthcare to serious chronic illness in old age. Santa Monica: Rand, 2003.

[69] O'Shea E, Campbell S, Engler A et al. Effectiveness of a perinatal and pediatric End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC) curricula integration. Nurs Educ Today, 2015; 35: 765-770.[DOI]

[70] Mak Y, Chiang, V, Chui W. Experiences and perceptions of nurses caring for dying patients and families in the acute medical admission setting. Int J Palliat Nurs, 2013; 19: 423-431.[DOI]

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). This open-access article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Copyright ©

Copyright ©