Assessment and Feedback in Post-pandemic Healthcare Provider Education: A Meta-synthesis

Assessment and Feedback in Post-pandemic Healthcare Provider Education: A Meta-synthesis

Joanne Lusher1*, Isabel Henton1, Samantha Banbury2

1Provost’s Group, Regent’s University London, London, UK

2Psychology Department, London Metropolitan University, London, UK

*Correspondence to: Joanne Lusher, PhD, Professor, Provost’s Group, Regent’s University London, Inner Circle, Regent’s Park, London NW1 4NS, UK; Email: jo.lusher@regents.ac.uk

Abstract

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic has led both to an increased need for and a shortage of trained healthcare staff globally. The population of undergraduate students in health and social care is diverse and widening participation practices are vital to support these students to navigate through academic study. In post-pandemic higher education environments, where hybrid and blended approaches to learning are now more commonplace, research relating to students’ experience, use, perception and understanding of assessment criteria and feedback is ever more important.

Aim: The present review and qualitative thematic meta-synthesis is a secondary analysis following a primary study that aimed to understand students’ understanding of the relationship between assessment criteria and assessment feedback.

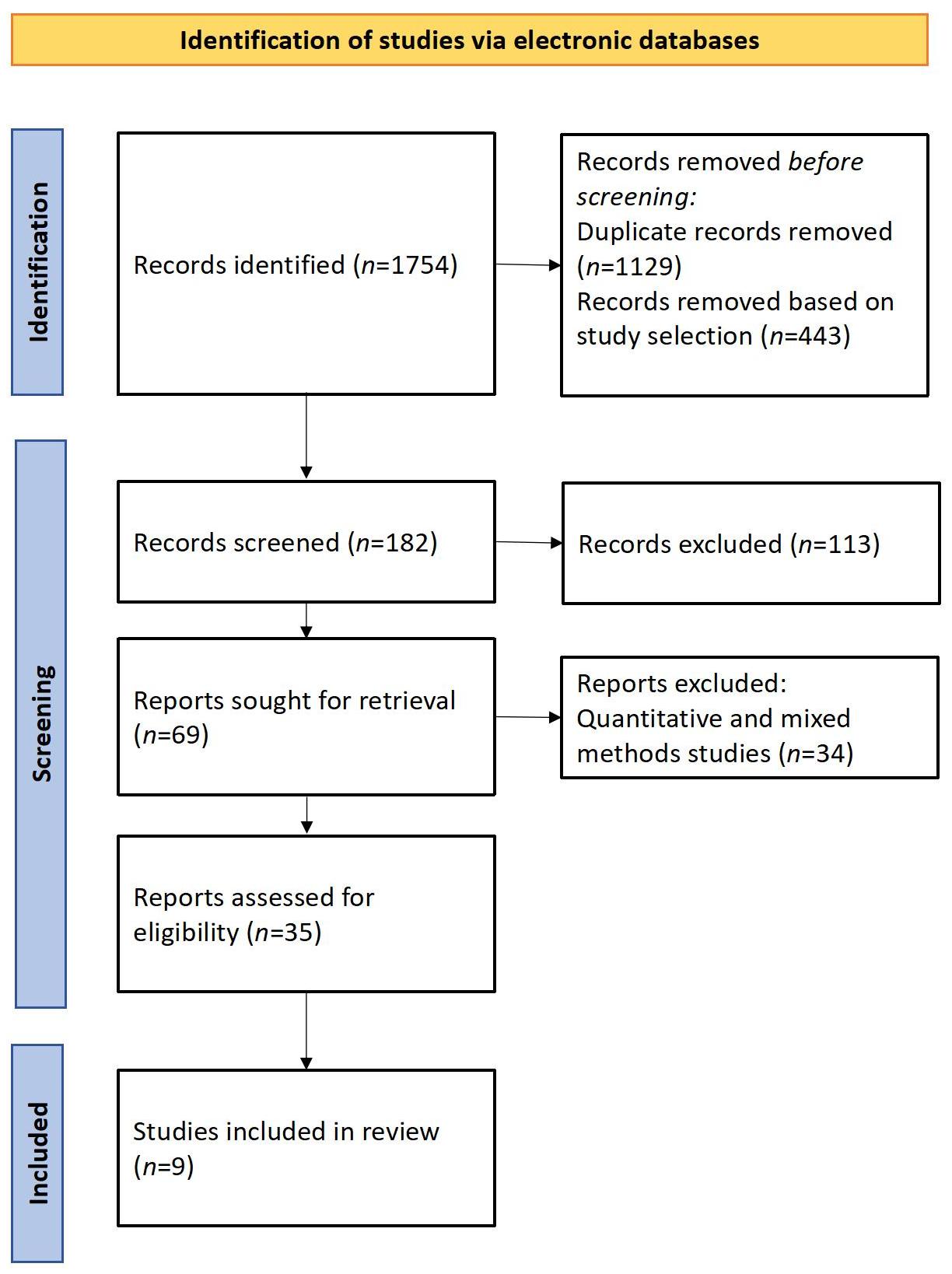

Methods: Using an integrative systematic review method, 1754 articles were initially identified via electronic searches. Study selection was conducted in a series of stages and by agreement between reviewers; 35 articles were selected that met the relevancy criteria. A screening process excluded quantitative and mixed-methods studies, leaving nine qualitative studies for analysis.

Results: Findings highlighted two intersecting themes relating to the importance of “Scaffolding assessment and feedback” and how this linked to students’ “Engagement and perceived self-efficacy”. A constructivist educational framework is proposed to scaffold students’ engagement and perceived self-efficacy in relation to assessment criteria and assessment feedback. Elements in this framework include: (1) multiple modalities for feedback to support inclusive best practice; (2) the provision of mentorship and / or reflective spaces for processing assessment criteria and feedback; and (3) a goal-oriented approach to students’ engagement with assessment criteria and feedback.

Conclusion: Such a framework will make assessment and feedback more transparent and accessible for students, broaden their focus beyond grade attainment, enable them to make links between assessment criteria, assignment writing and assessment feedback, and support inclusivity and staff-student relationships in the context of post-pandemic educational systems.

Keywords: assessment, criteria, feedback, self, efficacy, review, qualitative research

1 INTRODUCTION

Living in a post-pandemic world has increased the need for trained healthcare staff globally[1]. The World Health Organization state that nursing staff are the largest occupational group in the health sector[2]. There is currently a 13 million deficit of nurses employed globally[3]. COVID-19 has changed the way healthcare is delivered worldwide. In this context, there is a need to revisit how students learn and how best to support student nurses and other healthcare providers to achieve their learning outcomes and complete their studies successfully.

Students face a diverse range of challenges when engaging with academic material. Nursing and health and social care studies programs traditionally attract culturally and academically diverse populations of students. Many students enter higher education with limited academic literacy. This can lead to recurrent disappointments with low performance and poor attainment. Widening participation involves considering how best to support students to develop their confidence and independence as they navigate their way through academic study[4]. Students may be helped by the incorporation of real-world challenge-based learning and authentic assessments that are based on real world problem-solving. However, students with poor initial academic skills are more likely to face challenges in engaging with the feedback that they receive from their tutors on their assignments[5].

Moreover, student-tutor interactions and communication about the meaning and purpose of assessment criteria, and how these relate both to learning outcomes and to feedback received have been reported to be effective in promoting academic performance[6]. Indeed, across students, from a range of disciplines, strategies that make assessment criteria more transparent and better linked to learning content tend to be effective in improving academic performance[7]. Constructive as opposed to mechanistic feedback has also reliably been shown to boost academic performance and to encourage more active approaches to learning[8].

Since the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on higher education environments, attention to students’ experience, use, perception and understanding of assessment criteria and assessment feedback remains evermore critically important in higher educational practice. It is particularly important for the diverse population of undergraduate students in nursing and healthcare, where widening participative practices are needed to support their navigation through academic study[4] in the context of lower prior academic attainment and / or perceived self-efficacy.

In post-pandemic higher education environments, where hybrid and blended approaches to learning are now more commonplace, research relating to students’ experience, use, perception and understanding of assessment criteria and feedback is ever more important. This review and qualitative thematic meta-synthesis was therefore carried out to as a secondary study that could complement, update and provide further focus and direction for a primary qualitative study exploring students’ perceptions of using assessment criteria and feedback in their assignment writing, of which the full background has been published elsewhere[9].

The specific objectives of the current review that is reported here were: (1) to explore undergraduate students’ use, experience, perception and understanding of assessment criteria and how these relate to their assessment feedback; and (2) to review and synthesize qualitative studies exploring this topic using a qualitative thematic meta-synthesis approach.

2 METHODS

An integrative review with a qualitative thematic meta-synthesis was conducted based on tried and tested methods[10,11]. Prior to commencement of the review, preliminary searches were conducted in the International Prospective Register of Systemic Reviews and the Cochrane Database for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses, to ensure that no similar systematic reviews were currently underway. The search used the following search terms “assessment” or “assessment criteria” or “feedback” and “undergraduate student”.

2.1 Search Strategy

The search was conducted using the following electronic databases: PsycArticles, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, Science Direct, Web of Science - Core Collection, and Education Resources Information Center Education Source.

The systematic search was operationalized via three components identifying all electronic records containing the terms:

● “Assessment” or “feedback” in the title.

● Related to higher education in the abstract.

● Related to experience, perception, understanding and use in the abstract.

● The reference lists of all included articles were hand searched to identify via a snowballing technique any additional studies; this process did not generate any additional references.

2.2 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Included papers were only those published in the English language and in peer-reviewed journals. To prevent duplication of previous review efforts[12], only papers published from May 2011 to December 2021 were included in the review. Included papers reported the findings of primary qualitative research. Participants in the included studies were undergraduate students (or equivalent) and / or their educators. Study findings needed to relate to students’ experience, use, perception or understanding of assessment criteria and / or assessment feedback. This included the perceptions of educators with regard to their students.

Papers excluded from the review were those:

● Relating exclusively to sources of feedback other than that provided by educators (e.g., peer-to-peer feedback, self-feedback, automated feedback).

● Reporting simply on grade feedback or binary marking of responses (e.g., correct / incorrect).

● Exploring the differential effects of feedback modes (e.g., electronic devices), rather than feedback content.

● Exploring assessment and feedback exclusively relating to practical skills such as clinical skills tests or teacher training.

● Exploring assessment and feedback exclusively on spelling and grammar.

● Investigating assessment and feedback exclusively in the context of learning a foreign language or second language.

● Studies whose participants were not exclusively undergraduates or their educators.

● Studies focusing exclusively on students with neuro-diversities or learning difficulties.

● Grey literature, conference reports or proceedings, abstracts only, and other non-peer reviewed reports.

2.3 Study Selection

As shown in Figure 1, all records (n=1754) identified via electronic searches were exported into a single database file and duplicates were removed. Study selection was then conducted in three stages. Initially, the title of all records minus duplicates were screened and irrelevant records were removed. To ensure accuracy, a second reviewer screened 10% of records by scrutinising the first 112 alphabetically listed references.

|

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

The abstracts of all remaining records were screened against the inclusion / exclusion criteria and records that did not meet the criteria for inclusion were removed. Full texts of all remaining papers were accessed and screened with reasons for exclusion recorded. There was unanimous agreement among reviewers at this stage as to which papers met inclusion criteria and did not need to be excluded of the selection process. These papers were further screened and quantitative or mixed-methods study designs were further excluded. This left nine suitable studies for the qualitative thematic meta-synthesis.

Regarding the eligibility of studies, it was decided that had any disagreements between reviewers occurred, then these were to be managed through face-to-face discussions and if disagreements were not resolved, a third independent reviewer was to be appointed. However, reviewers agreed that the studies included in this review met all inclusion criteria and it was appropriate to exclude all studies that were not included in this review.

2.4 Data Extraction, Evaluation, Synthesis and Audit

Data were extracted, evaluated, synthesized and audited by three independent reviewers using a triangulation approach to the selection of papers in line with inclusion and exclusion criteria, and their subsequent analysis[11]. In line with recommendations[11], the data extracted from each of the nine studies included author(s), country, publication year, aims, methods, sample size, study design, key findings, and any recommendations made by the authors.

Studies were evaluated for their methodological rigor using the Critical Appraisal Skills Program checklist for qualitative studies. The following criteria were evaluated: (1) selection bias; (2) study design confounders; (3) blinding; (4) data collection method; (5) withdrawals and (6) dropouts. In line with the standardized guidance for using these tools, all studies were given a rating of strong, moderate or weak for each criterion, and overall scores were calculated via aggregate ratings for each of the individual components.

It was noted that due to the heterogeneity of the selected studies, shared samples across studies, and wide range of qualitative designs, in line with common meta-review practices, it was not feasible to conduct a pooled meta-analysis of this data and no meaningful outcome from such an analysis. Methods for qualitative thematic synthesis involved three overlapping stages (1) a line-by-line evaluation of the text and development of initial coding; (2) the organization of this coding into descriptive themes; and (3) the development of the final analytic[13].

In the first stage, NVivo software was used to develop codes alongside the reviewers’ independent coding. As each paper was reviewed, codes were compared and synchronized[14]. All codes related to undergraduates’ perspectives on assessment and feedback: some codes for example related to anxiety and feedback; other codes related to misunderstandings of assessment; other codes related to plagiarism; and other codes related to finding feedback useful.

In the second stage, reviewers explored similarities and differences, together with duplication of codes in order to group them into a developing descriptive theme structure[15]. This stage was also influenced by Braun and Clarke[16] thematic analysis method of synthesizing codes across participants into themes by looking for patterns of meaning across the whole.

This method became the main guiding tool in the third stage, when analytic themes were generated from reviewing and re-reviewing the initial codes and the initial themes. The whole analysis process was carried out both independently by each researcher with successive triangulation processes to ensure consistent and agreed upon outcomes. Each researcher used a reflexive journal to explore their own reflective and reflexive material during the process. In particular, the researchers noted any biases that emerged in their analysis at each stage. This reflective work formed a basis for revisiting the analysis to ensure it remained thoroughly grounded in participants’ data[15].

3 RESULTS

These qualitative findings are based on analysis conducted across nine qualitative studies that are summarized in Table 1[17-25]. Findings are organized into the following two overarching themes: “Scaffolding assessment and feedback” and “Engagement and perceived self-efficacy”.

Table 1. Summary of Papers Included in This Review

Study (Year) |

Aims |

Methods |

Key Findings and Recommendations |

Douglas et al.[17] (2019) |

To better understand the student experience through discourse. |

Theoretical approach drawing from data collected using story completion methods and semi-structured interviews with students. |

Theorizes transitioning as troublesome and rhizomatic. Suggests that this approach might offer potential for looking beyond normative narrative and recommends celebrating students’ becoming in a generative and rich and generative manner. |

Hepplestone and Chikwa[18] (2014) |

To explore the subconscious processes that students use to engage with feedback. |

Qualitative study conducted with a group of under-graduates who were tasked with reflecting on the approach and processes they adopt when engaging with, acting upon, storing and recalling feedback. The study usedmicro-blogging; a weekly diary, as well as semi-structured interviews. |

Undergraduates recognize the influence and use of technology in enhancing feedback process, particularly when it comes to supporting discussions around feedback. Students, however, do find it challenging to see the connections between feedback received from tutors and writing future assignments. Further investigation is required into the role that technology has in enabling students to make better sense of the feedback they receive from their tutors. |

Killingback et al.[19] (2020) |

To explore experiences and choices of preferred feedback of both students and tutors. |

Convenience sample of 25 undergraduates who were recruited for 3 focus group sessions. 5 tutors took part in semi-structured interviews. One-to-one interviews and focus groups were carried out using a semi-structured interview schedule. Data were then analyzed using an inductive thematic analysis approach. |

3 key themes were identified that illustrated there was a level of importance placed on human connection and additional benefit could be received though nonverbal communication methods. 2 themes emerged from the tutors’ perspective and these also focused on feedback preferences. Tutors voiced their experiences of challenges surrounding offering verbal feedback, as well as the importance attached to self-assessment. Key challenges identified in this study surrounded selecting optimal feedback styles in relation to the absence or limits of any clear student-tutor consensus. Students preferred lecturer-led methods that viewed as offering the greatest level of quality personal interaction with tutors (including use of audio, video, face-to-face and screencast methods). Whereas tutors tended to advocate student-led feedback approaches, such as peer- or self- assessment. |

Leong and Lee[20] (2018) |

To investigate the views of students and tutors on tutor feedback practices and student assignment writing. |

8 undergraduate students and 9 tutors took part in focus groups. Discussions included topics on specific areas that both groups thought feedback should cover, as well as purposes of assessment feedback. |

Students voiced views around the belief that feedback should be more detailed, and that students’ needs were not always being met. Proposed recommendations included the argument to create more dialogic environments between students and their tutors that could facilitate provision for more personalized feedback on assessments and assignment writing. |

Orsmond and Merry[21] (2012) |

To further understand how students process tutor feedback. |

The study employed 36 final year undergraduates from 4 universities. Focus groups and interviews were used to collect data that were then analyzed using a thematic analysis approach. |

Overall, the study identified major differences in how students process assessment feedback. There are 3 key areas involved, including self-assessment methods, external regulation techniques and peer-support. Recommendations included guiding students on their use of tutor feedback that is designed in such a way as to encourage students to further develop their self-assessment skills and practices. |

Pazio[22] (2016) |

To identify points of conflict between student experiences of assessment feedback and tutor perceptions of their own feedback practices. |

12 interviews were conducted with tutors along with the collection of student data that was obtained through questionnaires and focus groups. |

Identified common themes where there were discrepancies between students’ and tutors’ accounts affecting satisfaction with feedback on assignments. Students require further clarity regarding purpose and standards. Establishing a dialogue between students and their tutors would be considered one way in which to improve the use of assessment feedback. |

Pitt and Norton[23] (2017) |

To further understand why feedback is not always acted upon. |

In-depth interviews with 14 undergraduate students who were required to reflect on their perceptions of receiving written feedback on graded work. Students were also asked to reflect on examples of what they perceived as being good and poor work. |

Key outcomes were that emotional reaction plays a crucial part in determining how feedback is received by students and how they use the feedback received. The paper introduces this emotional backwash as a concept that could be considered in future research. |

Winstone and Boud[24] (2016) |

To explore the relationship between students’ expectations of feedback. |

Activity orientated focus group sessions were employed to explore psychology students’ perceptions and experiences of feedback. |

Study found a mismatch between the expectations of students and tutors in relation to the level of autonomy. Students demonstrated conflicting perspectives whereby they desired autonomy but at the same time wanted a sense of security that can be achieved through a more dependent learning approach. Recommendation for future research included the consideration that undergraduate students are passing through a key period of transition during their first year at university so during this time, students are simultaneously attempting to leave one identity behind as they gradually transition into their new identity as autonomous learners. |

García-Sanpedro[25] (2020) |

To explore the perspectives of both students and tutors on the use of assessment feedback and grades, and the practice strategies that are used to improve students’ academic potential. |

The study used a case study approach using a symbolic interpretative paradigm on 12 undergraduate courses. |

Main findings reported that students’ use of feedback is not always generalized and tends to be used primarily for the purposes of informing the assignment grade. Recommendations are to incorporate feed-back and feed-forward methods in teaching practice more systematically whilst offering more guidance that directs students towards ways in which they can improve their academic performance. |

3.1 Scaffolding Assessment and Feedback

It was evident that students’ primary focus was on grades as a measure of their academic performance. Whilst students considered positive feedback useful, positive feedback that was not reflected in students’ grade was also experienced negatively. Some authors suggested that students with higher grades were less likely to engage in their feedback compared to those with lower grades, which is suggestive of the priority focus students have on grades[20].

Students appeared more interested in negative feedback when it included recommendations for how to improve their assessment grade in the future[25]. Scaffolding activity such as feedforward as to how to improve assessment grades was reported to be helpful in building students’ understanding of the assessment criteria, and in developing their perceived self-efficacy towards more complex problem-solving in the future. For some students, negative feedback acted as a motivator; however, for others it was experienced as demotivating, reducing their academic engagement, and with a negative effect on their academic performance[19].

There was some evidence of concerns about the consistency of marking standards and feedback from staff, both in terms of the content and volume of feedback[24]. However, one of the biggest concerns voiced by students was when the feedback was vague, that is, when it did not refer to how they might improve their work. Students found clarity and specificity about what needed to change, examples of best practice, recommendations in context, and feedforward all to be supportive in feedback[25]. Students also voiced a need for specificity in terms of prior instructions on what was wanted in the assessment, together with expectations of content and how this was mapped to the grading system.

Overall, the focus on grades seems to imply reductionist or perhaps even consumer attitudes among students towards feedback, only valuing feedback that led to higher grades. However, the more constructive finding within this theme relates to the importance of scaffolding students in relation to assessment criteria and feedback, for example informing students about the complex nature of marking and why perceived inconsistencies might have valid reasons behind them.

3.2 Engagement and Perceived Self-efficacy

This theme reflects how students’ concerns, about assessment guidance, and the quality and consistency of feedback[17,24], compromises their engagement with assessment and feedback[22]. Additionally, the theme explores how students perceived self-efficacy impacts their engagement with feedback. Perceived self-efficacy was reflected in students’ ability to ask for support to better understand their feedback, and to attend to their feedback in a proactive and goal-setting way[26]. Students with lower perceived self-efficacy were more likely to disengage with their feedback, compared to those with higher levels of self-efficacy. This included students who understood their feedback but did not act upon it.

This theme circles back to the first theme in so far as it suggests the need for scaffolding, not only to support students to understand the nature and content of their feedback, but also to support them in developing their sense of their own ability to learn in a self-directed way[21]. In the context of scaffolding to support engagement and perceived self-efficacy, students preferred to have a dialogue with their assessors. The approachability and attitudes of assessors were identified as an important influence on engagement and perceived self-efficacy. Students perceived continued communication and engagement with their feedback via varied mediums including dialogue as helpful in meeting their needs.

However, linking back to the first theme, the need for continued and dialogical scaffolding tended to predominate among those students with lower grades compared to those who had achieved higher grades, who were more likely to hold the belief that they did not need to engage in further communication or dialogue. In this context, the assessor’s attitude, and availability to scaffold feedback with higher-performing students is also of relevance; it may be as important to proactively seek out students with higher ability who are less likely to take up opportunities for feedback meetings.

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Scaffolding Assessment and Feedback

The main themes yielded from this systematic review and qualitative thematic meta-synthesis were “Scaffolding assessment and feedback” and “Engagement and perceived self-efficacy”. With reference to scaffolding assessment and feedback, effective written feedback involves clarity and specificity in terms of what is needed to improve future assignments.

Gibbs[27] argues against using high volumes of written feedback as this is seldom meaningful to students and tends to involve or generate a lack clarity as to what is needed to improve. Timing is also a key factor in best practice on feedback and needs to be in keeping with the developmental approach towards learning competencies relating to practice that is being taken on the course more generally[27].

In order to improve scaffolding in assessment and feedback processes, formative assessments tend to be an excellent way to assess students’ progress. Formative assessments can often be constituted of feedback on a students’ drafts for their summative assessment. Formative feedback builds students’ skills and understanding of the assessment process[28]. Inclusive approaches to assessment, such as modifying assessment strategies (and teaching methods and content) to accommodate diverse students’ needs are also likely to be helpful in supporting and scaffolding engagement and self-efficacy among students.

4.2 Engagement and Perceived Self-efficacy

It is widely accepted that students’ active participation in the learning process supports their learning, engagement, and perceived self-efficacy. The provision of academic mentors, advisors, or coaches at an institutional level (beyond the module leader or tutor) can be an additional human resource to scaffold formative and feedforward approaches to learning for students and can support and strengthen students’ voices in the assessment and feedback process[29].

Similarly, the use of supportive feedback groups can support engagement and perceived self-efficacy in a less pressured environment outside the context of particular assignments. Such groups may involve reflective practices and skills improvisation to explore feedback in a focused, developmental and efficacy-oriented manner[17]. This might prove useful especially for undergraduate health or nursing students where it has been suggested that reflecting on practice and on feedback can support the development of perceived self-efficacy. These dialogical approaches to learning and development may also support constructive interactions between students and staff, by providing an explicit additional platform to support students’ access to tutors.

Finally, alternative feedback modes such as podcast, video, audio and screencast may also enhance the tutor-student relationship and in turn students’ feedback experience and engagement, as well as promote inclusive feedback practices[30]. It is noted however, that students’ varying degrees of engagement with assessment criteria and feedback may go beyond how assessment criteria and feedback are presented and used. Research suggests that students’ engagement with feedback can fluctuate throughout the undergraduate degree[31]. Whilst engagement is similar for first- and second-year undergraduate students, it appears that engagement with feedback can be at its lowest in the final year[31].

4.3 COVID-19 Factors

It is noted that the studies included in this review may not be fully representative of the recent pandemic era. These findings should be considered provisional and should be reviewed in the context of the newly emerging blended and hybrid learning environments in higher education since the pandemic. Many universities are now incorporating hybrid or blended learning practices and relying, to a further degree, on digital or e-learning methods and approaches to assessment and feedback[31]. Linked to these developments are social and culturally changing demographics in higher education and the increased globalization of higher education. Both of these factors are likely to continue to impact how educators teach, assess and feed back to students[31].

In a large survey of 37,720 students in higher education settings prior to the pandemic, 80% of students accessed recorded lectures once per week, and 70% utilized digital tools for accessing additional resources[32]. Overall, student satisfaction with using technology in support of learning in HE was high (88%)[33]. The increased use of varied e-environments (Virtual Learning Environments, medial, discussion boards, videoconferencing software) since the pandemic may systematize the actions of students, which will provide directions for educators to act upon[34]. Accessing the student voice and feedback on the use of virtual learning environments supports bottom-up approaches to decision-making in education, as well as students’ sense of inclusion and belongingness in online or hybrid environments[34] particularly in the context of diverse student populations[35] such as those in health and nursing contexts. Staff-student collaborative spaces becomes even more necessary in the context of hybrid and blended learning practices, to effectively address the learning and personal development needs of students[36], including their ability to engage with and perceived self-efficacy in relation to assessment criteria and assessment feedback.

4.4 Online and Distance Learning Factors

Like all educational sectors, COVID-19 impacted nursing education in the way the curriculum was delivered and received by students[37]. Whilst e-learning had been utilized prior to the pandemic in the nursing profession, COVID-19 restrictions resulted in a heavier reliance on virtual learning environments. In a pre-pandemic study[37] it was suggested that break out rooms, videos, quizzes, and other virtual means were all helpful to develop a sense of connectedness. Universities that utilized a blended learning approach prior to the pandemic, yielded more favorable resilience outcomes than universities less geared towards blended teaching and learning approaches[38].

A meta-analysis found that online teaching increased subject knowledge among medical students[39]. This may be due to having an opportunity to review for example pre-recorded lectures and materials. One issue reported was distraction among students when using e-learning environments and those teaching nursing students have been urged to engage students using blended learning approaches to minimize this[40]. Students reported feeling pressured to keep up with the content and experiencing challenges with the self-regulatory behavior necessary for content engagement. In this context, self-regulation related to autonomy, self-motivation, and efficacy in setting goals[41]. One way to mitigate this proved to be the incorporation of varied teaching tools and strategies to retain interest and focus. Goal setting might also support students' motivation and reduce procrastination[42].

However, there are some further considerations that are particular to the health sector. Healthcare provider education necessarily involves both knowledge and skills development, including the development of reflective skills[43]. It has been argued that the acquisition of the relevant knowledge and skills can be facilitated or hindered by internal factors such as beliefs, values, and attitudes, along with external factors such as societal and environmental conditions[43]. Clearly the pandemic involved a rapid and significant change in the societal and environmental conditions for learning, which was likely to have had a powerful impact on students’ perceived self-efficacy, confidence, wellbeing and health. Students faced a rapid transition from face-to-face to e-learning requiring them to embrace new knowledge and to change their behavior to support this transition. Nursing lecturers also had to transition to an e-learning environment, with limited time to conceptualize teaching and learning practices. A large cross-sectional study[44] explored Taiwanese nursing students’ perspectives of online teaching and whether changes in teaching models affected their intention to join the nursing workforce, which might be considered a facet of perceived-self-efficacy. The majority of students (78.6%) found online approaches to teaching more flexible than in-person delivery. However, relevant to the present study, up to 64.8% of participants considered that their online courses had negatively impacted their preparations for future nursing jobs, Specific factors included a lack of proficiency in nursing skills, and inadequate actual interactions with patients.

Indeed, at the time this current review was first conceived, many academic health programs were forced to cease clinical placements for nursing students. Limitations in terms of face-to-face and one-on-one student-to-patient training clearly posed significant challenges on all learning[45]. Consequently, e-learning environments were created to continue supporting students. Public and population health educators were forced to teach students to work with patients on the basis of understanding the needs of a population rather than interacting with the needs of the individual. One particular study found that practicing what has been learned in the classroom at home, using a volunteer for physical examination, resulted in increased self-efficacy[45]. However, further thinking is required in terms of a strategy for the teaching and assessment of clinical skills in future online nursing education[46]. A further study[47] with over 800 Polish medical students, similarly, found that online learning was perceived to have advantages and disadvantages for students. Advantages included the ability to stay at home; constant access to online materials, learning at own pace; and in comfortable surroundings. However, the main disadvantage was the lack of real-world interactions with patients. Technical issues with IT were the second main disadvantage. Although there was no statistical difference between face-to-face and online learning to deliver knowledge, e-learning was significantly less effective in delivering skills and social competencies. These authors argued that the findings imply the need for a considered strategy and a more pro-active approach to skills learning in the context of online delivery[47]. Similarly, nursing students report that online clinical training is too abstract when compared with real-world training; it was left to the subjective imagination of the student to develop their clinical skills[44]. A previous systematic review[48] exploring the potential for online / blended learning to teach clinical skills in undergraduate learning, found that online teaching of clinical skills was no less effective than in-person approaches. Further studies have argued that clinical practice training cannot be completely replaced with online teaching[49] and that emotional support is key to support students in overcoming stressful emotions during crisis situations[50]. Taken together these studies offer support in recognizing the importance of engagement and contact with tutors in the context of assimilating assessment and feedback.

4.5 Recommendations for Future Practice of Assessment and Feedback in A Post-pandemic Era

In support of a recommendation around engagement and perceived self-efficacy, a study among Iranian nursing students found that online interactions and engagement between students and staff became hindered and problematic, leaving students feeling isolated and non-engaged[51]. Others[52] have argued that the level of interaction between students and staff is critical in maintaining subject interest and this level of interaction need not be lost outside of the face-to-face in-person classroom. These factors suggest that enhanced interaction could be established via focusing on rapport and increasing dialogue between students and students and educators whether verbally or in online chats during the lecture. Live stream approaches over asynchronous teaching have also been suggested to retain student attention.

A lack of contact with peers and faculty staff can lead to increased levels of depression and anxiety among students[53]. The transition to learning remotely may have induced anxiety during the pandemic, particularly due to the uncertainty of how long the pandemic would continue and therefore the impact it would have on their future career pathways. Prior to the pandemic, nursing students already reported higher levels of anxiety than other university students[54]. Heightened levels of stress can be linked to compromised perceived self-efficacy and motivation, and decreased performance[55].

Within an academic context, resilience relates to students’ ability to sustain high levels of motivation and academic performance, despite the presence of stressful events and conditions[56]. Heightened levels of perceived self-efficacy, confidence, feelings of being in control and perseverance are all positively associated with positive academic experiences.

Based on the current findings of this review, the focal recommendations arising revolves around the adoption of a constructivist educational framework to scaffold students in relation to assessment criteria and feedback. For example, we support suggestions that educators should provide a range of modalities, including online forms of support and feedback, to support inclusive educational practice: these may include video, podcast, audio and screencast, as just a few examples[19,29].

Additionally, dialogical spaces, such as academic mentorship, advisory and / or reflective spaces with educators in which students can interact, communicate, listen, discuss new ideas, and develop new concepts to support their engagement with assessment criteria and feedback are important[30]. These sorts of spaces may help to scaffold not only the content of assessment criteria and assessment feedback, but students’ increased understanding of the nature and rationale of assessment and feedback practices, to support increased transparency. They may also broaden students’ focus away from a more consumerist or reductionist focus solely on grade attainment. They may also attract more able students to engage with learning and pedagogy around assessment and feedback more at depth, especially if these activities are not tied to the attainment of particular assignments[20]. Such spaces can be co-designed with students in line with a developmental approach to supporting students at different stages in their journey of academic and competency-based learning[27].

These spaces can enhance a sense of belongingness in the context of online or hybrid learning higher education environments. In these environments, it may be more likely that students experience stress or low mood due to a greater degree of isolation, which in turn mediate or moderate their capacity to engage with assessment criteria and feedback. Further qualitative research might investigate students’ experiences and perceptions of belongingness in the context of online or hybrid learning environments in nursing or health and social care higher educational contexts to further support these directions.

Finally, to better support formative and feedforward assessment and feedback processes, and in the context of additional spaces to scaffold students’ engagement with assessment criteria and feedback, it may also be helpful to consider a goal-oriented approach, in which students are set holistic goals in relation to improving assessment work and through which their improvements might be jointly engaged with and monitored. Again, this approach might support students to broaden and deepen their focus beyond grade attainment, through the construction of non-grade-related learning and assessment goals. A goal-oriented approach seems likely to help make learning processes more transparent and accessible to students so they can make vital links between assessment criteria, assignment writing and assessment feedback. It would be important in setting goals for there to be clear indicators, for example SMART goals, and for goals to be conceptualized and languaged in such a way as to support inclusivity[57]. For instance, positive goals could be oriented around an explorations of students’ own history and values, perhaps using concepts and language, relating to worth, esteem, support, respect, and care.

5. CONCLUSION

Both prior to and since the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on higher education environments, attention to students’ experience, use, perception and understanding of assessment criteria and assessment feedback remains critically important in higher educational practice. It is particularly important for the diverse population of undergraduate students in health and social care, where widening participative practices are needed to support their navigation through academic study in the context of lower prior academic attainment and / or perceived self-efficacy. It is important for educational practices to be motivational, to sustain progression and the attainment of these students’ practice-based and academic goals. These issues have also been amplified by the increased need for trained healthcare staff globally since the pandemic. The prevalence of nursing staff as an occupational group and the shortage of nurses globally makes attending to effective higher education practices in healthcare and nursing of increased importance. Given these contexts, this review and qualitative thematic meta-synthesis has explored how students receive and use assessment criteria and feedback in order to inform future best practice in healthcare provider education in the post-pandemic era.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Author Contribution

Lusher J was responsible for conceptualization, methodology, writing-original draft preparation, project administration and funding acquisition. Henton I and Banbury S were responsible for validation. Banbury S was responsible for formal analysis and data curation. Lusher J, Henton I, Banbury S were responsible for writing-review and editing. All authors contributed to the manuscript and approved the final version.

References

[1] Tanaka N, Miyamoto K. The world needs more and better nurses. Here’s how the education sector can help. Education for Global Development. Accessed 20 November 2022. Available at: https://blogs.worldbank.org/education/world-needs-more-and-better-nurses-heres-how-education-sector-can-help

[2] The world health organization. State of the world’s nursing 2020: Investing in education, jobs and leadership. Accessed 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003279

[3] ICN. International Council of Nurses Policy Brief: The global nursing shortage and nurse retention. Accessed 6 November 2022. Available at: https://www.icn.ch/sites/default/files/inline-files/ICN%20Policy%20Brief_Nurse%20Shortage%20and%20Retention_0.pdf

[4] Norton L, Harrington K, Elander J et al. Supporting students to improve their essay writing through assessment criteria focused workshops. Oxford: Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development, 2005.

[5] Pitt E, Bearman M, Estherhazy R. The conundrum of low achievement and feedback for learning. Assess Eval High Educ, 2019; 45: 239-250. DOI: 10.1080/02602938.2019.1630363

[6] Lusher J. How small-group teaching can be used to improve performance in student assessment. Health Psychol, 2007; 16: 34-38. DOI: 10.53841/bpshpu.2007.16.1-2.34

[7] Harrington K, Norton L, Elander J et al. Using core assessment criteria to improve essay writing. London: Taylor and Francis Group, 2006.

[8] Boud D, Molloy E. Rethinking models of feedback for learning: The challenge of design. Assess Eval High Educ, 2012; 38: 698-712. DOI: 10.1080/02602938.2012.691462

[9] Lusher J, Clements H, Stevens E. A qualitative insight into time-poor / grade-hungry students’ perceptions of using assessment criteria and feedback in assignment writing. Nurs Educ Today, 2021; 104: 104999. DOI: 10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104999

[10] Watty K, Lange P, Carr R et al. Accounting students’ feedback on feedback in australian universities: They’re less than impressed. Account Educ, 2013; 22: 467-488. DOI: 10.1080/09639284.2013.823746

[11] Finfgeld-Connett D. A guide to qualitative meta-synthesis. Taylor & Francis Group: New York, USA, 2018. DOI: 10.4324/9781351212793

[12] Esterhazy R, Nerland M, Damşa C. Designing for productive feedback: An analysis of two undergraduate courses in biology and engineering. Teach High Educ, 2019; 26: 806-822. DOI: 10.1080/13562517.2019.1686699

[13] Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol, 2008; 8: 45. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

[14] Britten N, Campbell R, Pope C et al. Using meta ethnography to synthesize qualitative research: A worked example. J Health Serv Res Po, 2002; 7: 209-215. DOI: 10.1258/135581902320432732

[15] Bonanno GA. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely adverse events? Am Psychol, 2004; 59: 20-28. DOI: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20

[16] Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol, 2006; 3: 77-101. DOI: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

[17] Douglas T, Salter S, Iglesias M et al. The feedback process: Perspectives of first- and second-year undergraduate students in the disciplines of education, health science and nursing. J Univ Teach Learn P, 2016; 13. DOI: 10.53761/1.13.1.3

[18] Hepplestone S, Chikwa G. Understanding how students process and use feedback to support their learning. Pract Res High Educ, 2014; 8: 41-53.

[19] Killingback C, Drury D, Mahato P et al. Student feedback delivery modes: A qualitative study of student and lecturer views. Nurs Educ Today, 2020; 84. DOI: 10.1016/j.nedt.2019.104237

[20] Leong AP, Lee HH. From both sides of the classroom: perspectives on teacher feedback on academic writing and feedback practice. J Teach Engl Specific, 2018; 6: 151-164. DOI: 10.22190/JTESAP1801151L

[21] Orsmond P, Merry S. The importance of self-assessment in students’ use of tutors’ feedback: A qualitative study of high and non-high achieving biology undergraduates. Assess Eval High Educ, 2012; 38, 737-753. DOI: 10.1080/02602938.2012.697868

[22] Pazio M. The discrepancies between staff and students' perceptions of feedback and assessment practices - analysis of TESTA data from one HE institution. Pract Res High Educ, 2016; 10: 91-108.

[23] Pitt E, Norton L. ‘Now that’s the feedback I want!’ Students’ reactions to feedback on graded work and what they do with it. Assess Eval High Educ, 2017; 42: 499-516. DOI: 10.1080/02602938.2016.1142500

[24] Winstone NE, Boud D. The need to disentangle assessment and feedback in higher education. Stud High Educ, 2020; 47: 656-667. DOI: 10.1080/03075079.2020.1779687

[25] García-Sanpedro MJ. Feedback and feedforward: Focal points for improving academic performance. J Technol Sci Educ, 2012; 2: 77-85. DOI: 10.3926/jotse.49

[26] Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: WH Freeman and Company, 1997: 37-78.

[27] Gibbs G. Using assessment to support student learning. Leeds Met Press, 2010.

[28] Doe C. Student Interpretations of Diagnostic Feedback. Lang Assess Q, 2015; 12, 110-135. DOI: 10.1080/15434303.2014.1002925

[29] Price M, Handley K, Millar J. Feedback: Focusing attention on engagement. Stud High Educ, 2011; 36: 879-896. DOI: 10.1080/03075079.2010.483513

[30] Chardon T, Collins P, Hammer S et al. Criterion referenced assessment as a form of feedback: Student and staff perceptions in the initial stages of a new law degree. Inter J Pedagog Learn, 2011; 6, 232-242. DOI: 10.5172/ijpl.2011.6.3.232

[31] Ali N, Ahmed L, Rose S. Identifying predictors of students’ perception of and engagement with assessment feedback. Act Learn High Educ, 2018; 19: 239-251. DOI: 10.1177/1469787417735609

[32] Newman T, Beetham H. Student digital experience tracker 2017: The voice of 22,000 UK learners. Bristol: Jisc, 2017.

[33] Burkhanova FB, Rodionova SE. Implementing innovative active and interactive methods of learning and educational technology in Russian colleges: Current state and emerging issues. Bulletin of the Bashkir University, 2012; 4: 1862-1875.

[34] Inko-Tariah C. Improving through inclusion: Supporting black and minority staff networks in the NHS part two. NHS England, 2018.

[35] Abdullah Z, Banbury S, Visick A et al. The role of religiosity in depression and anxiety among muslim students in the UK: A whole-person approach to teaching and learning. J Islam Stud, 2021; 6: 84-101. DOI: 10.2979/jims.6.1.04

[36] Blair A, Curtis S, Goodwin M et al. What feedback do students want? Politics-Oxford, 2013; 33: 66-79. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9256.2012.01446.x

[37] Small F, Attree K. Undergraduate student responses to feedback: Expectations and experiences. Stud High Educ, 2016; 41: 2078-2094. DOI: 10.1080/03075079.2015.1007944

[38] Reilly JR, Gallagher‐Lepak S, Killion C. “Me and my computer”: Emotional factors in online learning. Nurs Educ Perspect, 2012; 33: 100‐105. DOI: 10.5480/1536-5026-33.2.100

[39] Kyaw BM, Posadzki P, Dunleavy G et al. Offline digital education for medical students: Systematic review and meta-analysis by the digital health education collaboration. J Med Internet Res, 2019; 21: e13165. DOI: 10.2196/13165

[40] Muir S, Tirlea L, Elphinstone B et al. Promoting classroom engagement through the use of an online student response system: A mixed methods analysis. J Stat Educ, 2020; 28: 25-31. DOI: 10.1080/10691898.2020.1730733

[41] Pazio M. The Discrepancies between Staff and Students’ Perceptions of Feedback and Assessment Practices - Analysis of TESTA Data from One HE Institution. Pract Res High Educ, 2016; 10: 91-108.

[42] Peixoto EM, Pallini AC, Vallerand RJ et al. The role of passion for studies on academic procrastination and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc Psychol Educ, 2021; 24: 877-893. DOI: 10.1007/s11218-021-09636-9

[43] Meleis AI, Sawyer LM, Im E et al. Experiencing transitions: An emerging middle‐range theory. Adv Nurs Sci, 2000; 23: 12‐28. DOI: 10.1097/00012272-200009000-00006

[44] Hsu PT, Ho YF. Effects of online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic on nursing students’ intention to join the nursing workforce: A cross-sectional study. Healthcare-Basel, 2022; 10: 1461. DOI: 10.3390/healthcare10081461

[45] Yancey NR. Disrupting rhythms: Nurse education and a pandemic. Nurs Sci Quart, 2020; 33: 4. DOI: 10.1177/0894318420946493

[46] Konrad S, Fitzgerald A, Deckers C. Nursing fundamentals-supporting clinical competency online during the COVID-19 pandemic. Teach Learn Nurs, 2021; 16: 53-56. DOI: 10.1016/j.teln.2020.07.005

[47] Bączek M, Zagańczyk-Bączek M, Szpringer M et al. Students’ perception of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: A survey study of Polish medical students. Medicine, 2021; 100: e24821. DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000024821

[48] McCutcheon K, Lohan M, Traynor M et al. A systematic review evaluating the impact of online or blended learning vs. face‐to‐face learning of clinical skills in undergraduate nurse education. J Adv Nurs, 2015; 71: 255-270. DOI: 10.1111/jan.12509

[49] McDonald EW, Boulton JL, Davis JL. E-learning and nursing assessment skills and knowledge-An integrative review. Nurs Educ Today, 2018; 66: 166-174. DOI: 10.1016/j.nedt.2018.03.011

[50] Casafont C, Fabrellas N, Rivera P et al. Experiences of nursing students as healthcare aid during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: A phenomenological research study. Nurs Educ Today, 2021; 97: 104711. DOI: 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104711

[51] Salmani N, Bagheri I, Dadgari A. Iranian nursing students’ experiences regarding the status of e-learning during COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One, 2022; 17: e0263388. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0263388

[52] Cantey DS, Sampson M, Vaughn J et al. Skills, community, and rapport: Prelicensure nursing students in the virtual learning environment. Teach Learn Nurs, 2021; 16: 384-388. DOI: 10.1016/j.teln.2021.05.010

[53] Rosenthal L, Lee S, Jenkins P et al. A survey of mental health in graduate nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurs Educ, 2021; 46: 215-220. DOI: 10.1097/NNE.0000000000001013

[54] Bartlett ML, Taylor H, Nelson JD. Comparison of mental health characteristics and stress between baccalaureate nursing students and non‐nursing students. J Nurs Educ, 2016; 55: 87‐90. DOI: 10.3928/01484834-20160114-05

[55] Reeve KL, Shumaker CJ, Yearwood EL et al. Perceived stress and social support in undergraduate nursing students’ educational experiences. Nurs Educ Today, 2013; 33: 419‐424. DOI: 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.11.009

[56] Wang MC, Gordon EW. Educational resilience in inner-city America: Challenges and prospects. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2012.

[57] Austen L, Malone C. What students’ want in written feedback: Praise, clarity, and precise individual commentary. Pract Res High Educ, 2018; 11: 47-58.

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). This open-access article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Copyright ©

Copyright ©