"Virtual Parallel Societies"—A Study on the Differences in Mobile Application Usage Between Hong Kong and Mainland Chinese Adolescents

Yik Wong Tseung1*, Binyu Xie2, Ziting Peng1

1 School of Economics, Guangzhou College of Commerce.

2 School of Arts, Guangzhou College of Commerce.

*Correspondence to: Yik Wong Tseung, PhD, Associate Professor, School of Economics, Guangzhou College of Commerce, 222 Kowloon Avenue, Longhu Street, Guangzhou, 511363, Guangdong Province, China; Email: tseung@163.com.

Abstract

Objective: This study explores the differences in mobile application usage between adolescents in Hong Kong and Mainland China, highlighting how these variances contribute to the formation of virtual parallel societies.

Methods: The theoretical framework incorporates Walter Lippmann's Public Opinion and Eli Pariser's Filter Bubbles to explain how algorithm-driven platforms foster informational silos. The study employed a mixed-methods approach, primarily using secondary data from the QuestMobile 2023 China Mobile Internet Annual Report and data from the Department of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, along with qualitative research methods such as semi-structured interviews and content analysis of social media interactions.

Results: The findings suggest significant disparities in app usage between adolescents in Hong Kong and Mainland China, influenced by technological, sociological, and political factors. Adolescents in Hong Kong preferred global platforms like Instagram and Facebook, while Mainland Chinese adolescents used local platforms like WeChat and Weibo. These differences were influenced by sociological factors, including class, education, and access to technology, and contributed to the formation of distinct informational silos.

Conclusion: The differences in mobile application usage have led to the development of virtual parallel societies, with implications for national identity and socio-political cohesion. Policy recommendations include enhancing media literacy, promoting Chinese perspectives globally, and encouraging social media platforms that foster a shared national identity.

Keywords: mobile application usage, adolescents, virtual societies, national identity

1 INTRODUCTION

The rapid proliferation of mobile applications has significantly transformed the way adolescents engage with information, communicate, and form identities. In regions with complex socio-political dynamics, such as Hong Kong and Mainland China, these digital engagements can lead to the development of distinct virtual societies. This study aims to investigate the differences in mobile application usage between adolescents in Hong Kong and Mainland China, exploring how these differences contribute to the formation of virtual parallel societies[1]. The theoretical framework draws upon Walter Lippmann's concept of Public Opinion and Eli Pariser's Filter Bubbles to elucidate the mechanisms through which algorithm-driven platforms create informational silos, thereby fostering divergent social realities.

This study employed a mixed-methods approach, primarily using secondary data from the QuestMobile 2023 China Mobile Internet Annual Report and data from the Department of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, along with qualitative research methods. In addition to statistical analysis, qualitative data was gathered through semi-structured interviews with 12 participants from each region to gain insights into their motivations and attitudes towards mobile app usage. Content analysis of social media interactions was also conducted to understand the broader digital discourse. The theoretical framework of technological determinism and platform studies was applied to analyze the impact of platform architecture on user behavior.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Usage Background

2.1.1 Increased Dependence on Mobile Internet

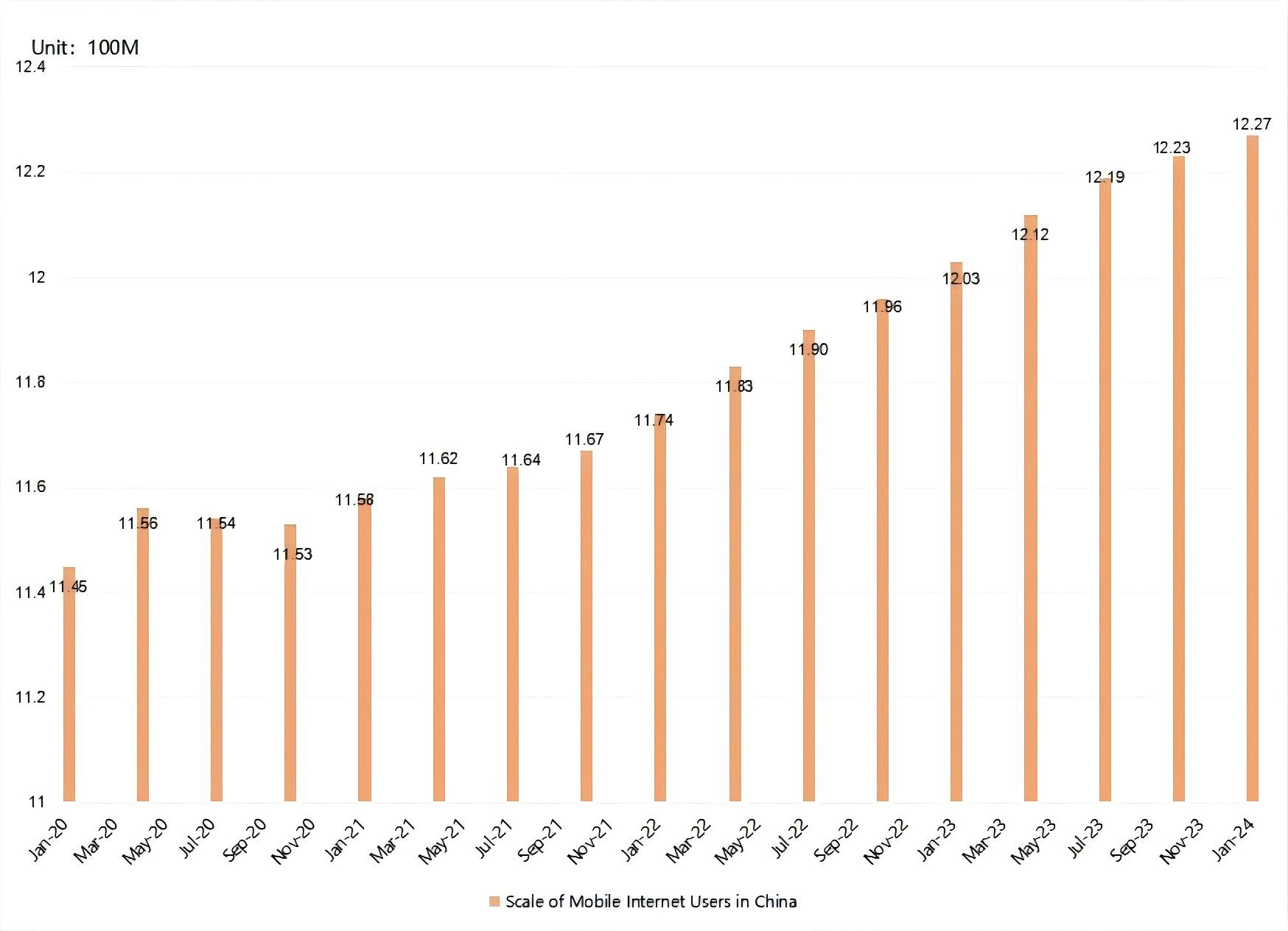

With the development of the times, modern society's risks have become increasingly evident. Faced with growing information uncertainty and the rapid development of the internet, people are more inclined to seek answers in the online space. According to the QuestMobile 2023 China Mobile Internet Annual Report and QuestMobile 2024 China Mobile Internet Spring Report, as shown in Figure 1, the number of mobile internet users in China surpassed 1.2 billion between 2020 and 2023 after four years of steady growth. The monthly active user base of China’s mobile internet grew from 1.145 billion in January 2020 to 1.227 billion in January 2024. Specifically, the net increase was 13.03 million from January to December 2020, 12.26 million from January to December 2021, 22.14 million from January to December 2022, and 24 million from January 2023 to January 2024. The overall trend shows a steady increase in user numbers, indicating the growing reliance on mobile internet among the population (Figure 1)

|

Figure 1. Monthly Active Users of China's Mobile Internet (2020-2023).

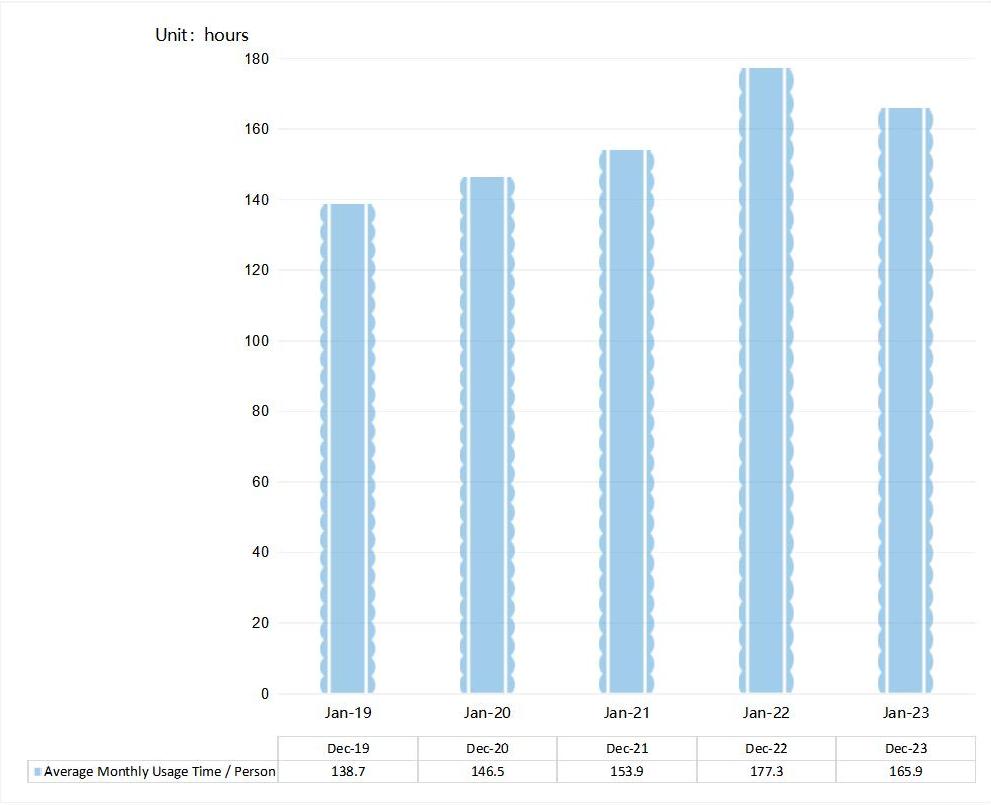

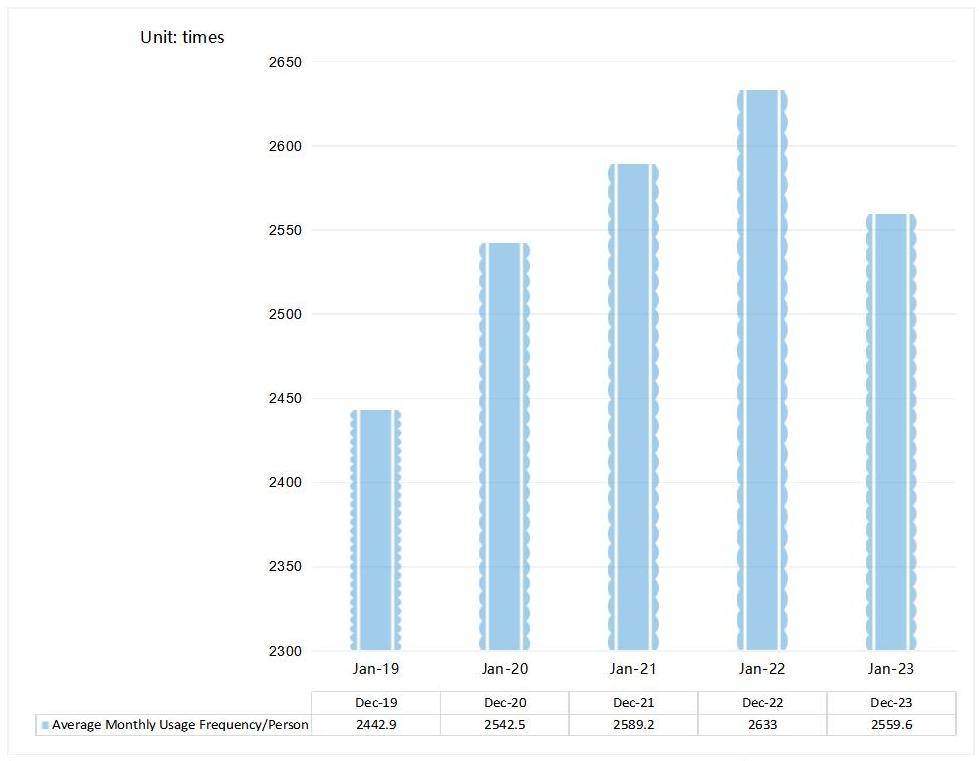

According to the QuestMobile 2023 China Mobile Internet Annual Report, as shown in Figures 2 and 3, the average monthly time spent online per user increased from 138.7 hours in December 2019 to 177.3 hours in December 2022, representing a growth of 27.83%. Additionally, the average monthly usage frequency per user increased from 2,442.9 times to 2,633.0 times, a growth of 7.78%(Figures 2 and 3). As people's dependence on mobile internet gradually increases, the time cost spent on app usage also rises. Besides enjoying the vast amount of free information provided by mobile clients, users are subtly influenced by a variety of information[2].

|

Figure 2. Mobile Internet Usage Behavior in China (2019-2023).

|

Figure 3.Mobile Internet Usage Behavior in China (2019-2023).

2.1.2 Younger Demographics in Internet Usage

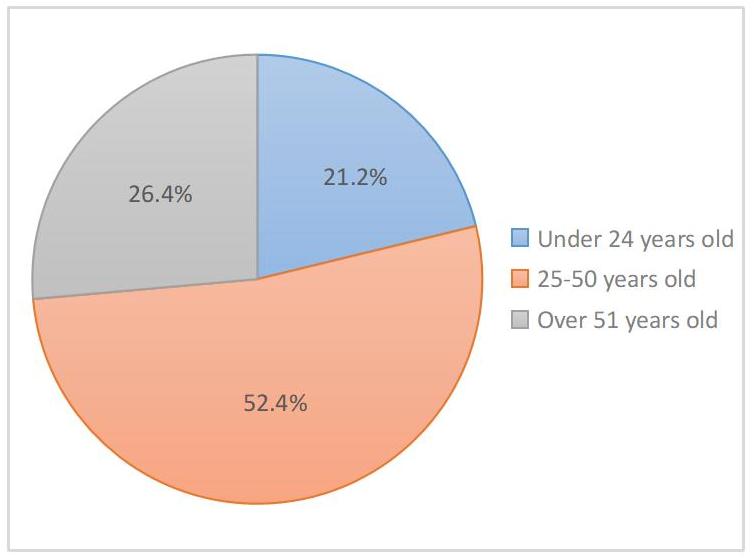

With the development of technology and the times, along with the widespread adoption of the internet, the total number of China's mobile internet users has been continuously increasing. According to the QuestMobile 2022 China Mobile Internet Annual Report, as shown in Figures 4-7, data from the end of 2019 and the end of 2022 indicate that young people remain the primary source of internet users. The age group of 25 to 50 years old has the highest proportion, accounting for 52.4% of the total users as of December 2022(Figure 4).

|

Figure 4. Age Distribution of China’s Mobile Internet Users.

According to the QuestMobile 2023 China Mobile Internet Annual Report, the increase in internet users in 2023 mainly came from the younger and elderly populations, with a noticeable concentration of users in first-tier, new first-tier, and second-tier cities[3]. QuestMobile data shows that, compared to January and December 2023, the proportion of users born after 2000 and after 1960 both increased by 0.1 percentage points, while the share of users from first-tier, new first-tier, and high-tier second-tier cities increased by a total of 10.5 percentage points.

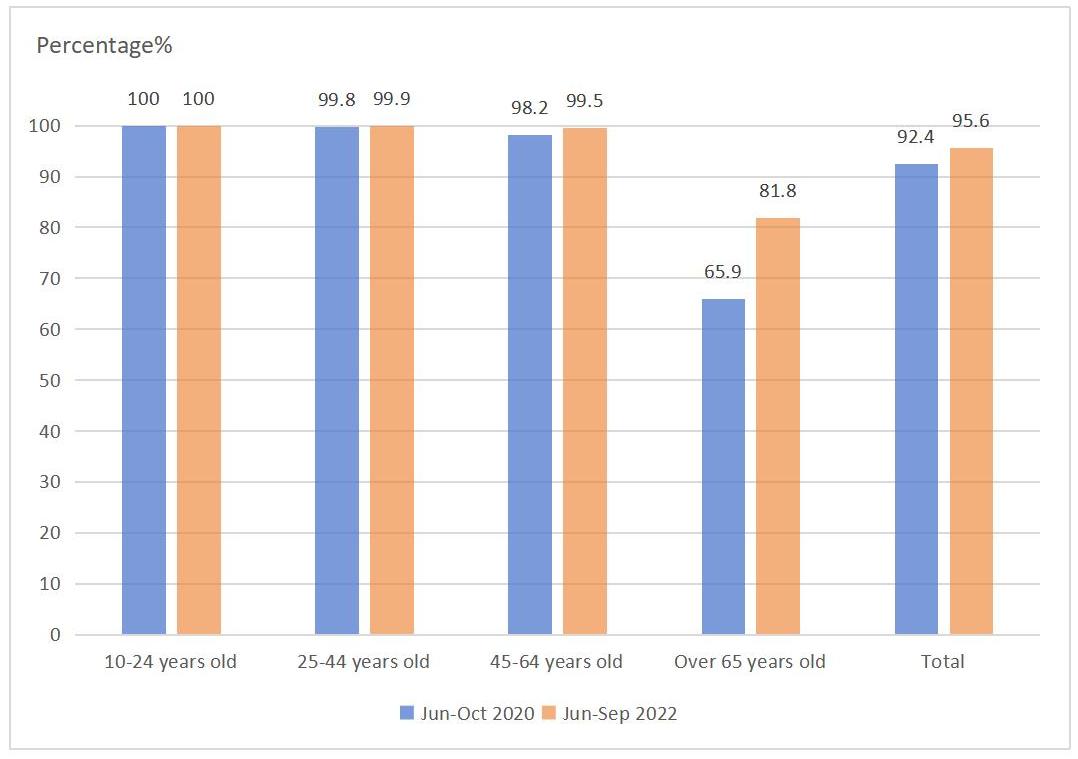

Additionally, according to Thematic Household Survey Report No. 77 published by the Census and Statistics Department of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government, almost all individuals aged 10-54 had used the internet within the 12 months prior to the survey, with usage rates ranging from 99.7% to 100.0%. As shown in Figure 5, among the surveyed population in 2022, the internet usage rate for those aged 25-44 was 99.9% over the past 12 months[4]. This indicates that nearly all young people in Hong Kong use the internet. The internet usage rate among the 10-24 age group was 100.0%, clearly demonstrating the trend towards younger internet users. Young people have become the main force on the internet, which has become the primary platform for them to access information, express political views, and organize actions through social media(Figure 5).

|

Figure 5. Percentage of Individuals Aged 10 and Above Who Used the Internet in the Past 12 Months, by Age Group (2020 and 2022).

According to Thematic Household Survey Report No. 77 published by the Census and Statistics Department of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government, as shown in Table 1, when analyzed by economic activity, 99.8% of individuals engaged in economic activities and 99.3% of students who used the internet in the past 12 months used it daily. In contrast, the corresponding percentages for homemakers and retirees were lower. This indicates that individuals engaged in economic activities and students use the internet most frequently, with young people having a high frequency of internet use (Table 1).

Table 1. Number of Individuals Aged 10 and Above Who Used the Internet in the Past 12 Months in 2022, Classified by Economic Activity.

Status |

Number of People (in ten thousand) |

Percentage(%) |

Ratio |

Engaged in Economic Activity |

356.4 |

58.1 |

99.8 |

Not Engaged in Economic Activity |

257.4 |

41.9 |

90.4 |

Students |

69.9 |

11.4 |

100.0 |

Homemakers |

65.8 |

10.7 |

97.3 |

Retirees |

117.7 |

19.2 |

82.7 |

Others |

3.92 |

0.6 |

81.4 |

Total |

613.8 |

100.0 |

95.6 |

According to Thematic Household Survey Report No. 77 published by the Census and Statistics Department of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government, as shown in Table 2, an analysis by age group reveals that individuals aged 15-24 spend the most time on the internet each week, with an average of 44.0 hours per week[5]. This is followed by those aged 25-34, with an average of 41.9 hours per week, and those aged 35-44, with an average of 38.3 hours per week. This indicates that younger individuals use the internet most frequently, clearly demonstrating the trend of younger internet users (Table 2).

Table 2. Number of Individuals Aged 10 and Above Who Used the Internet at Least Once Per Week in the Past 12 Months, Classified by Weekly Internet Usage Time and Age

Time Spent on the Internet Per Week (hours) |

Age Group (unit: thousands) |

|||||||

10-14 |

15-24 |

25-34 |

35-44 |

45-54 |

55-64 |

≥65 |

Total |

|

<5 |

6.9 (2.4%) |

6.0 (1.1%) |

14.3 (1.7%) |

20.1 (2.0%) |

26.9 (2.6%) |

73.9 (6.2%) |

242.0 (20.4%) |

390.1 (6.4%) |

5-<10 |

14.6 (5.0%) |

16.2 (2.9%) |

27.2 (3.2%) |

44.3 (4.5%) |

75.9 (7.3%) |

152.1 (12.8%) |

239.3 (20.2%) |

569.6 (9.3%) |

10-<20 |

42.8 (14.6%) |

36.1 (6.4%) |

61.1 (7.1%) |

105.5 (10.8%) |

158.8 (15.3%) |

215.9 (18.2%) |

243.0 (20.5%) |

863.2 (14.1%) |

20-<30 |

60.0 (20.5%) |

60.0 (10.6%) |

107.4 (12.5%) |

153.9 (15.7%) |

206.1 (19.9%) |

266.1 (22.4%) |

244.8 (20.7%) |

1098.4 (18.0%) |

30-<40 |

61.3 (20.9%) |

104.1 (18.4%) |

171.2 (19.9%) |

200.9 (20.5%) |

221.7 (21.4%) |

232.1 (19.6%) |

122.9 (10.4%) |

1114.2 (18.2%) |

40-<50 |

52.9 (18.1%) |

143.6 (25.4%) |

224.7 (26.1%) |

237.8 (24.2%) |

194.0 (18.7%) |

146.0 (12.3%) |

56.3 (4.8%) |

1055.2 (17.3%) |

50-<60 |

34.3 (11.7%) |

107.4 (19.0%) |

134.6 (15.6%) |

101.2 (10.3%) |

75.6 (7.3%) |

50.5 (4.3%) |

17.1 (1.4%) |

520.8 (8.5%) |

60-<70 |

7.0 (2.4%) |

26.1 (4.6%) |

29.8 (3.5%) |

30.0 (3.1%) |

18.4 (1.8%) |

12.5 (1.1%) |

4.0 (0.3%) |

127.7 (2.1%) |

≥70 |

13.1 (4.5%) |

66.8 (11.8%) |

91.5 (10.6%) |

87.3 (8.9%) |

60.7 (5.9%) |

37.0 (3.1%) |

15.0 (1.3%) |

371.4 (6.1%) |

Total |

293.0 (100.0%) |

566.3 (100.0%) |

862.0 (100.0%) |

981.0 (100.0%) |

1038.1 (100.0%) |

1186.1 (100.0%) |

1184.3 (100.0%) |

6110.7 (100.0%) |

Average time (hours) |

34.5 |

44.0 |

41.9 |

38.3 |

33.3 |

27.2 |

18.0 |

32.2 |

2.1.3 Usage Differences

With the continuous development of the internet, a variety of apps have become an indispensable part of people's daily lives[6]. However, for Hong Kong youth, the mainstream apps are still those developed by foreign companies, such as Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, Instagram, and Telegram (Table 3). In contrast, Mainland Chinese youth primarily use domestically developed apps like WeChat, QQ, and Weibo. This shows that there is little overlap in app usage between Hong Kong and Mainland youth, leading to significant differences in the apps they use (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of the use of mobile phone software by adolescents in the two places

Software Type |

Hong Kong Adolescents |

Mainland China Adolescents |

Social Networks |

QQ Zone |

|

Social/News |

||

Social/News |

WeChat Moments, Xiaohongshu |

|

Communication |

Whatsapp、Telegram |

WeChat、QQ |

News |

Apple Daily, Stand News, Oriental Daily, Sing Tao, Ming Pao, HK01, Headline Daily, AM730, Metro Daily |

Tencent News, Jinri Toutiao |

Forums |

LIHKG, HKGolden, HK Discuss |

Douban, Zhihu, Tieba |

TV Drama Streaming |

NOW, Netflix, myTV (TVB official app), HKTV (Hong Kong TV) |

Youku, Tencent, iQIYI |

Video Platforms |

Youtube |

Youku, Tencent, iQIYI |

Short Videos |

Tik·Tok |

Douyin, Kuaishou |

Stranger Social Networks |

Tinder、Coffee·meet·bagel |

Tantan, Momo, Soul |

Lifestyle Information |

Open·Rice、Tasty |

Dianping |

Food Delivery |

Food·Panda |

Meituan, Ele.me |

Local Events |

Timable |

Douban Local Events |

Map Apps |

Google·Map |

Baidu Maps, Amap |

Travel Apps |

Airbnb、Booking、Agoda |

Ctrip, Qunar |

Payment Apps |

PPS Payment, Apple Pay, Octopus App |

WeChat, Alipay |

Taxi Apps |

UBER、GOGOVAN |

Didi |

Weather Apps |

Hong Kong Observatory |

Moji Weather |

Music & Social Apps |

Spotify、JOOX、MOOV |

QQ Music, NetEase Cloud Music, Kuwo, Xiami, Kugou |

Shopping Information |

Hong Kong Price Watch, Pinterest |

Smzdm (What’s Worth Buying), Xiaohongshu |

2.1.4 Content: Hong Kong Apps Offer a Broader Range

The apps used in Mainland China primarily target domestic users, while Hong Kong users tend to use more foreign apps[7,8]. These foreign apps have a larger user base and cater to a broader audience, with more diverse social groups. As a result, the content offered by these apps tends to be more extensive.

2.1.5 Functionality: Mainland Apps Are More Refined

Mainland apps are developed primarily for a domestic audience, and the companies behind them have a more precise understanding of user habits and preferences. This allows for more detailed and refined functionality within the apps. In contrast, the apps commonly used in Hong Kong serve a larger, more diverse user base, leading to a less clear understanding of user habits and lower levels of functionality refinement. Therefore, Mainland apps tend to offer more advanced and comprehensive features[9,10].

3 RESULTS

The quantitative results revealed significant differences in mobile application preferences between adolescents in Hong Kong and Mainland China. Adolescents in Hong Kong showed a preference for global platforms such as Instagram and Facebook, while their counterparts in Mainland China predominantly used local platforms like WeChat and Weibo[11]. The data indicated that these differences were influenced by various sociological factors, including class, education, and access to technology[12-14]. Qualitative findings highlighted that adolescents in Hong Kong were more inclined towards using social media for political discourse, whereas Mainland Chinese adolescents used platforms primarily for entertainment and social interaction. Content analysis further revealed that platform-specific algorithms contributed to the creation of distinct informational silos, reinforcing the development of parallel virtual societies[15].

4 DISCUSSION

The findings of this study reveal that the differences in mobile application usage between adolescents in Hong Kong and Mainland China can be explained through multiple factors, including product positioning, cultural differences, and market dynamics.

4.1 Product Positioning

Product positioning plays a significant role in shaping app usage patterns between the two regions. Hong Kong, being a highly internationalized metropolis, has attracted global tech companies like Facebook and Instagram early on. These platforms established their market presence well before Chinese domestic apps, which primarily focused on Mainland users. The product positioning of foreign apps, which targeted an international audience, contrasts sharply with Mainland Chinese apps that were designed for local needs and preferences. This divergence has led to a digital environment where adolescents in Hong Kong and Mainland China predominantly use different sets of apps, contributing to the formation of distinct virtual communities.

4.2 Cultural Differences

Cultural differences further exacerbate the divergence in app usage. The language preferences in Hong Kong and Mainland China are key factors driving these differences. Hong Kong residents primarily use Cantonese and traditional Chinese characters, while Mainland Chinese users favor Mandarin and simplified characters. This linguistic distinction is a significant marker of identity, influencing the adoption of apps that cater to specific language preferences. Consequently, Hong Kong adolescents tend to use foreign apps that support traditional Chinese or English, while Mainland Chinese adolescents gravitate towards local apps that align with their linguistic and cultural context. These cultural differences not only determine the choice of apps but also shape the content consumed, leading to divergent digital experiences and reinforcing the concept of virtual parallel societies.

4.3 Market Factors

Market dynamics also play a crucial role in shaping app usage. The aggressive market capture by foreign companies in Hong Kong, coupled with the reluctance of Mainland Chinese companies to adapt their products for the Hong Kong market, has resulted in limited market penetration for Chinese apps in Hong Kong. Many Mainland-developed apps are either unavailable or lack localized features that cater to the cultural and linguistic preferences of Hong Kong users[16]. This has created an environment where Hong Kong adolescents are more inclined to use well-established foreign apps, while Mainland adolescents rely on domestic platforms. The lack of overlap in app usage between the two regions contributes to the creation of informational silos and the development of parallel digital societies.

4.4 Formation of a Virtual Parallel Society

The concept of a "parallel society" can be extended to the digital realm, where distinct app usage patterns among Hong Kong and Mainland Chinese adolescents create separate informational ecosystems. These virtual parallel societies are characterized by different sources of information, modes of communication, and cultural narratives. Adolescents in Hong Kong and Mainland China are exposed to vastly different content due to the platforms they use, leading to divergences in political and cultural understanding. This phenomenon is similar to the "pseudo-environment" described by Walter Lippmann, where the information environment constructed by mass media shapes people's perceptions of reality. The creation of such distinct digital environments contributes to a lack of mutual understanding and may hinder harmonious interaction between the two regions.

4.5 Distortion of Political Perception Among Youth

The differences in app usage also contribute to the distortion of political perceptions among adolescents, particularly in Hong Kong. The open discourse framework of foreign social media platforms allows for a wide range of political views, including those that may be critical of Mainland China. This has led to the proliferation of content that can influence the political attitudes of Hong Kong youth, especially during times of political unrest. In contrast, the more controlled environment of Mainland Chinese platforms limits exposure to dissenting views, resulting in a different political narrative. The disparity in the type of information consumed by adolescents in the two regions further reinforces the divide in political perceptions and contributes to the challenges of building a cohesive national identity[17].

4.6 Policy Suggestions

4.6.1 Government and Civil Society: Going Global and Amplifying the Chinese Voice

In the media age, a barrage of diverse information and images bombards people's vision. People rely on different forms of media to follow society and participate in social activities, while synchronous media information constrains their imaginative horizons. Tempted by the constant flow and replacement of visual content, "cartoonish" image information has increasingly replaced in-depth written thinking. However, even traditional media like newspapers and magazines are showing a trend towards "no need to think, cartoonish" content.

Hong Kong youth, who use Western social media, naturally gravitate towards the Western discourse system, and they are distributed across key social systems such as civil service, education, law, and finance. Faced with the global competition of internet companies, building alternative solutions requires a multi-dimensional and gradual approach, and it will inevitably face multiple challenges.

National identity, at its core, can only be continuously constructed through communication, consultation, and dialogue. Hong Kong operates under the "One Country, Two Systems" framework, with capitalism's culture and values aligning with its economic and political systems. Facilitating cross-system dialogue, communication, and integration is of paramount importance. Compared to the judicial and education systems, the promotion of mobile software and social media faces fewer obstacles, making it a fundamental prerequisite for establishing "cultural confidence."

We should integrate the "Hong Kong spirit" into the narrative of the "Chinese Dream" to guide Hong Kong youth to gradually recognize that Hong Kong's destiny is closely linked with Mainland China. On one hand, the government can establish a position in public opinion, promote the Chinese voice, and facilitate social media platforms that enhance national identity by expressing viewpoints in "external" Western-dominated social media, thereby advancing Chinese social media globally. On the other hand, Chinese internet companies should be encouraged to place greater emphasis on Hong Kong and overseas markets, enabling Chinese social media platforms to go global and serve the world, breaking the traffic monopoly of Western, especially American, internet companies. Additionally, it is crucial to provide incubation or venture capital support to entrepreneurs working in Hong Kong who have Mainland backgrounds, so they can leverage their bridging role effectively.

4.7 Enterprises: Diversified Development and Expansion into the Hong Kong Market

As one of the regions in Asia that entered the internet era relatively early, Hong Kong proposed the goal of building an "international digital port" and explored internet-related technologies earlier on. However, foreign social media platforms developed before those in Mainland China, and they promoted their platforms in Hong Kong earlier, securing the Hong Kong market first. Although local internet platforms in Hong Kong began developing early, their progress in building a robust social network platform has been relatively slow, and there is a lack of large-scale social media platforms. The internet financial platform sector is also relatively underdeveloped, necessitating collaboration with Mainland companies for further development.

Under the "One Country, Two Systems" framework, the central government cannot directly push for educational and media reforms in Hong Kong. We need to consider how to reclaim the discourse power from foreign social media platforms, encouraging patriotic groups and Chinese internet companies to establish operations in Hong Kong, attract users, and ultimately achieve interconnectivity and cultural confidence in the Greater Bay Area, enhancing the identity of Hong Kong youth with "One Country."

Therefore, Chinese internet companies should be encouraged to pursue diversified development and place greater emphasis on the Hong Kong and overseas markets. For instance, in addition to launching international versions of apps like TikTok by ByteDance, other well-known Chinese social software such as Momo, Tantan, Soul, Kuaishou, Xiaohongshu, Douban, Zhihu, and WeSing can also increase efforts to attract new users and promote in the Hong Kong market.

Enhancements could be made in traditional Chinese versions, such as using GPS assistance to automatically convert simplified Chinese text from other Mainland users into traditional Chinese characters when users log in from Hong Kong, reducing the sense of separation and increasing the willingness of young people to try these apps.

4.8 Combining Online and Offline Efforts

The main ways Hong Kong and Macau youth learn about their country are through television, the internet, and print media. According to research, the three main media through which Hong Kong and Macau youth obtain national news are television, newspapers, and the internet, with direct exchange activities like visits and exchanges not being the primary way they learn about their country. Since the handover, the central government has upheld the principle of "high degree of autonomy and Hong Kong people administering Hong Kong" and has not interfered with Hong Kong's commercial and speech freedoms. However, after multiple incidents related to identity, relevant authorities need to recognize the value of existing social media in Hong Kong in disseminating values and actively mitigate the "virtual parallel society" experienced by youth in the two regions through a combination of online and offline efforts.

On one hand, short-term online and offline exchange programs can be studied. While short-term study tours and exchange activities can spark interest, to truly deepen the understanding of Mainland development and foster a sense of belonging to Mainland China among Hong Kong youth, it is essential to attract them for long-term, frequent exchanges, or to study, work, and live in Mainland China. Leveraging the geographical advantage of the Greater Bay Area high-speed rail network, diverse offline activities and meetups can be organized, focusing on animation, gaming, internet influencers, and social interactions to attract Hong Kong youth to spend weekends frequently in Guangzhou and Shenzhen. By aligning with their interests and leveraging Mainland venues, these activities can encourage Hong Kong youth to participate in offline events, promoting real-world social interactions between youth from both regions. This can also lead to increased usage of Mainland social software, such as WeChat and WeChat groups.

On the other hand, leveraging the vast and diverse resources of Mainland China, as well as the more affordable options for dining, entertainment, and leisure, can encourage Hong Kong youth to step outside the confines of online content algorithms and gain a multifaceted understanding of the development in the Greater Bay Area. While school education is an important setting for young people to form their values, it is not the only one. In the short term, enhancing offline social interactions and leisure activities between young people from both regions—what could be termed "light exchanges"—can help counteract the misleading influence of Western social media on young people, alleviate the anxiety and hostility that some Hong Kong youth feel towards the Mainland, and foster friendships with Mainland peers. This, in turn, can encourage Hong Kong youth to use Chinese social media platforms and maintain connections within their "circle of friends," helping to cultivate a generation of young people who understand China, are not opposed to China, and are even pro-China and patriotic towards Hong Kong.

5 CONCLUSIONS

A significant number of those arrested during the "Anti-Extradition Bill Movement" were young students, and youth represent the future of Hong Kong. Addressing how to reduce the influence of foreign forces and the Hong Kong opposition in misleading young people's thoughts through social media, and enhancing national identity among Hong Kong students, is an urgent issue. This study, which focuses on various social media apps, finds that young people frequently use the internet, with a noticeable trend toward younger internet users. Due to differences in product positioning, cultural factors, and market considerations, there are discrepancies in social media usage between Hong Kong and Mainland youth. These differences have led to deviations in national and cultural identity among young people from the two regions, gradually giving rise to a "parallel society" phenomenon. This, to some extent, has resulted in the realization of a pseudo-environment, hindering better communication and development between the two regions.

To address this issue, the following solutions are proposed:

Firstly, both the government and civil society should take proactive steps to amplify China's voice globally. The government can establish platforms on social media to promote Chinese perspectives and enhance national identity, while encouraging Chinese internet companies to place greater emphasis on the Hong Kong and overseas markets.

Secondly, businesses should focus on diversified development and enter the Hong Kong market.

Finally, relevant authorities need to recognize the role of existing social media in Hong Kong in spreading values, and actively use a combination of online and offline methods to alleviate the "virtual parallel society" experienced by young people in both regions, thereby promoting real-world social interactions between them.

Policy recommendations for enhancing national identity among Hong Kong youth should consider the feasibility of interventions in the current socio-political context. Media literacy programs that foster critical engagement with digital content could serve as a potential solution to bridge the divide and mitigate the effects of virtual parallel societies.

Acknowledgements

This paper is a phased research outcome of the 2020 Guangdong Province Regular Higher Education Youth Innovation Talent Project (Humanities and Social Sciences) "Virtual and Real Society" – A Comparative Study on the Use of Social Media by Youth in Hong Kong and the Mainland (Project Number: 2020WQNCX080).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declared no conflict of interest.

Author Contribution

TSEUNG Yik Wong was the primary researcher and wrote the manuscript. Binyu Xie provided research and editing assistance to the manuscript. Ziting Peng contributed to overall article design, data collection as well as revising and approving the manuscript.

References

[1] Wang F."The value implication of"patriots administering Hong Kong and its educational realization: Based on the perspective of national identity of young students in Hong Kong, China [In Chinese]. J Shanghai I Socialism, 2023; 94-102.[DOI]

[2] Yang X. Research on mobile public opinion and national image identity [In Chinese]. Shanghai Normal University; 2023.

[3] Zhang Y. Research on the urgency of the construction of national identity of Hong Kong youth [In Chinese]. J Guangzhou I Socialism, 2020; 6.

[4] Lin W. Urgent Issues and Countermeasures for the Development of Hong Kong Youth [In Chinese]. J Guangdong I Socialism, 2017; 40-44.

[5] Wang Y, Apian Chen. Cross-lag Analysis of Adolescent National Identity and Self-esteem [In Chinese]. 2022.

[6] Han L. The main basis, development trend and educational approach of adolescents' national identity [In Chinese]. Chinese Youth Stud, 2021; 6.

[7] Zhang H. Reflection on the national identity crisis of Hong Kong adolescents and improvement countermeasures [In Chinese]. Chinese Moral Educ, 2017; 29-33.

[8] Gao Y. Research on the influence of online public opinion on adolescents' national identity and countermeasures [In Chinese]. People of the Times, 2023; 0129-0131.

[9] Chen Z. The basic status quo and policy suggestions of national identity of Hong Kong and Macao teenagers studying in Guangdong [In Chinese]. J Guangzhou I Socialism, 2024; 70-78.

[10] Xu S. Thinking on the current situation and path of national identity education for teenagers [In Chinese]. Class Teacher, 2024.

[11] Dai X, Zhen M. The implementation path and future prospect of national identity education for Hong Kong youth [In Chinese]. Chinese Moral Educ, 2023; 40-44.

[12] Du T, Wu G. History Education and National Identity: Rethinking the Construction of National Identity for Hong Kong Youth. SAR Pract Th, 2018; 4.

[13] Du T, Wu G. The construction logic of adolescent national identity [In Chinese]. Journal of Guizhou Provincial Party School, 2018; 6.[DOI]

[14] Chen L. Reasons and ways out of the lack of national education for young people in Hong Kong [In Chinese]. Curriculum. Teaching materials. Shariah, 2019; 7.

[15] Li L. Patriotic Education for Hong Kong Youth in the New Era: Generative Logic and Practical Path [In Chinese]. 2024; 117-119.

[16] Zheng Z." Research on the rule of law path of Hong Kong youth national identity construction under "one country, two systems" [In Chinese]. Chongqing Technology and Business University; 2022.

[17] Zhang L. Self-Presence in the Public Sphere: A Study on Media Literacy Traits of Hong Kong Youth Modern Communication [In Chinese]. Journal of Communication University of China, 2019.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). This open-access article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Copyright ©

Copyright ©