The Agential Causes of Business Management Students in the Implementation of the Full Virtual Teaching

Li Li1*, Lu Liu1, Anna Walker2, Jing Wang3, Inna Pomorina1, Victoria Opara1

1Bath Business School, Bath Spa University, Bath, UK

2External Affairs Unit, Bath Spa University, Bath, UK

3Ning Xia University, Yinchuan, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, China

*Correspondence to: Li Li, PhD, Bath Business School, Bath Spa University, Newton Park, Newton St Loe, Bath, BA2 9BN, UK; Email: l.li2@bathspa.ac.uk

Abstract

Objective: This study investigates the agential causes influencing undergraduate business management students in their handling of change. The objectives are: (1) To investigate emotional reactions experienced by students since the launch of full virtual teaching as a result of the COVID-19 outbreak. (2) To investigate the students’ concerns in their lived experiences. (3) To identify commonalities and differences in students’ experiences during the implementation of full virtual teaching induced by COVID-19 in the socio-cultural contexts of China, the UK, and Ukraine.

Methods: This research employed an embedded multiple-case design, following the logic of literal and theoretical replication. One-to-one interviews were conducted, involving a total of 61 business management students. All scripts were analyzed using framework analysis and summative content analysis.

Results: The study found that all sampled students have experienced a wide range of emotions as emerged from their reflexive accounts of their lived experiences associated with full virtual teaching as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. A discernible trajectory of emotional changes was observed. The students’ primary concerns evolved as situations progressed, with the desire to return to campus being pronounced at the beginning of the change and intensifying over time. Additionally, the study identified differences in emotional reactions and considerations of personal development between Chinese students and their counterparts from other socio-cultural backgrounds.

Conclusion: Emotions, reflexivity, absence, and absenting are influential factors shaping student experiences.

Keywords: emotions, reflexivity, social equity, socio-cultural, students

1 INTRODUCTION

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on societies differs significantly from the relatively optimistic sentiment reflected in the 1975 record ‘Crisis? What Crisis?’[1]. This period has brought forth challenges[2,3] as well as opportunities[4] for higher educational institutions (HEIs), teaching staff[5,6], parents[7], and individual students[8,9], especially those in vulnerable positions[10]. Beyond the less optimistic aspects, there is another side characterized by resilience and creativity demonstrated by HEI leaders[11], faculties[12], and students, leading to the transformation of learning and teaching practices.

While the closure of campuses and the subsequent shift to fully virtual teaching limited physical movement, it also fostered new social dynamics. This includes the emergence of existential (a more authentic self) and spatial (i.e., security) privileges[6], as well as initiatives to re-shape the education system[2]. Realistically speaking, transformative practices or morphogenesis[13,14] have emerged and are being elaborated in many countries.

However, such a sudden closure and implementation of full virtual teaching assumed that (1) all university students would have access to the necessary technology to continue their studies during the pandemic and (2) they would attend all online sessions, whether willingly or not. These assumptions inherently address issues of social equity. But, can all students access the required technology? To what extent can they commit to online sessions when their life arrangements are disrupted by the uncertainty of the future?

Indeed, how did students genuinely perceive their learning experience during the pandemic? What were their thoughts on pursuing higher education in a restricted context? These questions hold significance not only for their well-being but also for their learning outcomes. This paper adopts a critical realist approach to address these questions. Specifically, this study investigates how students’ reflexivity and emotions were triggered and manifested during the pandemic. Additionally, it aims to uncover any variations based on the socio-cultural contexts in which students were operating.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Reflexivity

Reflexivity is intrinsic to all human activity[15], a characteristic of human action[16]. Maclean et al.[17] regard reflexivity as a human capability that involves constructing an understanding of ‘the location of self within a social system’, reflecting on and redefining their understanding of the surroundings. It is seen as depending on conscious deliberations conducted through internal conversation, often taking the form of question and answer[18]. It is through this powerful human agency, we reflect upon the world and question ourselves about our ultimate concerns and what we should do[19], which entails a strong evaluation of our social context in light of our concerns[20].

2.1.1 ‘I’ and ‘My Surroundings’

In alignment with Archer’s perspective[13,14,19,21], individuals possess the power to make sense of reality through the human agency of ‘thinking’ and to change the environment through ‘doing’. The interpretation of individuals in their relations with the external environment is conditioned by the latter. This environment results from structural, cultural, and agential elaborations in the antecedent morphogenesis cycle, preceding the actions of present agents. Despite the constraints and enabling factors imposed by the distribution of resources and rules in the environment, individuals have the power to make a difference. Human experience emerges from these relations with the environment and the capacity to comprehend the world, dealing with change through creativity.

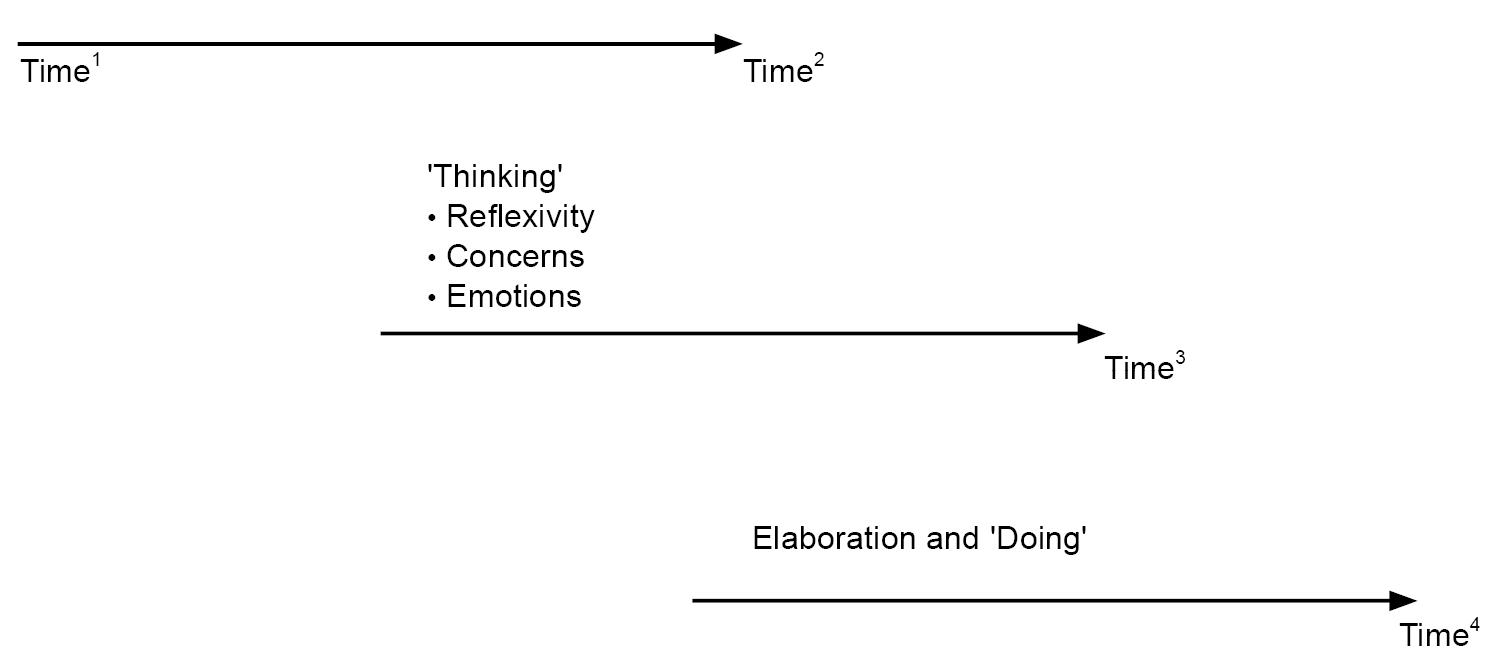

This argument for the emergence of human experience is underscored by recent events related to the COVID-19 pandemic (see Figure 1). The global pandemic has resulted in rapid and unexpected changes in societal interactions, with social distancing becoming a norm in many countries to ensure safety. In response to this abrupt change, universities had to transition their teaching to virtual spaces. This situation presented a unique challenge for students.

|

Figure 1. The emergence of student experience. Adapted from Archer[13]. Reproduced with permission of The Licensor through PLSclear.

However, we shall argue, that instead of being simply passive subjects of the change, the students possess properties and powers that enable them to arrive at a course of actions, or ‘strategies’, to handle the changes. A student’s experience emerges from the person’s interactions with the changing environment, encompassing the natural, practical, and discursive orders of reality[21]. This experience entails the individual’s knowledge that relates to the three realms: physical, emotional / conceptual, and theoretical[22]. These interactions are engineered through the human agency of ‘thinking’ and ‘doing’.

2.1.2 ‘I’ and ‘My Thoughts’ (Reflexivity, Ultimate Concern, and Emotion)

Our reflexivity enables us to make personally meaningful choices and to develop a course of action aimed at sustaining or enhancing our concerns. Central to these concerns are our well-being, performative achievement, and self-worth, all of which emerge from our relationships with the natural, practical, and discursive orders of reality-encompassing body-environment, subject-object, and subject-subject interactions[21]. According to Archer[21], these concerns are socially molded through our reflections upon what holds significance in our inescapable social lives. Our ability to monitor and anticipate emotions associated with objects and our relations with them, along with social normativity, further shapes these concerns.

In essence, our concerns depict ‘what we value’[21]. For value to be meaningful, it must have a ‘host’ the value of something. Whether an object, social status, or a relation with an object or subject, something is considered “valuable” due to its significance to our concerns arising from our interactions with the three orders of reality: body-environment, subject-object, or subject-subject relations, respectively. Our concerns are ineluctably accompanied by our commentaries, i.e., emotions. In our inner conversations, we provide commentaries on what we value—expressing our feelings about our concerns.

2.1.3 ‘I’ and ‘My Actions’ (Habits, Opportunities, and Emotions)

The bio-social changes induced by the COVID-19 pandemic have disrupted our habitual rules and patterns of social interaction. Change, as Archer notes, involves a mode of absence / absenting[23]. It gives rize to reflexive imperatives replacing ‘habits’ and relational reflexivity realising socialisation[19]. Reflexive ‘thought and talk’, according to Archer, results in internal elaboration of various projects-possible ways to satisfy and sustain ultimate concerns. Bhaskar[24] highlights the characteristic structure of intentional action: present absence → orientation of the future → grounding in the presence of the past → praxis. Our ultimate concerns, representing a prioritized list of our worries, are evaluated through reflexivity, where we elevate some emotions and subordinate others, aligning them with concerns we feel we can live with. Imaginative projects are chosen based on external resources and evaluative assessments of our capabilities, and action plans are developed, some of which are implemented to address the absence.

This perspective aligns with Schneider and Goldwasser’s[25] change curve, illustrating that change may entail loss and pain for those affected by it. In the context of virtual education due to COVID-19, students’ social interactions with peers and tutors have transitioned solely to the virtual realm, eliminating in-person social engagement. This absence may generate heightened expectations and concerns[8-10]. Subsequently, the recognition of effort and the complexity associated with virtual learning from home may lead to a dip in morale. However, with continuous efforts and the passage of time, positive outcomes may emerge[8,26], symbolizing a light at the end of the tunnel[24]. This is so because the new practice has made the acquisition of what was absent possible. As articulated by Archer[13], the ongoing process of being shaped by and shaping the environment allows individuals to transform themselves in terms of their ultimate concerns and interests.

2.2 Emotions

The previous two subsections conjoin an important human experience - emotions. While ‘emotion’ is a well-established psychological category, consensus on its definition remains elusive within the psychological community. Izard[27] provides a description that encompasses ‘neural circuits’ (at least partially dedicated), response systems, and a feeling state / process that motivates and organizes cognition and action. Some scholars[20,28] differentiate emotion from passion and affection, highlighting its secular, morally neutral evolution and its scientific character, departing from theological and spiritual perspectives of the human person.

Despite the lack of universal agreement, there is a consensus that emotions differ from forms of thought. Emotions, according to this view, ‘vivid feelings’ derived immediately from the consideration of objects (perceived, remembered, or imagined) or from ‘other prior emotions’[29]. They are affective modes of awareness in response to a situation or as bodily commentaries on our concerns[20,21,30-32], arising from how well or badly we handle objects in our effort to address our concerns and from our relationships with others and societal normativity[21].

Emotions are inherently relational-they are not generated out of nowhere. When the object of an emotion falls within the natural order, where our ultimate concerns revolve around well-being, bodily pleasure, and pain become the foundations from which emotions such as fear, hope, and relief[21]. Emotions differ depending on performance: students may feel frustration if they cannot hear a live virtual lecture clearly because of an unstable Internet connection (a first-order emotion) and thus may feel anxious about their performance in their assessment (a second-order emotion). Conversely, they may feel content about the 24/7 availability of online learning materials, perceiving greater control over their progress. Thus, the two orders of emotions can emerge almost spontaneously.

Emotions significantly influence our decision-making and actions[27,29,33-35]. Choosing to be a university student exposes individuals to emotional experiences related to family, peers, tutors, and normative evaluations of their academic performance. The emotions students undergo serve as indicators of their progress in studies, involving a sense of hope for approval or fear of disapproval regarding their performance. Hence, emotions are not only mental states with outward bodily expressions; they are also attached to aspects that matter to us. As such, emotions act as influential factors shaping our thinking, decision-making processes, actions, social relationships, well-being, and physical and mental health[27].

The role of students’ emotions in online learning has been examined in various empirical studies. Emotions are explored in relation to learning effects[36], learning engagement[37,38], satisfaction[39], and knowledge construction[40]. The conceptual frameworks of these studies vary; for instance, Wu et al.[39] position enjoyment and boredom as mediating variables that condition the relationship between learner-context interaction and satisfaction. Similarly, Wang et al.[38] describe the mediating effect of emotions on the relationship between interaction and future online learning tendencies. Lv and Yang[36] and Wen[40] have reported a positive correlation between emotion and learning outcomes.

In contrast, Berweger et al.[41] and Cheng et al.[42] seek to examine how positive emotion is related to learning situations by using expectancy-value appraisals. Following Pekrun[43], these two studies reduce emotions to achievement emotions such as frustration, enjoyment, and boredom experienced in learning, and outcome emotions, for instance, joy, hope, shame, or anger related to success or failure. In line with the tenets of Pekrun’s control-value theory of achievement emotions, these two studies confirm aspects proposed in the theory, adding limited insights into the understanding of emotions in students’ learning. However, Shao et al.[44] regard perceived control and value as mediating variables while introducing perceived teacher competence in information and communication technology and teaching structure as independent variables. They show how emotions (including anxiety, boredom, and enjoyment) are influenced by the independent variables and how they are mediated by the mediating variable.

These empirical studies have predominantly embraced a positivist approach, aiming to identify correlations either suggested by existing knowledge or claiming the existence of relationships between variables through statistical analyses such as structural equation modelling[39]. Realists argue that a correlation provides a pattern of one event after another; however, it does not explain how one causes another[45]. The outbreak of COVID-19 was followed by a move to sole online learning in almost all the countries that were affected by the pandemic; however, the real causes of the ensuing virtual learning and teaching are considerably more complicated than the outbreak itself. The mere occurrence of events does not inherently explain the causal relationships between them. Causation is a central focus of realist research. This paper specifically delves into causation, exploring the processes through which reflexivity and emotions-both agential properties inherent in humans-operate to bring about learning experiences of university students within the context of COVID-19.

Informed by the literature reviewed above, the following research objectives are set: (1) To investigate the emotional reactions that students have experienced since the launch of full virtual teaching following the outbreak of COVID-19. (2) To investigate the students’ concerns in their lived experiences. (3) To identify the commonalities and differences in the experiences of students during the implementation of full virtual teaching induced by COVID-19 across the socio-cultural contexts of China, the UK, and Ukraine.

3 METHODOLOGY

3.1 Research Strategy

This research employed an embedded multiple-case design[46-50] to facilitate cross-cultural analysis. Five HEIs were selected, including two business schools (BSs) in China, two in Ukraine, and one in the UK (hereafter referred to as BS_A, BS_B, BS_C, BS_D, and BS_E in that order). BS_A and BS_B are higher education institutions, located in Yinchuan (the capital of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region in northwest China) and Wuhan (the capital of Hubei Province in central China), respectively. At the time of the study, BS_A had over 400 students, with approximately 75% being female, while BS_B had over 1000 students, of which 60% were female. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, teaching shifted online in February 2020 in China, resuming offline teaching in August / September 2020 for BS_A and June 2020 for BS_B.

The lockdown in Ukraine started in March 2020, when BS_C and BS_D had to transition all teaching online. BS_C utilized Moodle, and BS_D delivered online courses through its own virtual learning environment. To prepare academic staff for online teaching, training programms were introduced. Students attended virtual classes from their homes, student accommodations or rented apartments, facing challenges like varying Internet speeds. BS_C hosted over 2,700 economics students, with 58% being female, while BS_D had 1780 students enrolled in Business Management and Economics programmes, with 65% being female.

BS_E, based in UK, used a virtual learning environment in teaching before the pandemic started. Teaching was transitioned to online only from March to May 2020, followed by blended learning. All academic staff have received training on the use of a range of programmes, such as Google Meet and Jumpboard, to complement the functions of the virtual learning environment. The school had approximately 900 students, around 70% of whom were female at the time of the study.

Within each business school, individuals who met the criteria of experiencing university studies before the shift to solely virtual learning were invited to participate in the study. The response to the initial call fell below expectations. The second call for participation was then initiated by the researchers in their respective institutions. This time, a more personalized invitation was sent to several students who had been actively engaging in their classes, with an aim to recruit at least ten participants in each school. Gender distribution within the programme and the level of study were taken into consideration to ensure a diverse representation of both male and female students across different levels of study in the sample. The personalized approach yielded targeted outcomes, providing a sufficient number of participants for data saturation[46-49].

The design of the study adhered to the logic of literal replication - the participants within their respective socio-cultural context may share some similarities in their virtual learning experiences. It also followed a theoretical replication based on the assumption that the three socio-cultural contexts provide different conditions for these individuals’ experiences. This variation could arise from factors such as varying degree of virtual learning environment adoption in universities and of COVID-19 restrictions in these contexts. Thus, such a design facilitated a comparative analysis of the cases across the contexts.

3.2 Data Collection

Data were collected almost contemporaneously by the research team between November 2020 and January 2021. A temporally sequential data collection procedure was considered inappropriate due to the sensitivity of self-reported virtual learning experiences to time and real-life socio-cultural contexts. One-to-one semi-structured interviews were conducted in-person, remotely via telephone, or virtually, considering practicality in terms of availability and COVID-19 restrictions. Faculty members from the respective BSs conducted the interviews, which were recorded and / or documented. To overcome ethical concerns regarding power dynamics, participants were informed beforehand that participation was voluntary and would not impact their grades.

In one Chinese business school, in-person interviews were conducted as all participants were on campus at the time, while interviews in the other Chinese business school were carried out remotely via telephone because participants had returned home after the term. All interviews in China were conducted in Chinese. In Ukraine, interviews were conducted online in Ukrainian and / or Russian and translated into English for analysis. In the UK, interviews were conducted in English using Google Meet and Google Docs[51] due to COVID-19 restrictions at the time of data collection.

In total, 61 business management students participated in this study. As outlined in Table 1, 50% of Chinese students were in their second year; the Ukraine sample was dominated by first- and second-year students, while the UK sample consisted of second- and third-year students. Approximately 67% of the participants were females, roughly reflecting the overall gender distribution of students in these schools.

Table 1. The Portfolio of the Samples

Country |

No. of Participants |

No. of Females |

No. of Males |

Year 1 (Y1) |

Year 2 (Y2) |

Year 3 (Y3) |

Year 4 (Y4) |

China |

24 |

18 |

6 |

|

12 |

9 |

3 |

Ukraine |

21 |

12 |

9 |

10 |

10 |

1 |

|

UK |

16 |

11 |

5 |

|

6 |

10 |

|

3.3 Data Analysis

All interview scripts were imported into NVivo and analysed using framework analysis[52] and summative content analysis[53]. The analysis process adapted Nicolini’s[54] suggestion of zooming in and out in studying practice to facilitate abduction[55,56]. It involved mapping ‘local expressions’[54] of every participant’s account with theory-informed sub-themes. By setting the unit of analysis at the individual level, each account was redescribed in known theoretical insights. This was followed by a zooming-out exercise, shifting the unit of analysis to collectives defined by temporal terms, socio-cultural contexts, and participants’ year of study.

3.4 Research Evaluation

To ensure validity, dependability, and confirmability[57], the following actions were taken: Firstly, a pilot study was performed prior to the main field study to ensure that interview questions were understood, and answers were relevant to the research interest. Secondly, investigator triangulation[58] was employed, where the developed framework was applied to all cases by two team members, and coding was then reviewed by another two team members, identifying no significant discrepancies. Thirdly, the procedure of framework analysis[52] and a systematic case study protocol[50] were rigorously followed to minimize bias that can jeopardize the dependability. Fourthly, word frequency and matrix coding were conducted in NVivo, and queries were stored in the software to not only provide confirmability or traceability but also to avoid possible potential errors. Additionally, during data analysis and interpretation, the first author engaged reflexively with her situated voices, negotiating between the researcher and the researched to avoid tendential reductions of knowledge[59] and to be mindful of epistemic fallacy[60]-not conflating the actual with the real and avoiding epistemological predeterminism with ontological determination[23].

4 FINDINGS

The participants were asked ‘how did you feel on the first day of virtual university?’ (i.e. Moment 1) and ‘how are you feeling now?’ (i.e., Moment 3). Moment 1 refers to March 2020 for participants in Ukraine and the UK, and January 2020 in China. These two questions aimed to understand not only the emotional aspect of their experiences but also the matters they cared about or the objects of their concerns. When analysing their accounts for the second question, particular attention was given to distinguish the lived experiences during virtual learning (i.e., Moment 2) and their overall reflective conclusions or lessons learned from those experiences (i.e., Moment 3). The Moment 2 accounts are, in essence, descriptive, providing participants’ descriptions of what has happened since Moment 1, whereas Moment 3 accounts mirror the outcomes of the lived experiences.

4.1 Emotions

4.1.1 Emotional Reactions at Moment 1

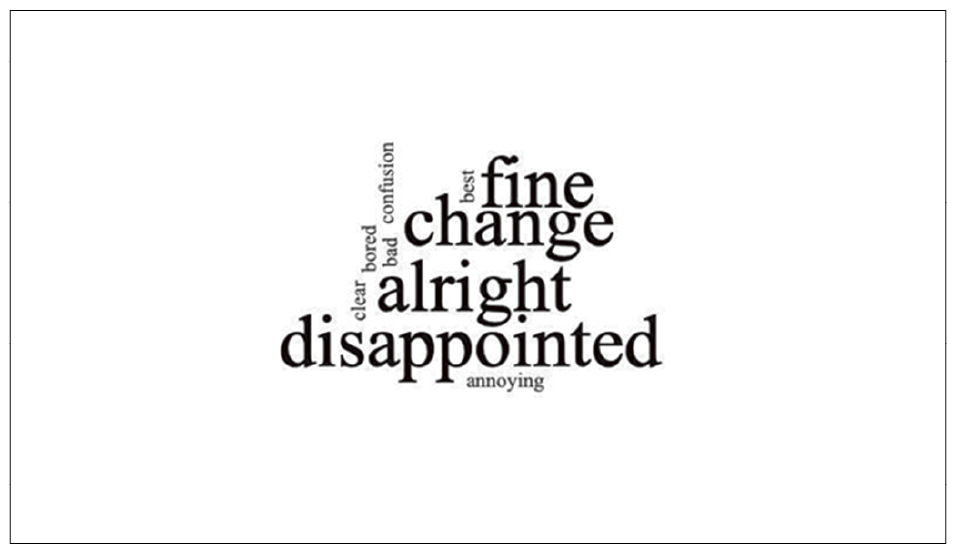

A variety of emotions were experienced by the participants. Figure 2 illustrates the top 10 most frequently used emotional words in the English scripts. ‘Alright’ and ‘fine’ were each mentioned twice among four participant accounts, while ‘disappointed’ was mentioned twice by one participant. The term ‘change’ was referenced twice, but in different contexts: one instance reflected the student’s surprise at the change, while the other indicated the participant did not anticipate a significant change.

|

Figure 2. Top 10 most frequently displayed Moment 1 emotional words in the Ukraine and British samples.

As illustrated in Table 2, the overall emotional status seems to be torn apart between the bipolar spectrum of negativity and positivity. On the negative side, some participants felt uncertain and worried, while others experienced disappointment due to the in-person study year being ‘cut short’ (student BS_E Y2 MC) or the loss of social contact (student BS_C Y1 Sumy4). On the positive side, emotional reactions included ‘新奇’, ‘excited’, ‘great’, and ‘(pleasantly) surprised’. For example, one student said: ‘I was excited … about how weird everything is going to be’ (BS_E Y3 Wom). Excitement, happiness, and curiosity appeared to be predominant among the Chinese participants.

Table 2. All Moment 1 Emotional Words in all Socio-cultural Groups

Negative |

Neutral |

Fairly Positive |

Very Positive |

uncertain / dubious / confused / disoriented (count: 5)

worried / 担心 (count: 4)

disappointed (count: 3)

not clear / unfamiliar (count: 2)

‘不是很想’, ‘想回学校’ (translation: unwilling) (count: 2)

annoying (for study year being cut short) (count: 1)

bad (count: 1)

daunting (count: 1)

sad (count: 1)

sceptical (count: 1) |

didn’t change

a new experience

(feel) strange

wasn’t nervous

open to the idea |

alright / fine / okay (count: 4)

at easy / 放松(count: 2)

I’m prepared

making the best of a bad situation |

新奇 (translation: curious) (count: 8)

excited / 兴奋(count: 6)

great / 高兴 / 开心 / 窃喜 (count: 5)

(pleasantly) surprised (count: 3)

looking forward / 期待 (count: 2)

觉得理直气壮 (translation: feeling confidently and righteously) (count: 1)

|

4.1.2 Emotional Reactions at Moment 2

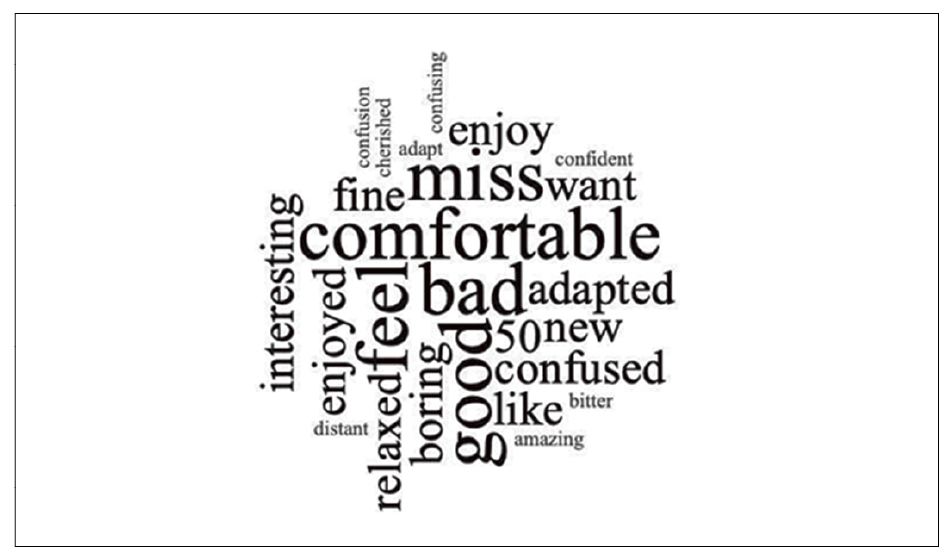

Figure 3 illustrates the top 25 most frequently used Moment 2 emotional words in the Ukraine and British samples. A very similar trajectory was observed in the Chinese dataset as well. The feelings experienced by the participants are diverse; however, there is a clear overall trajectory where their emotions transitioned from ‘confused’, ‘chaotic’, ‘messy’, ‘担心’ (worried), to a sense of ‘getting used to it’ [virtual learning / teaching] or getting ‘easier’, and a sense of it being more ‘enjoyable’, ‘fun’ or ‘好玩’, and ‘有意思’ (interesting) than how they felt at the beginning of the change. The worrying feeling is often associated with the anticipation of performance in assessments, while some Chinese students explicitly expressed emotional struggles in combating idleness and distractions when studying from home. Mixed feelings are demonstrated in expressions, such as ‘50/50’, ‘mixed’, and ‘but … I miss …’. The majority of students felt positive about doing their studies online during the lockdown, as indicated by terms such as ‘not bad’ and ‘good’.

|

Figure 3. Top 25 most frequently displayed Moment 2 emotional words in the Ukraine and UK samples.

4.1.3 Emotional Reactions at Moment 3

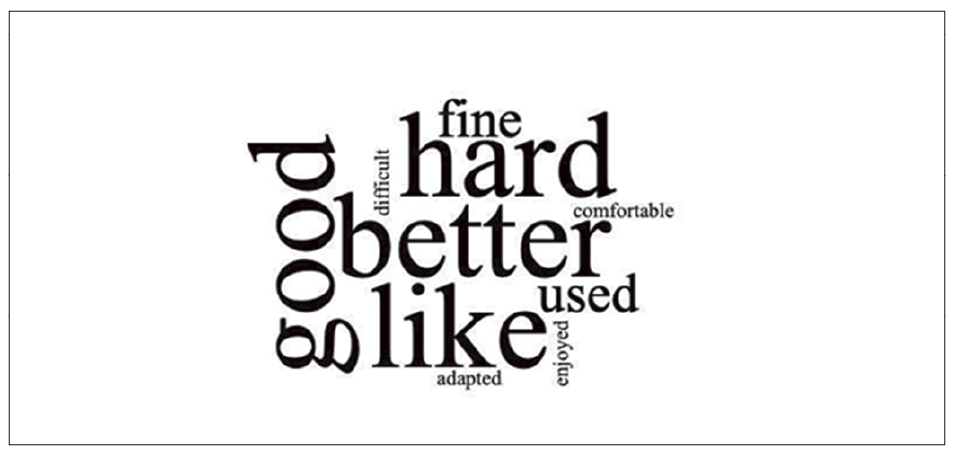

Figure 4 illustrates the top 10 most frequently used emotional terms at Moment 3 in the Ukraine and UK samples. Including the Chinese sample, the Moment 3 emotions predominantly feature positivity. The count for positive feelings i.e. ‘better’/‘更好’, ‘good’/‘很好/好’, ‘like’/‘喜欢’ and ‘fine’ is 23. In contrast, the sense of challenging or negative i.e. ‘hard’, ‘difficult’ , and ‘不好’/‘不太好’/‘困难’ were mentioned 10 times in the data. This numerical discrepancy suggests that the emotional reactions at Moment 3 are largely positive.

Over 80% of the participants explicitly spoke about the positive aspects of virtual learning, such as timesaving or the ability to playback lecture recordings at a convenient time. Examples from the Chinese group include phrases such as ‘网络学习也挺方便’ (translation: online learning is actually quite convenient) (student BS_A Y3 Gang), ‘优点’ (translation: advantages) (student BS_B Y4 G), and ‘非常的便利’ (translation: very convenient) (student BS_B Y4 H).

Some students also felt negative about certain aspects, such as a lack of in-person communication and technological problems. The former is reinforced by a sense of longing to return to how life was before the pandemic, as expressed by many students. For example, student BS_E Y3 RW said; ‘I am looking forward to moving back to normality’ while student BS_C Y1 Sumy8 remarked: ‘I … want to go back to normal learning and live communication’. This longing for a return to normality was realized in China at the time of the interview - All the Chinese students expressed their delight at being able to resume their studies on campus.

|

Figure 4. Top 10 most frequently displayed Moment 3 emotional words in the Ukraine and UK samples.

4.2 The Objects of Concern

The analytical table of objects of concern is provided in the Appendix 1. The analysis reveals that, in descending order of coding frequency, the students’ concerns at Moment 1 were related to their studies, such as lectures, homework, and assessments, their conduct as students, life outside of study, such as their social and family life, the surrounding environment in general, and self-efficacy, such as their information technology literacy. The participants’ Moment 2 accounts cover a great deal of issues captured in 13 coding categories. Based on coding frequencies, the participants most often spoke about their conduct as learners, followed by study-related aspects like lectures, assessments, and resources. Comparisons between online and in-person delivery of lessons, lecturers, social contact, and IT skills were also frequently referred to. Table 3 highlights some examples from the data.

It is worth noting that some students disliked the absence of face-to-face social communication with other students and / or lecturers, thus cherishing or “怀念” (missing) those physical social interactions more. In contrast, some students felt online communication was not “too bad”. For example, student MC remarked: “I didn’t feel too distant from uni … I didn’t feel stuck at home by myself.” Less mentioned issues include “doing uni work from home”, technical issues, the learning environment (e.g., “a learning atmosphere”), time and behaviour (e.g., quickly or slowly adapting to online learning), time and travel (e.g., “I didn’t have to spend time travelling”), work placement, and social contribution.

Table 3. Frequently Referred Objects of Concern at Moment 2

The Objects of Concerns |

Examples from the Data |

student conduct |

“...it was so normal to wake up in the morning and put your camera on, make sure your presence is known to your team” (student BS_E Y3 VH)

“... couldn’t really concentrate on study” (student BS_B Y3 I) |

study |

“... lectures are more structured than it was last year … learning resources are available more rapidly.” (student BS_E Y2 LB)

“Teachers tend to ask more questions in virtual classroom” (student BS_A Y3 Ji) |

online and in-person delivery of teaching |

“It’s good that we get the option to choose, because some people prefer in person, but I enjoyed it being online.” (student BS_E Y2 BI)

“Learning online is not as tiring as taking a lesson in the classroom.” (student BS_A Y3 Wang)

“Online communication is not as clear as in-person communication.” (student BS_B Y3 C) |

social contact |

“... we see each other every meeting, but nobody talks to each other.” (student BS_C Y2 Sumy11)

“Everything became virtual …I don’t have that much human contact.” (student BS_E Y3 VH)

“At the start of every online lesson, the teacher always showed us the outside of his apartment from the balcony … when he returned to Wuhan, he showed us cherry blossoms on campus in the first five minutes of class … when I saw it I felt how much I have missed the time on campus.” (student BS_B Y3 C) |

IT skills |

“No one knew whether to put their cameras on or mics on.” (student BS_E Y3 SK)

“... the tutors and the students were all on the same level, trying to understand the technology.” (student BS_E Y3 Wom) |

At Moment 3, they described their lived experiences as ‘good’ or expressed their liking of some of the things that they had experienced. Some participants expressed their appreciation of the difficult situations or challenges that they faced. One of their main concerns has been their evaluation of online learning and in-person learning, recognising the respective benefits of both modes of study; but more interestingly, the participants reflect upon the past and evaluate what they have gained from these experiences. For example, student BS_E Y2 SK remarked: ‘I didn’t feel like we got less out of the lectures as [sic] we did before … Everyone feels more like they know what they’re doing.’ Likewise, student BS_E Y3 LS said: ‘My grades haven’t suffered at all. It’s working, just getting your head around it.’

4.3 Changes Across the Moments

From Moment 1 to Moment 2, and to Moment 3, the participants have experienced a wide range of emotional reactions as reported above. At Moment 1, emotions were mainly ‘fine’ or ‘excited’ about the new experience that was to come, while accompanied by some uncertainty and worries. At Moment 2, mixed feelings were expressed by the participants. Some of them experienced psychological conditions of ‘confused’, ‘chaotic’, ‘messy’ at the beginning, but things then got ‘easier’, and they eventually felt it was enjoyable and that they were comfortable with the new way of learning. Many students felt positive about learning virtually from home, while four students expressed continuous worries about where this virtual learning would lead them in terms of the learning outcome.

It is worth noting that the longing for normal university study before the pandemic appears significant in Moments 1 and 2. At Moment 1, such desires are often associated with resistance to the change, while at Moment 2, the desires are often expressed as ‘I miss …’, and ‘It [virtual learning] was not bad, but …’. At Moment 3, they also speak of their longing for in-person learning, ‘life before the quarantine … and other people, the conversations, the performances, my usual lifestyle’ (student BS_C Y1 Sumy1). There seems to be a heightened desire for going back to normality along the timeline.

4.4 Cross-cultural Comparative Analysis

It appears that the students have experienced quite similar emotional changes over the course. However, compared with their counterparts, many Chinese students repeatedly cited ‘新奇’ (translation: new and novel) at Moment 1. They were overwhelmed by the new change in a very positive way. The phrase ‘新奇’ carries a sense of curiosity, mystery, and fun. Thus, it is apparent that they felt excited and curious about what was coming their way. They indicated that they felt so because such substantial online learning was not something that they had previously experienced, not to mention this would be done from home with no supervision from the teachers. Thus, they anticipated that the forthcoming experience would be interesting and exciting.

The coding of objects of concern was compared across the cases (see the Appendix 1). An apparent cross-cultural difference among the samples lies in the significant emphasis on student conduct and personal development at Moment 3. This theme was coded in the Chinese scripts 27 times, in contrast to 9 and 2 times in the British and Ukrainian scripts, respectively. Ukrainian student BS_C Y1 Sumy10 commented on her improved adaptive skills to online learning. UK-based students expressed their improved capability to mobilise their understanding to deliver online assessment, while student BS_E Y3 LS realised that ‘without having a proper routine, it can be hard to keep motivated’. Thus, what they have learned from the experiences seems to be specific.

In contrast, data from the Chinese sample suggests a more reflexive reflection of more general aspects of their conduct as learners. For example, some students think ahead by saying, for example, ‘I’d like to be able to watch lessons by outstanding teachers in other institutions … a more diverse learning [“多样化的学习”]’ (student BS_B Y4 G). Many Chinese students commented on their attitude towards study, whether online or offline, self-discipline, and managing time in general.

5 DISCUSSION

The first research objective aimed to investigate emotional responses of students following the launch of full virtual teaching and learning induced by COVID-19. From Moment 1 to Moment 2, and to Moment 3, participants from diverse socio-cultural contexts underwent a wide range of emotions. An overarching emotional trajectory emerged: a combination of ‘fine’ or even ‘excited’ with some worries at Moment 1 → diverse psychological emotions of ‘chaotic’, ‘messy’, ‘adapted’, ‘enjoyable’, ‘worried’, and ‘miss’ at Moment 2 → a retrospective evaluation of experiences as ‘hard’ and ‘difficult, but positive, coupled with forward-looking reflections on future university study that embraces a blended approach at Moment 3.

This trajectory of emotions echoes Schneider and Goldwasser’s change curve, encapsulating phases of expectation, despair, and the emergence of positive perspectives[24]. The observed mixed emotions at Moment 1 underscore the varied expectations students held regarding the forthcoming change. The Chinese students exhibited a comparatively higher level of anticipation, evident in their frequent use of terms like ‘新奇’ (curious), ‘兴奋’ (excited), ‘高兴’ (great / happy), ‘开心’ (happy), and ‘窃喜’ (great / happy) (Table 2) than their counterparts in the UK and Ukraine. Transitioning to Moment 2, students encountered both material and emotional challenges, which mirrors a phase akin to despair, marked by descriptors such as ‘chaotic’, ‘annoyed’, and ‘confused’, Fortunately, many students discovered positive aspects amidst the challenges, fostering a more optimistic outlook on their future development.

The second research objective was to investigate the students’ concerns in their lived experiences. The analysis reveals that the students’ primary concerns at Moment 1 are issues related to lectures, homework, and assessments, which is followed by their considerations of their conduct as students and matters related to their social and family life. Transitioning to Moment 2, the central concern shifted to a critical evaluation of their own conduct as students. At Moment 3, a key focus emerged on reflective and forward-thinking aspects of their personal development. Having navigated the challenges brought about by the changes, students were able to evaluate both virtual education and traditional campus-based provision. A prominent theme was the recognition of advantages and disadvantages in both online and offline teaching / learning. Students expressed a desire for the continuation of certain online teaching functions, such as the ability to replay recorded lectures, while also expressing a longing for in-person interactions with peers and teachers to alleviate concerns about their studies.

The third research objective was to identify commonalities and differences in the experiences of students during the implementation of full virtual teaching induced by COVID-19 across the socio-cultural contexts of China, the UK, and Ukraine. It was observed that, firstly, students underwent similar emotional changes over the period. However, compared with their counterparts, many Chinese students were more overwhelmed by the change in a very positive way at Moment 1. This may be because virtual learning being less widely implemented in China before the outbreak of COVID-19. The pandemic-induced shift to virtual learning introduced novelty to Chinese university students[6] and opened up new possibilities for higher education in China[4].

Secondly, all participants have articulated their learning from the lived experiences in terms of shaping their future study pursuits. Many Chinese students reflected on their attitude toward study, whether online or offline, and emphasized the importance of self-discipline. On the other hand, accounts from some students from English and Ukrainian socio-cultural backgrounds seemed to reflect more specific and immediate learning needs, such as acquiring online learning skills, skills to handle online assessments, and better appreciation of having ‘a proper routine’ to deliver good performance. However, caution is warranted when interpreting observed differences: (1) While Li and Rivers[61] suggest that deep and continuous reflexive thinking [悟 wù] is rooted in Chinese culture which influences how Chinese students learn, and Sun and Richardson[62] claim that Chinese students were less likely to exhibit deep or strategic approaches to studying than British students, there is insufficient evidence to suggest that students in Confucian societies engage in more deep learning than those in the West or vice versa[63]. (2) It is evident that reflexivity is an area of research that is often overlooked in educational research. Mills et al.[64] report that emotion and reflexivity are connected in cultural learning, but this connection is not further examined or explained. Human reflexivity involves inward internal dialogue that can lead to deep and critical thinking, evaluations of concerns, and considerations of life chances; thus, it plays a critical role in explaining deep learning, or the lack thereof. In the present study, reflexivity, emotion, and learning are elucidated through the theoretical framing of emotion being related to the things that students care about or the objects of concern.

Thirdly, there is a commonly shared desire to return to normality among all the participants. At Moment 1, some students were ‘skeptical’ about virtual learning and expressed concerns about not being able to have in-person interactions with their fellow students and teachers. A couple of Chinese students softly expressed their rejection to pure online learning by saying ‘想回学校’ (translation: want to go back to the campus) (student BS_B Y2 D). In the phase of Moment 2, more students have shown their inclination of looking for things that were missing, which is apparent in their use of terms such as ‘good … but’ and ‘missing’/‘怀念’. Such an inclination becomes more apparent among further participants in their Moment 3 accounts, expressing a longing for in-person learning and a return to the ‘life before the quarantine’ (student BS_C Y1 Sumy1). This reflects an enhanced, positive attitude to campus-based study - valuing the ‘normal learning’ [as described by some participants] in university education. This finding aligns with what Li and Rivers[61] have reported, emphasizing that positive values related to learning and education encourage enhanced learning outcomes.

More interestingly, their words echo the realist position about change and absence, whereby change is seen as a mode of absence / absenting[23]. This also affirms Bhaskar’s argument that absence is the “heart of existence”[24]. At Moments 2 and 3, the participants expressed their desire to regain in-person social contact and the normal daily routines they had before the pandemic, expressing hope for a future university education. Such expressions reflect their hope for future university education, which indeed further reinforces that absenting is the ‘hub of space, time, and causality’[24], and that absence forms reasons for acting through the bases of knowledge / beliefs, desire, hope, being expressed, and practicality[23].

6 IMPLICATIONS FOR EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE AND RESEARCH

6.1 Evidence-based Practice

In the realist perspective, events are caused by generative powers of structure and agency. These students’ lived experiences are not reducible to them as individuals but jointly shaped or emerged from the interplay between structure and agency. The pandemic induced implication of full virtual teaching, which was given to them who reacted to it and who have also changed / developed as individuals as a result of the experiences. The pandemic is a context within which the change of teaching mode or intervention was ‘imposed’ on the students, assuming every one of them has equal access to social and material resources, such as a suitable environment for learning from home and necessary technologies to continue their study ‘as normal’. The participants’ accounts have revealed their struggle and their ability or power to handle the change that was given to them, which may echo what other university students have also experienced. Thus, the findings of this study provide evidence that sheds light on evidence-based practice aimed at enhancing university students’ learning and their university lives.

Thus, it is argued that university policies and strategies need to be positioned to fulfil the absent, not blindly, but in a way that provides individually catered emotional, social, and study support for the students. It should be acknowledged that not all students have equal access to social and material resources, nor do they share the same way of dealing with changes emotionally and cognitively. More specifically, to establish a better, socially equitable structural platform, provisions such as a student well-being service or a professionally-led social online / offline forum are necessary. These can provide a channel for students to get help with their affective struggles or reactions to changes in study and other issues that can affect their study and wellbeing.

Furthermore, as seen in this study, sample students appreciate the benefits of both virtual learning and face-to-face interactions with their fellow students and lecturers in physical university settings. This aligns with the finding that suggests an enhanced, positive attitude toward campus-based study at Moment 3. Thus, university education should leverage technological advances in the delivery of teaching and support of students’ learning. This should be coupled with a continuous emphasis on embedding ‘the personal element’ or in-person social interactions in teaching to better support online provision. Lastly, our data shows that the sampled Chinese students seem to be more concerned about their long-term gains than immediate returns from their education. Thus, marketing efforts to attract Chinese students should not only address the absent but also highlight the opportunities for personal development in a broader sense. This means focusing on not only university life and transferable skills (cognitive development) but also one’s development as a human being (intellectual and moral development).

6.2 Research

Reflecting upon the findings related to the first and second research questions prompts further consideration of theoretical and methodological aspects related to the exploration of “emotion” as a central focus of research. Theoretically, the psychological community lacks a unanimous definition of emotion; however, there is a consensus that emotions and forms of thought are distinct entities, influencing decision-making and action[20,28,29]. Sociologists such as Archer[21], Nussbaum[31] and Sayer[32], argue that emotions are inherently relational, connected to something external. It is felt that the realist conceptualisation of emotions is helpful in effort to examine emotions.

Methodologically, the analytical dualism of emotion (i.e., separating the feeling from the object of that feeling) facilitates the deconstruction of emotions, enabling the subsequent reintegration of these two dimensions. This separation allows for the nuanced exploration of emerging feelings and elements perceived important to the students. The subsequent rejoining of these dimensions aids in comprehending the actual meanings of the emotions experienced. A pivotal concern arises, however, as the research heavily relies on words, which may fall short in adequately capturing people’s emotions. As Dixon[29] has pointed out, emotion is a dynamic cognitive process, with changes manifesting through facial expressions or body language, surpassing the limitations of verbal expression.

7 CONCLUSION AND LIMITATIONS

This paper reported the experiences of undergraduate business management students in China, the UK, and Ukraine. It discovered that (1) participants from diverse socio-cultural contexts have experienced a wide range of emotions, indicating an overall trajectory of emotional changes; (2) the students’ primary concerns change as situations progress, transitioning from study-related concerns at Moment 1 to evaluative concerns about their conduct as students at Moment 2, and finally to the evaluation of the outcomes at Moment 3; (3) Additionally, the students shared a collective desire to return to normality, with the desire to return to campus is present at the beginning of the full implementation of virtual teaching and grows stronger as time moves on; and (4) compared with their counterparts from English and Ukrainian backgrounds, a significant number of Chinese students exhibited a particularly positive response to the change at Moment 1. Furthermore, by Moment 3, their anticipatory reflections extend beyond pragmatism (such as the benefits of blended learning and online skills) to a ‘meta-level’ perspective, encompassing their attitude towards study and recognising the importance of self-discipline. In summary, the study concludes that emotions, reflexivity, absent, and absenting are integral factors that shape student experiences.

The limitations of this study are primarily methodological. The main methodological challenges were: (1) in-person interview was not possible for all the cases due to COVID-19 restrictions and / or geographical reasons, (2) not all the interviews were audio recorded, (3) more critically, there is a lack of a toolkit to capture non-verbal emotions. Interviews conducted in Ukraine were translated into English for data analysis; as such, some data were lost during that process. The use of Google Meet and Google Docs enabled interviewees to type their responses in real-time during online interviews, representing an innovative way to conduct synchronous, online, written interviews[51]. However, our experience with this approach in this project raises questions about the depth of data it can generate when compared to the conventional procedure of recording and transcribing. Our observation, evident in the Appendix 1 where coding in the UK dataset was less intensive than in the Chinese data collected through the conventional procedure, suggests that the latter is more effective and fruitful. As such, we are cautious about drawing a conclusion about any comparisons and interpreting identified cross-cultural differences. However, the overall research approach adopted in this study has allowed international research collaborations and provided the team with valuable insights from the three socio-cultural contexts. It has also proved that the conventional interview procedures worked well in this project, allowing rich data to be collected and shared in the team.

Acknowledgements

The research team would like to thank Bo Li and Qiong Zou for their assistance with data collection in China, and Andrii Witrenko and Konstantin Kyrychenko for their contributions in collecting data in Ukraine.

Ethics Approval Statement

This research was approved by the Ethics Peer Review College, Bath Spa University, UK, on the 3rd of August 2020. Approval number: 290520LL.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Author Contribution

Li L, Liu L, Opara V, Pomorina I, and Walker A designed the study. Li L performed the data analysis. Li L drafted the manuscript. Li L, Liu L, Wang J, Pomorina I, and Walker A revised the manuscript. All the authors contributed to writing the article, read, and approved its submission.

Abbreviation List

BSs, Business schools

HEIs, Higher educational institutions

References

[1] Goedegebuure L, Meek L. Crisis - What Crisis? Stud High Educ, 2021; 46: 1-4.[DOI]

[2] Clark S, Gallagher E, Boyle N et al. The international education index: A global approach to education policy analysis, performance and sustainable development. Brit Educ Res J, 2023; 49: 266-287.[DOI]

[3] Perrotta D. Universities and Covid-19 in Argentina: From community engagement to regulation. Stud High Educ, 2021; 46: 30-43.[DOI]

[4] Yang B, Huang C. Turn crisis into opportunity in response to COVID-19: Experience from a Chinese university and future prospects. Stud High Educ, 2021; 46: 121-132.[DOI]

[5] Coates H, Xie Z, Hong X. Engaging transformed fundamentals to design global hybrid higher education. Stud High Educ, 2021; 46: 166-176.[DOI]

[6] Poole A, Bunnell T. Precarious privilege in the time of pandemic: A hybrid (auto) ethnographic perspective on COVID-19 and international schooling in China. Brit Educ Res J, 2022; 48: 915-931.[DOI]

[7] Hoskins K, Thu T, Xu Y et al. Me, my child and Covid-19: Parents' reflections on their child's experiences of lockdown in the UK and China. Brit Educ Res J, 2023; 49: 455-475.[DOI]

[8] De Boer H. COVID-19 in Dutch higher education. Stud High Educ, 2021; 46: 96-106.[DOI]

[9] Le AT. Support for doctoral candidates in Australia during the pandemic: The case of the University of Melbourne. Stud High Educ, 2021; 46: 133-145.[DOI]

[10] Bartolic S, Matzat U, Tai J et al. Student vulnerabilities and confidence in learning in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Stud High Educ, 2022; 47: 2460-2472.[DOI]

[11] Agasisti T, Soncin M. Higher education in troubled times: On the impact of COVID-19 in Italy. Stud High Educ, 2021; 46: 86-95.[DOI]

[12] Betts A. A lockdown journal from Catalonia. Stud High Educ, 2021; 46: 75-85.[DOI]

[13] Archer MS. Realist Social Theory: The Morphogenetic Approach. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995.

[14] Archer MS. Culture and Agency: The Place of Culture in Social Theory. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996.

[15] O’Brien M. Theorising modernity: Reflexivity, identity and environment in Giddens. In: Theorising Modernity. Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1999; 17-38.

[16] Giddens A. The Consequences of Modernity. Polity Press in Association with Blackwell: Cambridge, UK, 1990.

[17] Maclean M, Harvey C, Chia R. Reflexive practice and the making of elite business careers. Manage Learn, 2012; 43: 385-404.[DOI]

[18] Archer MS. Making our way through the world: Human reflexivity and social mobility. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007.

[19] Archer MS. The Reflexive Imperative in Late Modernity. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012.

[20] Taylor C, Charles T. Philosophical papers: Human agency and language. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1985.

[21] Archer MS. Being Human: The Problem of Agency. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000.

[22] Popper K. Knowledge and the Body-mind Problem: In Defence of Interaction. Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013.

[23] Hartwig M. Dictionary of Critical Realism. Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015.

[24] Bhaskar R. Plato etc: Problems of Philosophy and Their Resolution. Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2009.

[25] Schneider DM, Goldwasser C. Be a model leader of change. Manage Rev, 1998; 87: 41-45.

[26] Liu L, Li L, Pomorina I et al. What do business students value in the emerging virtualisation of learning and teaching that is accelerated by COVID-19? A pilot study of the business students at Bath Spa University. Developments in Economics Education Conference, 2021.

[27] Izard CE. The many meanings / aspects of emotion: Definitions, functions, activation, and regulation. Emot Rev, 2010; 2: 363-370.[DOI]

[28] Dixon T. Reolting Passions. Mod Theol, 2011; 27: 298-312.[DOI]

[29] Dixon T. “Emotion”: The history of a keyword in crisis. Emot Rev, 2012; 4: 338-344.[DOI]

[30] Archer MS. Structure, Agency and the Internal Conversation. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003.

[31] Nussbaum MC. Upheavals of Thought: The Intelligence of Emotions. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003.

[32] Sayer A. Why Things Matter to People: Social Science, Values, and Ethical Life. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011.

[33] Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of moral thought and action. In: Handbook of Moral Behavior and Development. Psychology press: New York, USA, 2014; 69-128.

[34] Craib I. Experiencing Identity. Sage: London, UK, 1998.

[35] Oakley J. Morality and Emotions. Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1992.

[36] Lv J, Yang J. Prediction of college students’ classroom learning effect considering positive learning emotion. Int J Emerg Technol, 2023; 18: 161-174.[DOI]

[37] Wang C. Emotion recognition of college students’ online learning engagement based on deep learning. Int J Emerg Technol, 2022; 17: 110-122.[DOI]

[38] Wang Y, Cao Y, Gong S et al. Interaction and learning engagement in online learning: The mediating roles of online learning self-efficacy and academic emotions. Learn Individ Differ, 2022; 94: 102128.[DOI]

[39] Wu Y, Xu X, Xue J et al. A cross-group comparison study of the effect of interaction on satisfaction in online learning: The parallel mediating role of academic emotions and self-regulated learning. Comput Educ, 2023; 199: 104776.[DOI]

[40] Wen L. Influence of emotional interaction on learners’ knowledge construction in online collaboration mode. Int J Emerg Technol, 2022; 17: 76-92.[DOI]

[41] Berweger B, Born S, Dietrich J. Expectancy-value appraisals and achievement emotions in an online learning environment: Within- and between-person relationships. Learn Instr, 2022; 77: 101546.[DOI]

[42] Cheng S, Huang JC, Hebert W. Profiles of vocational college students’ achievement emotions in online learning environments: Antecedents and outcomes. Comput Hum Behav, 2023; 138: 107452.[DOI]

[43] Pekrun R. The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educ Psychol Rev, 2006; 18: 315-341.[DOI]

[44] Shao K, Kutuk G, Fryer LK et al. Factors influencing Chinese undergraduate students’ emotions in an online EFL learning context during the COVID pandemic. J Comput Assist Lear, 2021; 39: 1465-1478.[DOI]

[45] Archer MS. Generative Mechanisms Transforming the Social Order. Spring: London, UK, 2015.

[46] Francis JJ, Johnston M, Robertson C et al. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol Health, 2010; 25: 1229-1245.[DOI]

[47] Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Method, 2006; 18: 59-82.[DOI]

[48] Saunders MNK, Townsend K. Reporting and justifying the number of interview participants in organization and workplace research. Brit J Manage, 2016; 27: 836-852.[DOI]

[49] O’Reilly M, Parker N. ‘Unsatisfactory Saturation’: a critical exploration of the notion of saturated sample sizes in qualitative research. Qual Res, 2013; 13: 190-197.[DOI]

[50] Yin RK. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Sage: London, UK, 2003.

[51] Opara V. Spangsdorf S, Ryan MK. Reflecting on the use of Google Docs for online interviews: Innovation in qualitative data collection. Qual Res, 2023; 23: 561-578.[DOI]

[52] Ritchie J, Spencer L, O’Connor W. Carrying out qualitative analysis. In: Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers. Sage: London, UK, 2003; 2003: 219-262.

[53] Hsieh S, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res, 2005; 15: 1277-1288.[DOI]

[54] Nicolini D. Zooming in and out: Study practices by switching theoretical lenses and trailing connections. Organ Stud, 2009; 30: 1391-1418.[DOI]

[55] Danermark B, Ekström M, Karlsson JC. Explaining Society: Critical Realism in the Social Sciences. Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019.

[56] Sayer RA. Method in Social Science. A Realist Approach. Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1992.

[57] Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. Sage: London, UK, 2005.

[58] Denzin NK. The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods. Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017.

[59] Bhaskar R. Reclaiming Reality: A Critical Introduction to Contemporary Philosophy. Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2010.[DOI]

[60] Li L. Critical realist approach: A solution to tourism’s most pressing matter. Curr Issues Tour, 2022; 25: 1541-1556.[DOI]

[61] Li L, Rivers GJ. An inquiry into the delivering of a British curriculum in China. Teach High Educ, 2018; 23: 785-801.[DOI]

[62] Sun H, Richardson JTE. Perceptions of quality and approaches to studying in higher education: A comparative study of Chinese and British postgraduate students at six British business schools. High Educ, 2012; 63: 299-316.[DOI]

[63] Biggs JB. Western misperceptions of the Confucian heritage learning culture. In: The Chinese Learner: Cultural, Psychological and Contextual Influences. University of Hong Kong, Comparative Education Research Centre: Hong Kong, China, 1996; 45-67.

[64] Mills K, Creedy DK, Sunderland N et al. Evaluation of a first peoples-led, emotion-based pedagogical intervention to promote cultural safety in undergraduate non-Indigenous health professional students. Nurs Educ Today, 2022; 109: 105219.[DOI]

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). This open-access article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Copyright ©

Copyright ©