Characterization of Colletotrichum Species as Causal Agents of Anthracnose in Strawberry Productive Areas in Tucumán, Argentina

Sergio M Salazar1,2*, Sebastián N Moschen1,3, Marta E Arias4,5, Ramiro N Furio1,3, Atilio P Castagnaro6, Juan C Díaz Ricci6

1Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria (INTA), Estación Experimental Agropecuaria Famaillá, Tucumán, Argentina

2Universidad Nacional de Tucumán (UNT), Facultad de Agronomía y Zootecnia, Tucumán, Argentina

3Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), Buenos Aires, Argentina

4Universidad Nacional de Tucumán (UNT), Facultad de Ciencias Naturales e Instituto Miguel Lillo, Tucumán, Argentina

5Centro Regional de Energía y Ambiente para el desarrollo Sustentable (CREAS), Universidad Nacional de Catamarca, Catamarca, Argentina

6Instituto Superior de Investigaciones Biológicas (INSIBIO). CONICET, UNT and Instituto de Química Biológica “Dr. Bernabé Bloj”, Facultad de Bioquímica, Química y Farmacia, Universidad Nacional de Tucumán, Tucumán, Argentina

*Correspondence to: Sergio M Salazar, PhD, Lecturer, Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria (INTA), Estación Experimental Agropecuaria Famaillá, Ruta Provincial 301km 32, Famaillá, Tucumán 4132, Argentina; Email: salazar.sergio@inta.gob.ar

Abstract

Objective: Anthracnose is a disease caused by Colletotrichum species and is a significant disease in the strawberry crop. This study aims to identify at the level of species Colletotrichum spp. isolates collected from symptomatic strawberry plants in Tucumán, Argentina's second most important strawberry production area.

Methods: 45 isolates of Colletotrichum were collected and characterized. Morphological characterization was conducted by analyzing fungal cultural characteristics, the growth rate in potato dextrose agar plates, conidial morphology and size, and sexual state. Phytopathological characterization was carried out by plant-pathogen interactions under controlled conditions in infection chambers. Molecular characterization was performed by polymerase chain reaction analysis of regions of amplified mitochondrial small rRNA genes.

Results: Preliminary morphological characterization led to three distinctive groups, based on conidial shape and size, and colony type, colour, and growth, whereas the phytopathological characterization, led to two distinct groups based on the severity of symptoms, virulence, and host specificity. Molecular analyses confirmed the identity of three isolates representing each of the microbiological groups (i.e., isolate F7 of Colletotrichum acutatum (C. acutatum), isolate L9 of C. acutatum, isolate M11 of C. acutatum), demonstrating that they correspond to C. acutatum species. Based on the analysis of ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacers sequences, and using specific microsatellites, we found a high genetic variability among all C. acutatum sequences. Implications of these results, as well as biological products commercially available and research advancing the field of biological control agents, were also discussed.

Conclusion: This is the latest study to report with confidence that the species of Colletotrichum present in Tucumán, Argentina corresponds to C. acutatum, and such species are genetically diverse.

Keywords: Colletotrichum, anthracnose, strawberry, Fragaria x ananassa, biological control agents

1 INTRODUCTION

Colletotrichum species is the causal agent of anthracnose, affecting a wide range of plants and crops with high agronomical value worldwide[1-4]. The Colletotrichum acutatum (C. acutatum) species complex is known as especially destructive on fruits such as strawberry[5-7], apple[8-11], citrus[12-16], olive[17-21], cranberry[22,23], blueberry[24-27] and peach[28].

Anthracnose disease, also known as black spot, fruit rot, or crown rot, is one of the most important diseases affecting the strawberry crop[29]. The term "anthracnose", was initially used to describe a new disease of strawberries caused by Colletotrichum fragariae (C. fragariae)[30], but was later generalized and used to refer to all diseases caused by fungi that belong to the Colletotrichum species[31,32]. These pathogens can attack crowns, leaves (petioles and leaflets), peduncles, pedicels, fruits, flowers, buds, runners and roots[33-35]. There are three species of Colletotrichum known as the etiological agents of anthracnose disease in strawberry crops: C. acutatum J.H. Simmonds, C. fragariae Brooks, and Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (C. gloeosporioides) (Penz.) Penz. and Sacc. in Penz. (Teleomorph Glomerella cingulata (G. cingulata) (Stoneman) Spauld. & H. Schrenk)[32,34,36-38].

The Colletotrichum species is a complex and confusing genus that has undergone various taxonomic revisions in the last years[1,3,39]. Traditionally, the Colletotrichum species has been characterized mainly based on phenotypical features, by analysing the colony colour and morphology, conidia size and shape, presence of setae, and the existence of the teleomorph Glomerella ciculata and G. cingulata[2,32,33,40]. However, morphological analyses alone are insufficiently informative because these characters can be influenced by environmental conditions - such as the culture media, light, and temperature, leading to ambiguous determinations[41-43]. Therefore, molecular analysis has been incorporated because it allows for precise discrimination among Colletotrichum species[1,44-48]. Currently, the polyphasic approach is the most precise methodology used to characterize Colletotrichum species; it involves the evaluation of both morphological features and DNA sequences such as the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) ribosomal DNA (rDNA).

Strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa Duch.) is a highly valued fruit worldwide due to its nutritive and nutraceutical features. Argentina is the third-largest producer of strawberries in South America, with approximately 1,300 hectares and a production of around 45,500 tons per year[49]. The provinces of Santa Fe, Tucumán, and Buenos Aires concentrate around 70% of the country's total production of strawberries, with Tucumán as the second most productive area of Argentina[49].

Anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum spp. is a serious threat to strawberry production, especially in warm and humid climates, such as those encountered in Tucumán, Argentina[34]. Therefore, to implement the correct disease control methods, it is necessary to first determine which species of Colletotrichum are currently present in the strawberry productive area of interest. Few studies were performed to screen the Colletotrichum species present in Tucumán, Argentina[50-52] and revealed that approximately 80% of the etiological agents corresponded to C. fragariae, 19% to C. acutatum, and to a much lesser extent to C. gloeosporioides. However, such information is no longer reliable because of two main reasons. Firstly, those studies were based solely on phenotypical characterization; secondly, the composition of pathogen populations present in the soil may change over time, and those studies were performed more than two decades ago. Therefore, this study aims to perform an assessment of Colletotrichum species present in the crop area of Tucumán, Argentina. Results revealed that C. acutatum is the predominant species in the region, presenting a broad microbial, phytopathological and genetic diversity.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Obtention of the Fungal Isolates, Propagation, and Maintenance

Fungal isolates were obtained from the crown of strawberry plants and pre-harvested fruits of the cultivars “Pájaro”, “Chandler” and “Sweet Charlie” cultivated in three productive areas of Tucumán, Argentina, namely, Lules (L), Famaillá (F) and El Manantial (M), that presented symptoms of disease compatible to anthracnose. Isolations were performed on a potato dextrose agar (PDA) supplemented with streptomycin (300mg/mL) and incubated at 28°C under continuous fluorescent light for 10 days[32]. After the incubation, each isolate was single-spore propagated to obtain pure cultures following the needle method[53], and thereafter maintained on PDA slants at 4°C.

2.1 Conidial Suspensions

Fungal isolates were grown on PDA in Petri dishes at 28°C under continuous fluorescent light for 10 days to induce conidia formation. The fungal culture surface was gently scraped with a Pasteur pipette to remove conidia and suspended in sterile distilled water. Then, conidial suspensions were filtered through gauze under axenic conditions to remove mycelial debris. Suspensions were then diluted with sterile distilled to a final concentration of 1.5×106conidia/mL, and used for morphological characterization. For phytopathological assays, Tween 20 was added to the conidial suspensions (2drops/L).

2.2 Staining of Colletotrichum Hyphae

Fungal hyphae and dead leaves of the cultivar (cv.) ‘Pájaro’ were stained by boiling infected leaves for 5min in a solution of ethanolic lactophenol trypan blue. Then, the stained leaves were cleared in chloral hydrate (2.5g/mL) at room temperature by gentle shaking until no more coloured solution emerged. Then, the leaves were imbibed in glycerol 20% for 1h and observed using an optic microscope (BH-2, Olympus, Japan).

2.3 Morphological Characterization of the Fungal Isolates

2.3.1 Cultural Characteristics and Growth Rate

Fungal cultures were grown by transferring a 4mm diameter mycelium plug from a fresh PDA culture to a new PDA contained in a 90mm diameter Petri plate. Cultures were incubated at 28°C for 12 days under continuous fluorescent light[32]. Three replicate plates were prepared for each isolate, and the measures were performed using the best-grown plate after 12 days of incubation.

2.3.2 Conidial Morphology and Size Determination

To determine the conidia morphology and size of each fungal isolate, conidial suspensions were prepared by scraping freshly grown plates. These plates were previously grown on PDA at 28°C under continuous fluorescent light for 10 days to induce conidia formation, and suspended in sterile distilled water at a final concentration of 1.5×106conidia/mL. For morphological determination, 100 conidia were randomly chosen and analysed under an optic microscope (BH-2, Olympus, Japan). For size determination, 25 conidia were randomly chosen, and the length and width were measured under Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM; JSM-35, JEOL, Japan), and expressed as an average.

2.3.3 Sexual State Determination

Perithecia formation was examined in the fungal cultures of each isolate during their growth on a PDA medium at 28°C under continuous fluorescent light, once a week, for two months[40,51,54].

2.4 Molecular Identification of the Fungal Isolates

The molecular characterization was carried out by Commonwealth Mycological Institute (CABI) BioScience (International Mycology Institute, UK Centre, Egham, England). DNA from each isolate was extracted according to Sreenivasaprasad et al.[44] and Buddie et al[48]. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay was performed using specific primers for Colletotrichum species. The primers used to amplify a region of the small rRNA mitochondrial gene of ascomycetes are (from 5´ to 3´): NMS1 (forward: CAGCAGTGAGGAATATTGGTCAATG) and NMS2 (reverse: GCGGATCATCGAATTAAATAACAT)[55], which have been proven to distinguish the Colletotrichum species (Buddie, CABI BioScience, personal communication). The single arbitrary primers (CAG)5 (CAGCAGCAGCAGCAG) and (GACA)4 (GACAGACAGACAGACA) were obtained from minisatellites[46], whilst the primers CaInt2 (forward: GGGGAAGCCTCTCGCGG) from the internally transcribed spacer region of the nuclear ribosomal DNA region of C. acutatum[44] and ITS4 (reverse: TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC) from the nuclear rDNA[56]. Control experiments were performed with DNA from previously identified and characterized C. acutatum, C. fragariae, C. gloeosporioides, Colletotrichum coccodes and other species available at International Mycology Institute (CABI, England). The PCR reactions and the amplification programs used were similar to that reported by Li et al.[55] for NMS1/NMS2, Freeman and Rodriguez[46] for (CAG)5/(GACA)4, and Sreenivasaprasad et al.[44] for CaInt2/ITS4. The PCR was carried out using the Pegasus Taq enzyme (APBiotech, USA), the PCR products were analyzed in a 2% agarose gel, and the bands were visualized upon staining with bromide ethidium.

2.5 Strawberry Plants Maintenance

Fragaria x ananassa strawberry plants of the cultivars 'Pájaro', 'Chandler', 'Sweet Charlie', 'Enzed Donna', 'Oso Grande', 'Selva', 'Camarosa', 'Rosalinda' and 'Gaviota' were used for the phytopathological assays. They were purchased as dormant crowns from commercial nurseries, planted in 8cm pots filled with a pasteurized substrate (humus:perlome, 2:1), and grown in a greenhouse for 6 weeks. Thereafter, grown plants were evaluated to be anthracnose free to serve as the mother plants for agamic propagation. Runners of each cultivar were rooted in a similar pasteurized substrate as described above, under axenic conditions, and maintained in growth chambers at 28°C, 70% RH with a light cycle of 16h per day, for 14 to 16 weeks. Plants were watered every other day with 50mL of sterile distilled water. All senescent leaves and petioles were removed periodically until 10 days before the phytopathological assays, leaving only three unfolded healthy shoots per plant prior to the assay.

2.6 Phytopathological Assays

Phytopathological assays between the different strawberry cultivars and the Colletotrichum isolates were conducted. Cultivars 'Pájaro', 'Chandler', and 'Sweet Charlie' were used as reference genotypes of strawberries and challenged towards all the fungal isolates. Whereas cultivars 'Enzed Donna', 'Oso Grande', 'Selva', 'Camarosa', 'Rosalinda', and 'Gaviota' were also tested against the fungal isolates isolate F7 of C. acutatum (F7) and isolate M11 of C. acutatum (M11). The experimental design was randomized with 8 plants per genotype and the experimental unit. Four plants of each cultivar were sprayed with a conidial suspension of the correspondent isolate (1.5×106conidia/mL) until run-off. In addition, four plants were used as controls and sprayed with sterile distilled water until run-off. Immediately after inoculation, plants were placed in infection chambers at 28-30°C, with 100% RH for 48h in the dark. Then, plants were transferred to growth chambers to assess disease symptoms and severity. Phytopathological assays were repeated twice under identical experimental conditions.

To check pathogen identity, after 50 days post-infection (dpi), isolations from crowns of those plants that developed the disease were performed and compared with the strains initially used for the inoculations.

2.6.1 Disease Severity Rating (DSR)

The DSR was evaluated at 50dpi and scored on a scale ranging from 1 to 5, using a disease index based on petiole symptoms (lesion length and extent), according to Delp and Milholland[31]. A score of 1 denotes a healthy petiole (no lesion); 2 denotes petioles with lesions <3mm; 3 denotes lesions of 3-10mm; 4 denotes lesions of 10-20mm with girdling petiole; 5 denotes an entirely necrotic petiole, equivalent to a dead plant. Plants with a DSR >3 were considered susceptible.

2.7 Statistical Analyses

Data from microbiological and phytopathological assays were analysed using InfoStat software[57]. ANOVA analyses were performed to detect significant variances, followed by the Tukey test at a 95% confidence level[58,59].

3 RESULTS

3.1 Microbiological Characterization of Colletotrichum Isolates

More than 200 fungal isolates were obtained from the crowns and fruits of strawberry plants collected in three different productive locations in Tucumán, Argentina. They were initially characterized as Colletotrichum spp. because plants presented symptoms compatible with anthracnose. A preliminary screening was performed according to whether any distinguishable macro or microscopic difference was observed among the isolates, which allowed the selection of 45 isolates. Considering the geographical location of the collection of these isolates, we first classified them into three groups, viz. L, F and M. L, F and M, followed by the numbering of their isolation order (Table 1).

Table 1. Microbiological and Phytopathological Characteristics of 45 Isolates of Colletotrichum from the Main Strawberry Production Area in Tucumán, Argentina

Isolate N° |

Locationa |

Conidialb Shape |

Colonyc Colour |

Colony d Diameter |

Ascigerouse State |

M-Groupf |

DSR Pájaro |

DSR Chandler |

DSR Sweet Charlie |

P-Groupg |

L4 |

L |

Cylindrical-1 |

C1 |

8.3 |

- |

1 |

1.2 ± |

4.5 ± |

1.9 ± |

1 |

L6 |

L |

Cylindrical-1 |

C1 |

7.9 |

- |

1 |

1.5 ± |

4.8 ± |

1.8 ± |

1 |

L12 |

L |

Cylindrical-1 |

C1 |

7.5 |

- |

1 |

2.0 ± |

4.7 ± |

1.4 ± |

1 |

F1 |

F |

Cylindrical-1 |

C1 |

8.2 |

- |

1 |

1.8 ± |

4.0 ± |

1.6 ± |

1 |

F7* |

F |

Cylindrical-1 |

C1 |

7.4 |

- |

1 |

1.0 ± |

5.0 ± |

1.8 ± |

1 |

F11 |

F |

Cylindrical-1 |

C1 |

8.0 |

- |

1 |

1.0 ± |

3.2 ± |

2.1 ± |

1 |

5 |

M |

Cylindrical-1 |

C1 |

7.2 |

- |

1 |

1.1 ± |

3.5 ± |

2.4 ± |

1 |

M3 |

M |

Cylindrical-1 |

C1 |

7.0 |

- |

1 |

1.4 ± |

4.8 ± |

1.9 ± |

1 |

M15 |

M |

Cylindrical-1 |

C1 |

8.1 |

- |

1 |

1.2 ± |

4.1 ± |

1.9 ± |

1 |

M23 |

M |

Cylindrical-1 |

C1 |

8.9 |

- |

1 |

1.1 ± |

4.6 ± |

2.0 ± |

1 |

L21 |

L |

Cylindrical-1 |

C2 |

4.1 |

- |

2 |

5.0 ± |

1.4 ± |

1.5 ± |

2 |

L11 |

L |

Cylindrical-1 |

C2 |

3.5 |

- |

2 |

4.8 ± |

1.7 ± |

1.8 ± |

2 |

L5 |

L |

Cylindrical-1 |

C2 |

3.2 |

- |

2 |

4.7 ± |

2.3 ± |

2.1 ± |

2 |

L9* |

L |

Cylindrical-1 |

C2 |

4.6 |

- |

2 |

5.0 ± |

2.4 ± |

2.4 ± |

2 |

L2 |

L |

Fusiform |

C3 |

6.8 |

- |

3 |

5.0 ± |

1.2 ± |

1.2 ± |

2 |

L3 |

L |

Fusiform |

C3 |

6.5 |

- |

3 |

5.0 ± |

1.5 ± |

1.6 ± |

2 |

L21 |

L |

Fusiform |

C3 |

6.3 |

- |

3 |

4.5 ± |

1.6 ± |

1.5 ± |

2 |

L32 |

L |

Fusiform |

C3 |

7.1 |

- |

3 |

4.8 ± |

2.0 ± |

1.0 ± |

2 |

L27 |

L |

Fusiform |

C3 |

7.9 |

- |

3 |

5.0 ± |

2.3 ± |

1.2 ± |

2 |

L41 |

L |

Fusiform |

C3 |

6.5 |

- |

3 |

4.0 ± |

2.5 ± |

2.1 ± |

2 |

L32 |

L |

Fusiform |

C3 |

6.4 |

- |

3 |

5.0 ± |

3.0 ± |

2.2 ± |

2 |

L39 |

L |

Fusiform |

C3 |

7.1 |

- |

3 |

5.0 ± |

2.7 ± |

2.2 ± |

2 |

L8 |

L |

Fusiform |

C3 |

7.5 |

- |

3 |

5.0 ± |

1.2 ± |

1.5 ± |

2 |

L14 |

L |

Fusiform |

C3 |

7.4 |

- |

3 |

5.0 ± |

1.5 ± |

1.3 ± |

2 |

L25 |

L |

Fusiform |

C3 |

7.3 |

- |

3 |

4.2 ± |

1.7 ± |

2.3 ± |

2 |

L43 |

L |

Fusiform |

C3 |

6.8 |

- |

3 |

4.1 ± |

2.6 ± |

1.9 ± |

2 |

L29 |

L |

Fusiform |

C3 |

6.7 |

- |

3 |

4.7 ± |

2.0 ± |

1.9 ± |

2 |

F15 |

F |

Fusiform |

C3 |

6.8 |

- |

3 |

5.0 ± |

2.6 ± |

1.7 ± |

2 |

F16 |

F |

Fusiform |

C3 |

7.2 |

- |

3 |

5.0 ± |

2.7 ± |

1.6 ± |

2 |

F19 |

F |

Fusiform |

C3 |

7.3 |

- |

3 |

5.0 ± |

2.0 ± |

1.5 ± |

2 |

F23 |

F |

Fusiform |

C3 |

6.2 |

- |

3 |

5.0 ± |

2.3 ± |

1.5 ± |

2 |

F45 |

F |

Fusiform |

C3 |

6.3 |

- |

3 |

5.0 ± |

2.8 ± |

1.0 ± |

2 |

F32 |

F |

Fusiform |

C3 |

6.7 |

- |

3 |

4.6 ± |

2.7 ± |

1.2 ± |

2 |

F12 |

F |

Fusiform |

C3 |

7.5 |

- |

3 |

4.2 ± |

3.0 ± |

1.4 ± |

2 |

F17 |

F |

Fusiform |

C3 |

7.8 |

- |

3 |

4.7 ± |

2.1 ± |

1.0 ± |

2 |

F2 |

F |

Fusiform |

C3 |

7.9 |

- |

3 |

5.0 ± |

1.6 ± |

1.3 ± |

2 |

F46 |

F |

Fusiform |

C3 |

6.5 |

- |

3 |

5.0 ± |

1.7 ± |

1.8 ± |

2 |

F26 |

F |

Fusiform |

C3 |

6.3 |

- |

3 |

5.0 ± |

1.8 ± |

1.7 ± |

2 |

M12 |

M |

Fusiform |

C3 |

6.4 |

- |

3 |

4.8 ± |

1.9 ± |

1.6 ± |

2 |

M46 |

M |

Fusiform |

C3 |

6.2 |

- |

3 |

5.0 ± |

1.5 ± |

1.8 ± |

2 |

M47 |

M |

Fusiform |

C3 |

6.7 |

- |

3 |

4.7 ± |

1.2 ± |

1.9 ± |

2 |

M43 |

M |

Fusiform |

C3 |

7.2 |

- |

3 |

4.6 ± |

1.7 ± |

1.5 ± |

2 |

M33 |

M |

Fusiform |

C3 |

7.4 |

- |

3 |

4.9 ± |

1.4 ± |

1.2 ± |

2 |

M2 |

M |

Fusiform |

C3 |

7.4 |

- |

3 |

5.0 ± |

1.3 ± |

1.1 ± |

2 |

M11* |

M |

Fusiform |

C3 |

6.7 |

- |

3 |

5.0 ± |

3.2 ± |

1.0 ± |

2 |

Notes: References: a: name of the main strawberry production areas in Tucumán where the isolates were collected; L: Lules; F: Famaillá; M: Manantial. b: Three different conidia shapes were described; Cylindrical-1 (cylindrical conidia with straight sides and rounded on both ends), Cylindrical-2 (cylindrical conidia with one pointed end and the other rounded), Fusiform (with both ends tapered to a point). c: Colony colours of 12-day-old cultures on PDA; C1 (olive to dark grey with white centre and the underside of the colony dark-olive to dark grey), C2 (white to pale beige and underside of the colony grey to dark-olive near the centre, white at the edges of the colony), C3 (orange with a pink-orange underside). d: Colony diameters of 12-day-old cultures on PDA; e: Presence (+) or absence (-) of perithecia; f: Groups are classified according to isolates’ microbiological analyses; g: Groups classifies according to isolates’ phytopathological analyses. *Authenticated isolates by Commonwealth Mycological Institute (CABI); F7 (IMI 386394), isolate L9 of C. acutatum (L9: 386396), M11 (386395).

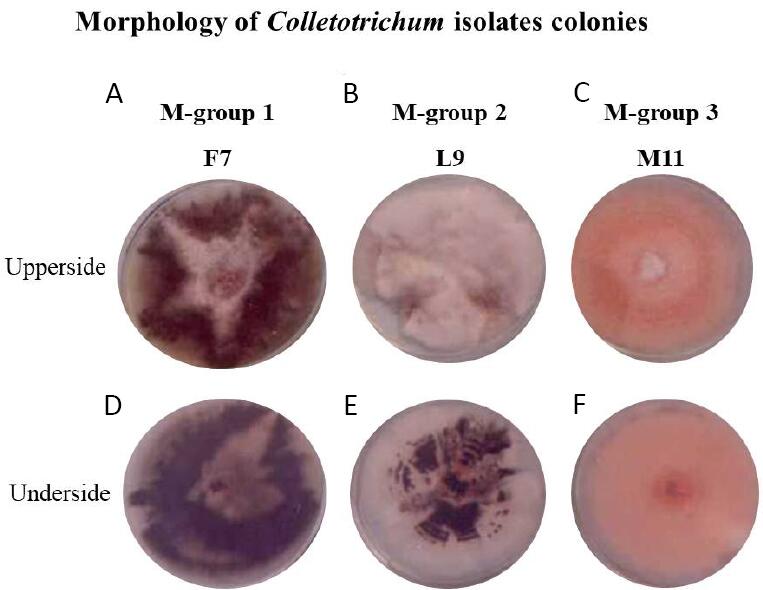

Thereafter, based on morphological characteristics, the 45 isolates were divided into three distinctive groups, mainly according to conidial shape and colony colour, namely M-group 1 (the M denotes “morphological classification”, which included 10 isolates), M-group 2 (4 isolates), and M-group 3 (31 isolates) (Table 1). Colonies of the M-group 1 isolates were olive to dark grey with a white centre, presenting abundant aerial mycelium (Figure 1A), and the underside was dark-olive to dark grey, with an average diameter of 8.3cm (Figure 1B). Colonies of M-group 2 isolates presented white to pale beige colonies with abundant aerial mycelium (Figure 1C), and the underside was grey to dark-olive near the centre and white at the edges, with an average diameter of 4.6cm (Figure 1D). Whereas colonies of M-group 3 isolates showed white colonies during the first two days of growth, but later turned orange with scarce aerial mycelium, abundant asexual fructification bodies (e.g., acervuli) (Figure 1E), and the underside colonies were pink-orange, with an average diameter of 7.1cm (Figure 1F).

|

Figure 1. Morphology of Colletotrichum isolates colonies. Upper and underside view of Colletotrichum isolates F7, L9 and M11, representing the microbiological groups 1, 2 and 3, respectively. (A, D) F7 isolate, (B, E) L9 isolate and (C, F) M11 isolate.

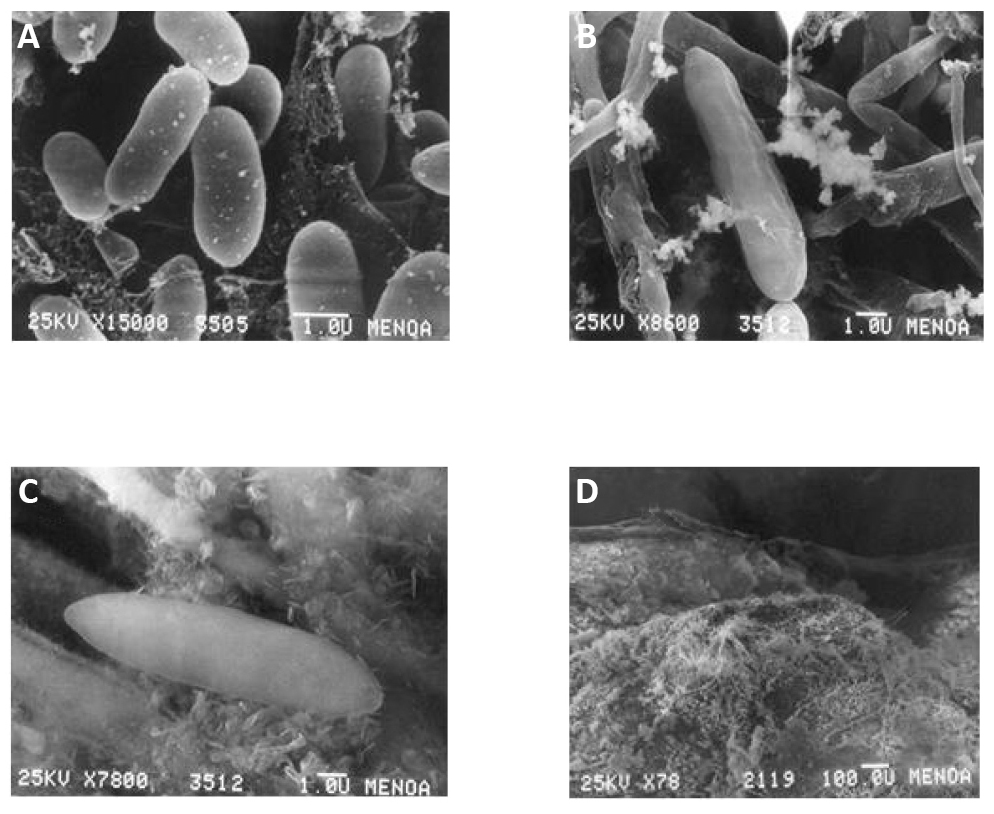

Regarding conidia, morphologies and sizes were observed among the isolates from the three morphological groups. Those from M-group 1 were cylindrical bodies with both ends rounded, with sizes ranging between 11.0-8.9mm long and 4.1-3.2mm wide (Figure 2A; named as Cylindrical-1 in Table 1). Conidia from M-group 2 were predominantly cylindrical with one pointed end and the other rounded with sizes ranging between 14.5-12.7mm long × 4.5-3.9mm wide (Figure 2B; named as Cylindrical-2 in Table 1). Conidia from M-group 3 were fusiform, with both ends tapered to a point and sizes ranging between 21.3-18.7mm long × 6.1-4.8mm wide (Figure 2C; named Cylindrical-3 in Table 1).

|

Figure 2. Microscopic observations of Colletotrichum conidia. A: Isolate F7, cylindrical conidia with both rounded ends; B: Isolate L9, predominantly cylindrical conidia with a pointed end and the other rounded one; C: Isolate M11, fusiform conidia with both ends tapered; D: Sexual fruiting structures (perithecia) of isolate L9 (M-group 2).

3.2 Phytopathological Characterization: Strawberry - Colletotrichum Interaction

The phytopathological assays were carried out between the 45 isolates of Colletotrichum and the cultivars 'Pájaro', 'Chandler', and 'Sweet Charlie' of F. ananassa strawberry plants. Based on their phytopathological behaviour, we clustered the fungal isolates into two different groups, namely pathogenic group 1 (P-group 1) and pathogenic group 2 (P-group 2). P-group 1 showed low virulence towards plants of cv. 'Pájaro' (DSR average=1.33±0.34), and moderate towards cv. 'Sweet Charlie' (DSR average=1.88±0.27). In general, these plants developed some visible lesions in leaflets and petioles in the first 10 days, and none or very few small lesions on petioles after 50dpi, suggesting the plant-pathogen interactions were incompatible. On the contrary, such fungal isolates showed high virulence against plants of cv. 'Chandler' (DSR average=4.32±0.60), which showed distinct lesions in petioles in the first 10dpi (Figure 3A). Whereas leaflets started to display brown circular spots surrounded by a chlorotic zone when symptoms in petioles continued to advance until developing the typical lesions of anthracnose by 15dpi (Figure 3B). The disease symptoms advanced throughout the leaves, and by 20dpi, lesions became darker and leaves completely necrotized (Figure 3C), by which time the plants were dead (Figure 3D).

|

Figure 3. Phytopathological compatible interaction between an isolate of Colletotrichum and the strawberry cv. Chandler. The fungal isolate pertained to P-group 1 and rapidly infected the plant, causing its death 20 days post-infection (dpi). A: Initial symptoms of anthracnose in petioles pointed with the arrow, 10dpi; B: Advancing symptoms in petioles (pointed with the largest arrow), and initial foliar symptoms (pointed with shorter arrows), like brown circular spots, 15dpi; C: Complete leaves necrotized by 20dpi pointed with the arrows; D: Dead plants by 20dpi.

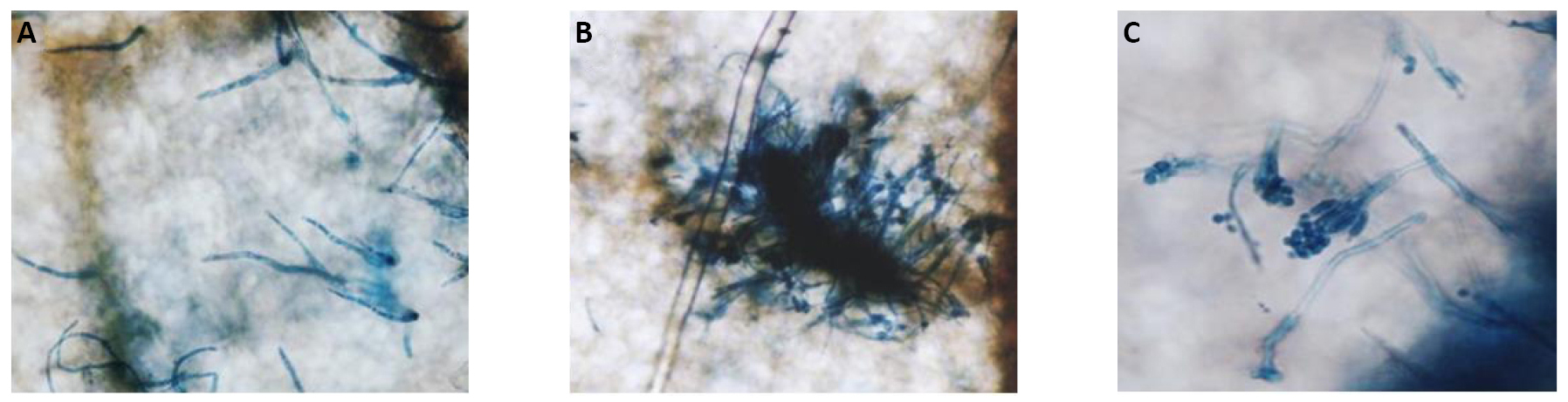

The opposite phytopathological behaviour was observed for the isolates of P-group 2. They were highly virulent towards plants of cv. 'Pájaro' (DSR average=4.81±0.29), and the plant-pathogen interaction was such a compatible one that the symptoms of the disease advanced quickly, with leaves completely necrotized and petioles strangulated by 10dpi. Signs of the pathogen were detected in the dead plant by that time (Figure 4). Whereas such fungal isolates behaved as low to moderate virulent towards plants of cv. 'Chandler' (DSR average = 2.03±0.58), and cv. 'Sweet Charlie' (DSR average = 1.59±0.40), which presented smaller and fewer lesions on petioles only by 50dpi. Plant-pathogen interactions between isolates from the P-group 2 (clustering isolates from M-group 2 and 3) and cv. 'Pájaro' and 'Chandler' were similar, without any statistically significant difference between them. However, we found that they behaved differently from the isolates from P-group 1 (clustering the isolates from M-group 1), and such different pathogenicity was statistically significant. Moreover, unlike the microbiological groups, cv. 'Sweet Charlie' behaved as a tolerant genotype towards all the isolates which renders it useless to screen phytopathological populations (Table 2).

|

Figure 4. Microscopic observations of the reproductive structures of C. acutatum M11 infecting the strawberry cv. 'Pájaro'. The fungal growth is observed on a lactophenol trypan blue-stained strawberry leaflet 10 days post infection under an optic microscope with bright-field settings. A: Setae morphology; B: The stroma; C: A conidiophore.

Table 2. Phytopathological Groups (P-group) were Observed in the Interaction among Colletotrichum Isolates with Strawberry Cultivars

|

cv. Pájaro |

cv. Chandler |

cv. Sweet Charly |

P-group |

Mean DSR |

Mean DSR |

Mean DSR |

1 |

1.33±0.34 (a) |

4.32±0.60 (b) |

1.88±0.27 (c) |

2 |

4.81±0.29 (b) |

2.03±0.58 (c) |

1.59±0.40 (c) |

3.3 Molecular Characterization of Colletotrichum Isolates

The isolates F7, L9, and M11 were selected as representatives of each microbiological group for the molecular characterization at the International Mycology Institute (CABI, England). Among the 45 isolates, only these three presented clear and stable microbiological features and showed reliable and stable phytopathological behaviours. Most of other isolates met one or the other criterion, but it was important to ensure both criteria were met. For example, some strains showed high and stable virulence but produced little amount of conidia, and others yielded a larger number of conidia.

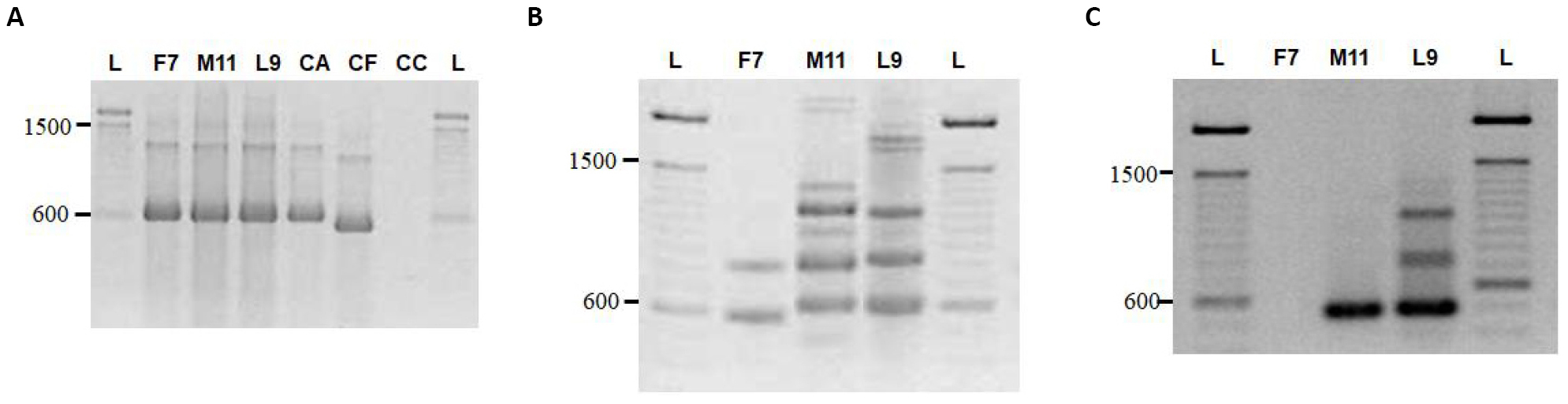

By amplifying regions of mitochondrial small rRNA gene by PCR analysis, we confirmed that the isolates F7, L9, and M11 (IMI 386394, 386396 and 386395, respectively) corresponded to C. acutatum species since the same band of approximately 600bp was observed for two of the Colletotrichum species used as reference control namely, C. acutatum and C. fragariae (Figure 5A). Whereas such a band was not detected for the third reference species used (Colletrotrichum. coccodes), and a possible explanation is that despite NMS1 and NMS2 primers being designed to amplify a mitochondrial small rRNA region for fungi belonging to the class Ascomycetes, the detection or the intensity of the bands is dependent on the different species, as observed by Howard et al.[34].

Moreover, genomic polymorphisms were observed among the isolates F7, L9 and M11 when using the minisatellite arbitrary primers (GAGA)4 and (CGT)5 (Figure 5B) and the specific primers CaInt2/ITS4 (Figure 5C). Similarly, the band corresponding to the amplification product of the specific primers CaInt2/ITS4 (Figure 5C) was not detected in the F7 isolate.

|

Figure 5. Molecular characterization of the Colletotrichum isolates F7, M11 and L9. A: The identity of the isolates was confirmed by PCR analysis since the molecular profiles were identical to that of the reference species of C. acutatum (CA). B and C: Genomic polymorphisms were observed among the isolates F7, L9 and M11 when using the minisatellite arbitrary primers (GAGA)4 and (CGT)5 (B) and the specific primers CaInt2/ITS4 (C). References: L: Ladder (100pb molecular marker, 15628019, Invitrogen, USA); CA: C. acutatum reference species; CF: C. fragariae reference species; CC: C. coccodes reference species.

3.4 Phytopathogenicity Confirmation of C. acutatum Isolates

To confirm the phytopathological behaviour of the isolates F7 and M11 of C. acutatum, we further challenged them towards commercial strawberry cultivars amply used in the productive area of Tucumán. We observed that the plant-pathogen interactions were strongly dependent on cultivar and fungal strain. Whilst cv. 'Pájaro' and 'Oso Grande' were more susceptible to M11, and 'Chandler' and 'Rosalinda' were more susceptible to F7. Moreover, 'Gaviota', 'Camarosa', 'Selva' and 'Sweet Charlie' showed tolerance towards both isolates, whereas 'Enzed Donna' and 'Rosalinda' were susceptible and moderately tolerant to both isolates. The most contrasting plant-pathogen interactions occurred between cv. 'Pájaro' and 'Chandler' and such fungal isolates, whereas cv. 'Chandler' displayed the highest susceptibility towards F7, and relative tolerance to M11, cv. 'Pájaro' showed the opposite behaviour. The isolate M11 severely infected cv. 'Pájaro', developing a strong compatible interaction, while F7 failed to infect it, showing a clear incompatible interaction.

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 A Polyphasic Approach to Characterize Colletotrichum Species Present in the Strawberry Production Area of Tucumán

Colletotrichum spp. has traditionally been classified based on the shape of the conidia and appressorium, the presence of perithecium, and culture characteristics[3,40]. The conidia sizes observed among these local isolates of Colletotrichum differ from those reported in the literature[32,40]. Isolates of M-group 1 produced smaller conidia, and isolates of M-group 3 produced larger conidia than previously reported ones. The only strains that produced perithecia with asci and ascospores typical of G. cingulata[2,51,54], were those included in the M-group 2 (Figure 2D), except isolate L11 (Table 1). All the other isolates failed to produce perithecia under the experimental conditions assayed in the present study. Following this classical methodology based on the analysis of cultural and morphological features, the isolates from M-group 1 should be featured as C. fragariae, those from M-group 2 as C. gloesporioides, and those from M-group 3 as C. acutatum. However, it is well known that morphological characterization is insufficiently reliable to classify Colletotrichum isolates at the species level. Indeed, only for the M11 isolate, microbiological criteria of classification led to an accurate result, matching such isolate as C. acutatum, which later was confirmed by molecular analysis.

We further performed phytopathological and molecular assays to complement this preliminary classical characterization. Such analyses precisely determined that the isolates F7 and L9 belong to the same species of C. acutatum, though they display typical phenotypical traits of C. fragariae and C. gloeosporioides, and are tentatively classified as so based on their morphological features. Such a disagreement between the information from classical and molecular analyses had been reported by Ramallo et al.[47] in strawberry. By using Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analyses, they found significant genomic differences in a group of isolates that were considered the same species according to classical techniques. Likewise, they could establish a closer genomic relationship among other isolates that were considered different species according to classical methods[47]. However, their screening based on morphological features and RAPD analysis was still inadequately reliable to determine the Colletotrichum population present in Tucumán, Argentina; the use of one molecular technique alone is of little importance to reach such a conclusion. For instance, Ramallo et al’s study, Buddie et al.[48] thoroughly discussed the advantages of different molecular techniques for the characterization of Colletotrichum species. They especially highlighted to the difficulty in classifying Colletotrichum isolates into species due to the lack of a clear definition of species in this taxonomic group. They showed that results depend on the particular technique used; therefore, information from microbiological and morphological studies are still required for a correct classification of these species into taxonomic hierarchies. Since then, such a polyphasic approach based on morphology and genetic characteristics was incorporated, and years later reaffirmed by Cai et al[41].

In the present study, the polyphasic approach was applied, resulting in the first study to report with confidence that the species present in the main-production strawberry region in Tucumán, Argentina correspond to C. acutatum. Similarly, using this polyphasic approach, other authors have successfully identified many C. acutatum isolates from strawberries[1,37,43,60-64].

4.2 Colletotrichum acutatum Species Present in Tucumán are Genetically Diverse

The existence of a large genotypical diversity within the population of C. acutatum species in strawberry fields in Tucumán, Argentina was revealed. In line with our observations, in the first study reporting the presence of Colletotrichum species in Tucumán, Ramallo et al.[47] also detected considerable genetic diversity using RAPD PCR. Interestingly, alterations in the composition of Colletotrichum species may have occurred in the strawberry-productive area of Tucumán over the years as earlier reports indicated that C. fragariae was the dominant species present in the area[47,52]. The reason for this hypothetical exchange remains elusive, but we may speculate that the substitution of strawberry cultivars farmers have carried out in the last years, from 'Chandler' and 'Sweet Charlie' to 'Camarosa', may have been the main exchange factor. Another valid possibility is that no changes may have occurred ever since and that the species initially characterized as C. gloesporoides using morphological criteria led to erroneous results. Instead, C. acutatum has always been the pathogen present in the strawberry productive area of Tucumán. Irrespective of the correct answer, what we do know is that C. acutatum is the dominant species present in the area, which is necessary to know to implement the correct disease control methods.

4.3 The Strawberry Cultivar 'Pájaro' Activates A Defensive Response Towards Pathogens

The cv. 'Pájaro' activates an “on/off” defensive response depending on which fungus is challenged. Based on antecedents, we confirmed that M11 inhibits the plant's innate mechanism of defence and rapidly propagates throughout the plant, killing it as fast as 10dpi[65]. Moreover, M11 produces a diffusible compound that suppresses the biochemical, physiological, molecular and anatomical events associated with the defence response induced by an elicitor[66]. Unlike M11, isolate F7 induces a mechanism of defence in cv. 'Pájaro', which may explain the incompatibility of the interaction. In this vein, we have demonstrated in a previous study that strawberry plants previously challenged to an avirulent isolate of C. fragariae induced a defence response and acquired strong resistance against a virulent strain of C. acutatum[67]. Similarly, Racedo et al.[68] demonstrated that the avirulent isolate SS71 of Acremonium strictum -a strawberry occasional pathogen, induced a defence response in the cv. 'Pájaro', rendering strawberry plants resistant to the subsequent attack of the virulent isolate M11 of C. acutatum[69].

None of the other strawberry genotypes evaluated in this study presented such behaviour. Taken together, the current results demonstrate that the severity of the plant-pathogen interactions depend on the genotypes of the fungi and strawberry plants challenged since different strawberry cultivars respond differently when challenged by the same fungal isolate. This phenomenon has already been reported by Denoyes-Rothan et al.[37] and Denoyes-Rothan et al.[70], revealing that the interaction between strawberry plants and Colletotrichum has to be considered based on specific genotypes because each cultivar may differently tolerate the attack of pathogens present within the fungal complex at the moment of infection. Hence, the importance of assessing the populations of pathogens present in an agroecological system, together with a correct phytopathological evaluation of the pathogens' genotypes and strawberry cultivars used.

5 CONCLUSION

The present study reports with confidence for the first time the presence of C. acutatum species in the main-production strawberry region in Tucumán, Argentina, and the C. acutatum species is genetically diverse. Changes in the composition of Colletotrichum species have occurred in the strawberry-productive area of Tucumán over the years. This knowledge will help to accurately implement the correct disease control methods.

5.1 A Revision of Biological Control Agents Available on Markets and under Research to Control Colletotrichum in the Strawberry Crop

Biological Control Agents (BCAs) have emerged in the last few years as a healthier alternative to synthetic agrochemicals. They include microbe-derived elicitors, microbe-derived extracts, plant-derived extracts, and any compound derived from a biological source. In this review, we will focus on BCAs with activity towards Colletotrichum species for the control of anthracnose in the pre- and post-harvest strawberry crop.

BCAs offer an utmost feature that chemical fungicides cannot reach-at least until today, and that is the capacity to activate plants’ innate immune responses, which is supposed to be unable to develop fungal resistance towards such BCA. In contrast, traditional fungicides act on one particular fungal process, which may lead to the emergence of some resistant fungal strains to that chemical. Farmers count on alternative practices to overcome such resistance, such as changing the current fungicide to one with a different mode of action or a multi-site one, whereby the eventual potential for resistance is greatly reduced. Nevertheless, many chemical fungicides still negatively impact the environment and human and animal’s health[71]. For instance, many of the fungicides recommended for strawberry anthracnose crown rot and fruit rot management[72] have been described for their low, medium or high risk for resistance evolution, according to the principles described in the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (FRAC)[73].

The FRAC code list has recently incorporated two categories of fungicides of biological and natural origins, namely by their mode of action as “P: host plant defence induction”, including salicylate-related compounds (codes P01-P03, and P 08), anthraquinone elicitors (code P 05), microbial elicitors (code P 06), and phosphonates (code P 08); and “BM: Biologicals with multiple modes of action: Plant extracts”, including plant extracts (code BM 01) and microbial strains of living microbes or microbially-derived extracts and metabolites (code BM 02) (FRAC, 2022). In Table 3, we include those OMRI Listed® supplies of biological origin that are commercially available, which are ratified for use in certified organic operations under the United States Department of Agriculture national organic program. In Table 4, we include those research that tested a BCA -such as whole microbes, microbially-derived extracts or plants essential oils, both in vitro and on a greater scale like greenhouse and field trials to control anthracnose in the strawberry crop.

Table 3. Biological Products Commercially Available and OMRI® Listed to Control Anthracnose in the Strawberry Crop

Name of Product |

Microorganism / Plant Species |

Type of BCAs |

Strawberry Cultivar host |

Colletotrichum Species Target |

Mode of Action |

Crown rot Efficacy |

Fruit rot Efficacy |

Antifungal Activity |

OMRI Certified |

Formulation |

Application Method |

Doses BCAs |

Results |

Link |

Howler® |

Acremonium strictum SS71 |

Fermentation soluble proteins |

Fragaria sp. |

Colletotrichum sp. |

Plant Defence Activator |

Yes |

n.s. |

No |

n.s. |

Liquid |

Field: pre-harvest spray applications in sufficient water to cover the aerial tissues of plants with minimal run-off; 3 or 4 applications every 30 days |

2 l/ha |

Howler -complements but does not substitute fertilizers commonly applied into the soil; it also may improve control of post-harvest infections. |

|

Tusal® |

T. harzianum T11 T. asperellum T25 |

Whole fungi |

Camarosa´ |

C. acutatum |

Plant Defence Activator Biofungicide |

Yes |

n.s. |

Yes |

Yes |

Suspension of conidia |

Field: Drip irrigation; addition to the soil 7-days before planting Field: Roots dipping before planting |

108 cd/m2

106 cd/mL |

58.6% reduction of anthracnose incidence and 63.5% in plant mortality, relative to control. |

|

Natamycin L |

Streptomyses natalensis |

Fermentation crystals |

´Monterey´ ´Portola´ ´Fronteras´ |

C. acutatum and C. acutatum QoI-resistant |

Biofungicide |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Liquid suspension |

Field: Pre-plant dip: immerse bare-root, cut-off plants or tips for 2-5min. |

500 - 1000 mg/l |

Disease severity and plant mortality were reduced to similarly low levels as the conventional fungicide fludioxonil; fruit yield significantly increased relative to control. |

|

Botector® |

Aureobasidium pullulans |

Whole yeast |

Fragaria sp. |

C. acutatum |

Biofungicide |

n.s. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Water dispersible granule |

Field: Apply preventatively or at the first sign of disease; 6 applications per year (repeat as needed on a 7-10 days interval) up to harvest |

1kg/ha

(500-1,000l/ha water volume) |

Suppression of fruit rot appearance; reduces the number of resistant pathogens in the population. |

|

Serenade ASO |

Bacillus subtilis QST 713 |

Whole microbe |

Fragaria sp. |

C. gloeosporioides C. acutatum |

Plant Defence Activator |

Yes |

Yes |

n.s. |

Yes |

Suspension of conidia |

Field: Foliar application. Can be tank-mixed with other in-furrow products like fungicides or fertilizers and applied using existing spray or chemigation equipment |

5,6 - 11,2 l/ha 2.8-11,2l/ha (tank mixed) |

Activates natural plant defences by priming systemic responses, promoting growth and stress resistance. |

Notes: The supplies are OMRI Listed®. This list is not considered to be complete; any omissions or errors are regretted. Furthermore, indications of these products by the authors do not in any way signify an endorsement of the product or manufacturer/distributor. References: BCAs: biological control agents; n.s.: not specified; cd: conidia. Metric conversions: to convert litre/hectare to a gallon/acre divide in 11.21; to convert kg/ha to lb./acre divide in 1.12.

Table 4. In vitro and In-field Application of Different BCAs under Research to Control Anthracnose in Strawberry

Microorganism / Plant species |

Type of BCA |

Strawberry Cultivar host |

Colletotrichum Species Target |

Formulation |

Mode of Action |

Crown rot Efficacy |

Fruit rot Efficacy |

Antifungal Activity |

Application Method |

Dosis BCA |

Results |

Link |

Whole bacterium |

Bacillus velezensis NSB-1 |

´Seolhyang´ |

C. gloeosporioides |

Suspension of conidia |

Biofungicide |

Yes |

n.t. |

Yes |

In vitro: Spray until run-off; applications pre- and post-inoculation of the pathogen. |

105, 106, 107CFU/mL |

76.5% protective efficacy and 65% of curative control efficacy relative to control; n.s. d. with the conventional fungicide Prochloraz-Mn. |

|

Field: Spray until run-off with 7, 10 or 14 days intervals |

107CFU/mL |

73,2% and 70,6% protection respect to non-treated plants, when applied every 7 or 10 days respectively. |

||||||||||

Plant Essential Oils (EOs) |

Achillea millefolium Mentha longifolia Ferula kuma |

´Paros´ |

C. nymphaeae |

Suspension and Vapour phase |

Biofungicide |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

In vitro: Drop of EOs solution or EOs vapours on PDA plates, before pathogen infection. |

600-2100µL/L for each EOs |

All EOs sign. reduced mycelial growth and conidial germination both in contact and vapour phases, relative to non-treated control, similar to Captan. |

|

Post-harvest: Fruits treated with EOs solution + pathogen inoculation at the same time. |

600-2100µL/L for each EOs |

All EOs sign. decreased fruits' postharvest decay relative to non-treated control, and similar to Captan. |

||||||||||

Whole fungus and bacterium |

B. amyloliquefaciens Bc2 T. harzianum T11 |

´Sabrina´ |

C. acutatum |

Suspension of conidia |

n.s. |

Yes |

n.t. |

Yes |

In vitro: Leaflets simultaneously inoculated with suspensions of either BCA + pathogen. |

105spores/mL (T11)

3×105CFU/mL (Bc2) |

In vitro: 'Both BCA controlled 100% the appearance of anthracnose, with 0% incidence on the leaflets. |

|

´Fortuna´ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Field: 6g BCA-pre-inoculated substrate mixed with the soil of a ridge with 500 plants. |

105spores/g mL (T11); 3×105CFU/g (Bc2) |

Field: Both BCA controlled anthracnose, grey mould and powdery mildew; they also promoted increments of plant size and fruit number. |

|

||

Bacterium-derived extract |

Bacillus safensis QN1NO-4 (novel sp.) |

´Zhang Ji´ |

C. fragariae |

PDA-diluted extract |

Biofungicide |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

In vitro: PDA plate prepared with different concentrations of the extract + pathogen. |

1.56, 3.12, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200mg/L |

All the concentrations inhibited pathogen growth, with the EC50 value of the extract defined as 33.81±0.46mg/l. |

|

In vitro: Tube prepared with an equal vol of pathogen spore suspension + extract. |

4×EC50 |

Spore germination was increasingly inhibited with higher extract doses (100% inhibition with 4×EC50); changes in hyphae morphology and conidia ultrastructure. |

||||||||||

Post-harvest: Fruit wounded and inoculated with 10µL BCA + 10µL pathogen. |

1×EC50, 2 ×EC50, 4× EC50, 8× EC50 |

The extract reduced the incidence of anthracnose in harvested fruits; fruits' weight and TSS contents were maintained sign. |

Notes: This list was performed based on the criteria that researchers have tested the effect of BCAs at least in vitro at the laboratory level and on a greater scale such as greenhouse or field. It is not considered complete, and any omissions or errors are regretted. Furthermore, indications of these studies by the authors do not signify an endorsement of the researchers or institutions. References: BCAs, biological control agents; n.s., not specified; n.t., not tested; n.s.d., no statistical differences; hpi, hours previous inoculation; sign., significantly; TTS, total soluble solids; EC50, half-maximal effective concentration of the extract against the pathogen.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The manuscript has not been published and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere. All authors have approved the manuscript and agreed to submit the paper to the Journal of Modern Agriculture and Biotechnology. The research was conducted in the absence of any commercial relationships that could be considered a potential conflict of interest.

Author Contribution

Sergio MS performed the experiments and analyzed and interpreted the data. Ramiro NF collaborated in DSR determinations. Marta EA and Sergio MS made the epidermis preparations, and leaf and root cuts, and analyzed and interpreted the anatomical data. Sebastián NM analyzed and interpreted the data. Sergio MS wrote the manuscript, and Atilio PC and Juan CDR critically reviewed the article. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Abbreviation List

BCAs, Biological control agents

C. acutatum, Colletotrichum acutatum

C. fragariae, Colletotrichum fragariae

C. gloeosporioides, Colletotrichum gloeosporioides

CABI, Commonwealth Mycological Institute

cv., Cultivar

Dpi, Days post-infection

DSR, Disease severity rating

F7, Isolate F7 of Colletotrichum acutatum

FRAC, Fungicide Resistance Action Committee

G. cingulate, Glomerella cingulata

ITS, Internal transcribed spacer

L9, Isolate L9 of Colletotrichum acutatum

M11, Isolate M11 of Colletotrichum acutatum

PCR, Polymerase chain reaction

PDA, Potato dextrose agar

RAPD, Random amplified polymorphic DNA

rDNA, ribosomal

References

[1] Damm U, Cannon PF, Woudenberg JHC et al. The Colletotrichum acutatum species complex. Stud Mycol, 2012; 73: 37-113. DOI: 10.3114/sim0010

[2] Sutton BC. The genus Glomerella and its anamorph Colletotrichum. CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1992.

[3] Cannon PF, Damm U, Johnston PR et al. Colletotrichum-Current status and future directions. Stud Mycol, 2012; 73: 181-213. DOI: 10.3114/sim0014

[4] Baroncelli R, Talhinhas P, Pensec F et al. The Colletotrichum acutatum species complex as a model system to study evolution and host specialization in plant pathogens. Front Microbiol, 2017; 2001: 8. DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02001

[5] Garrido C, Carbú M, Fernández-Acero F et al. Phylogenetic relationships and genome organisation of Colletotrichum acutatum causing anthracnose in strawberry. Eur J Plant Pathol, 2009; 125: 397-411. DOI: 10.1007/s10658-009-9489-0

[6] Debode J, Van Hemelrijck W, Xu XM et al. Latent entry and spread of Colletotrichum acutatum (species complex) in strawberry fields. Plant Pathol, 2015; 64: 385-395. DOI: 10.1111/ppa.12247

[7] CABI. Colletotrichum acutatum (black spot of strawberry). Accessed March 12, 2022. Available at https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/10.1079/cabicompendium.14889

[8] Lee DH, Kim DH, Jeon YA et al. Molecular and cultural characterization of Colletotrichum spp. Causing bitter rot of apples in Korea. Plant Pathol J, 2007; 23: 37-44. DOI: 10.5423/PPJ.2007.23.2.037

[9] Moreira RR, Peres NA, May De Mio LL. Colletotrichum acutatum and C. gloeosporioides species complexes associated with apple in Brazil. Plant Dis, 2018; 103. DOI: 10.1094/PDIS-07-18-1187-RE

[10] Khodadadi F, González J, Martin P et al. Identification and characterization of Colletotrichum species causing apple bitter rot in New York and description of C. noveboracense sp. Nov. Sci Rep-Uk, 2020; 10: 1-19. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-66761-9

[11] Aćimović S, Martin P, Khodadadi F et al. One disease many causes: The key Colletotrichum species causing apple bitter rot in New York, Pennsylvania and Virginia, their distribution, habitats and management options. Accessed March 12, 2022. Available at https://cpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/blogs.cornell.edu/dist/7/7077/files/2021/01/03_Acimovicarticle_FINAL.pdf

[12] Peres NA, MacKenzie SJ, Peever TL et al. Postbloom fruit drop of citrus and key lime anthracnose are caused by distinct phylogenetic lineages of Colletotrichum acutatum. Phytopathology, 2008; 98: 345-352. DOI: 10.1094/PHYTO-98-3-0345

[13] Wang W, de Silva DD, Moslemi A et al. Colletotrichum species causing anthracnose of citrus in Australia. J Fungi, 2021; 7: 47. DOI: 10.3390/jof7010047

[14] Riolo M, Aloi F, Pane A et al. Twig and shoot dieback of citrus, a new disease caused by Colletotrichum species. Cells, 2021; 10: 449. DOI: 10.3390/cells10020449

[15] Khanchouch K, Pane A, Chriki A et al. Major and emerging fungal diseases of citrus in the mediterranean region. Citrus Pathology, 2017; 1: 66943. DOI: 10.5772/66943

[16] Rhaiem A, Taylor PWJ. Colletotrichum gloeosporioides associated with anthracnose symptoms on citrus, a new report for Tunisia. Eur J Plant Pathol, 2016; 146: 219-224. DOI: 10.1007/s10658-016-0907-9

[17] Talhinhas P, Mota-Capito C, Martins S et al. Epidemiology, histopathology and etiology of olive anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum acutatum and C. gloeosporioides in Portugal. Plant Pathol, 2011; 60: 483-495. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2010.02397.x

[18] Moral J, Agustí-Brisach C, Raya MC et al. Diversity of Colletotrichum species associated with olive anthracnose worldwide. J Fungi, 2021; 7: 741. DOI: 10.3390/jof7090741

[19] Gomes S, Prieto P, Martins-Lopes P et al. Development of Colletotrichum acutatum on tolerant and susceptible olea europaea L. cultivars: A microscopic analysis. Mycopathologia, 2009; 168: 203-211. DOI: 10.1007/s11046-009-9211-y

[20] Talhinhas P, Loureiro A, Oliveira H. Olive anthracnose: A yield- and oil quality-degrading disease caused by several species of Colletotrichum that differ in virulence, host preference and geographical distribution. Mol Plant Pathol, 2018; 19: 1797-1807. DOI: 10.1111/mpp.12676

[21] Moral J, Xaviér CJ, Viruega JR et al. Variability in susceptibility to anthracnose in the world collection of olive cultivars of cordoba (Spain). Frontiers in Plant Science, 2017; 8: 1892. DOI: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01892

[22] Polashock JJ, Oudemans PV, Caruso FL et al. Population structure of the North American cranberry fruit rot complex. Plant Pathol, 2009; 58: 1116-1127.

[23] Sabaratnam S, Wood B, Nabetani K et al. Surveillance of cranberry fruit rot pathogens, their impact and grower education. Accessed November 14, 2014. Available at https://www.bccranberries.com/pdfs/researchreports/2014/4d2014_Sabaratnam_Interim_Research_Report.pdf

[24] Wharton PS, Schilder AC. Novel infection strategies of Colletotrichum acutatum on ripe blueberry fruit. Plant Pathol, 2008; 57: 122-134. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2007.01698.x

[25] Soares VF, Velho AC, Stadnik MJ. First report of Colletotrichum chrysophilum causing anthracnose on blueberry in Brazil. Plant Dis, 2022; 106: 322. DOI: 10.1094/PDIS-04-21-0873-PDN

[26] Xu CN, Zhou ZS, Wu YX et al. First report of stem and leaf anthracnose on blueberry caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides in China. Plant Dis, 2013; 97: 845-845. DOI: 10.1094/PDIS-11-12-1056-PDN

[27] Liu X, Zheng X, Khaskheli M et al. Identification of Colletotrichum Species associated with blueberry anthracnose in Sichuan, China. Pathogens, 2020; 9: 718. DOI: 10.3390/pathogens9090718

[28] Lee DM, Hassan O, Chang T. Identification, characterization, and pathogenicity of Colletotrichum species causing anthracnose of peach in Korea. Mycobiology, 2020; 48: 210-218. DOI: 10.1080/12298093.2020.1763116

[29] College of Agriculture, Food and Environment. Strawberry anthracnose fruit & crown rot. Accessed March 12, 2022. Available at https://plantpathology.ca.uky.edu/files/ppfs-fr-s-05.pdf

[30] Brooks AN. Anthracnose of strawberry caused by Colletotrichum fragariae. Phytopathology, 1931; 21: 739-744.

[31] Delp BR, Milholland RD. Evaluating strawberry plants for resistance to Colletotrichum fragariae. Plant Dis, 1980; 64: 1071-1073. DOI: 10.1094/PD-64-1071

[32] Smith BJ, Black LL. Morphological, cultural, and pathogenic variation among Colletotrichum species isolated from strawberry. Plant Dis, 1990; 74: 69-76. DOI: 10.1094/PD-74-0069

[33] Freeman S, Katan T. Identification of Colletotrichum species responsible for anthracnose and root necrosis of strawberry in Israel. Phytopathology, 1997; 87: 516-521. DOI: 10.1094/PHYTO.1997.87.5.516

[34] Howard CM, Maas JL, Chandler CK et al. Anthracnose of strawberry caused by the Colletotrichum complex in Florida. Plant Dis, 1992; 76: 976-981. DOI: 10.1094/PD-76-0976

[35] Mertely JC, Legard DE. Detection, isolation, and pathogenicity of Colletotrichum spp. from strawberry petioles. Plant Dis, 2004; 88: 407-412. DOI: 10.1094/PDIS.2004.88.4.407

[36] Adaskaveg JE, Hartin RJ. Characterization of Colletotrichum acutatum isolates causing anthracnose of almond and peach in California. Phytopathology, 1997; 87: 979-987. DOI: 10.1094/PHYTO.1997.87.9.979

[37] Denoyes-Rothan B, Guérin G, Délye C et al. Genetic diversity and pathogenic variability among isolates of Colletotrichum species from strawberry. Phytopathology, 2003; 93: 219-228. DOI: 10.1094/PHYTO.2003.93.2.219

[38] Freeman S, Katan T, Shabi E. Characterization of Colletotrichum species responsible for anthracnose diseases of various fruits. Plant Dis, 1998; 82: 596-605. DOI: 10.1094/PDIS.1998.82.6.596

[39] Liu F, Cai L, Crous PW et al. The Colletotrichum gigasporum species complex. Persoonia-Molecular Phylo Evol Fungi, 2014; 33: 83-97. DOI: 10.3767/003158514X684447

[40] Gunnell PS, Gubler WD. Taxonomy and morphology of Colletotrichum species pathogenic to strawberry. Mycologia, 1992; 84: 157-165. DOI: 10.1080/00275514.1992.12026122

[41] Cai L, Hyde KD, Taylor PW et al. A polyphasic approach for studying Colletotrichum. Fungal Divers, 2009; 39: 183-204.

[42] Hyde KD, Cai L, McKenzie EHC et al. Colletotrichum: A catalogue of confusion. Fungal Divers, 2009; 39: 1-17.

[43] Vieira WAS, Lima WG, Nascimento ES et al. The impact of phenotypic and molecular data on the inference of Colletotrichum diversity associated with Musa. Mycologia, 2017; 109: 912-934. DOI: 10.1080/00275514.2017.1418577

[44] Sreenivasaprasad S, Sharada K, Brown AE et al. PCR-based detection of Colletotrichum acutatum on strawberry. Plant Pathol, 1996; 45: 650-655. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-3059.1996.d01-3.x

[45] Sreenivasaprasad S, Meehan BM, Mills PR et al. Phylogeny and systematics of 18 Colletotrichum species based on ribosomal DNA spacer sequences. Genome, 1996; 39: 499-512. DOI: 10.1139/g96-064

[46] Freeman S, Rodriguez RJ. Differentiation of Colletotrichum species responsible for anthracnose of strawberry by arbitrarily primed PCR. Mycol Res, 1995; 99: 501-504. DOI: 10.1016/S0953-7562(09)80653-9

[47] Ramallo CJ, Ploper D, Ontivero MP et al. Estudios morfológicos, culturales y genéticos de especies de Colletotricum que afectan frutilla en Argentina. Brazilian Phytopathology, 1997; 22: 300.

[48] Buddie AG, Martínez-Culebras P, Bridge PD et al. Molecular characterization of Colletotrichum strains derived from strawberry. Mycol Res, 1999; 103: 385-394. DOI: 10.1017/S0953756298007254

[49] Kirschbaum DS, Vicente CE, Cano-Torres MA et al. Strawberry in South America: from the Caribbean to Patagonia. Acta Horticulturae, 2017; 1156: 947-956. DOI: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2017.1156.140

[50] Ramallo CJ, Ploper LD, Ontivero M et al. First report of Colletotrichum acutatum on Strawberry in Northwestern Argentina. Plant Dis, 2000; 84: 706. DOI: 10.1094/PDIS.2000.84.6.706B

[51] Mónaco ME, Salazar SM, Aprea A et al. First report of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides on Strawberry in Northwestern Argentina. Plant Dis, 2000; 84: 595. DOI: 10.1094/PDIS.2000.84.5.595C

[52] Mena AJ, De Garcia EP, González MA et al. Presencia de la antracnosis de la frutilla en la República Argentina. RANAR, 1974; 11: 307-312.

[53] Davis WH. Single Spore Isolation. P Iowa Aca Sci, 1930; 37: 151-159.

[54] Guerber JC, Correll JC. The first report of the teleomorph of Colletotrichum acutatum in the United States. Plant Dis, 1997; 81: 1334-1334. DOI: 10.1094/PDIS.1997.81.11.1334A

[55] Li KN, Rouse DI, German TL. PCR primers that allow intergeneric differentiation of ascomycetes and their application to Verticillium spp. Appl Environ Microbiol, 1994; 60: 4324-4331. DOI: 10.1128/aem.60.12.4324-4331.1994

[56] White TJ. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. Academic Press Inc.: California, USA, 1990.

[57] Di Rienzo JA, Casanoves F, Balzarini MG et al. InfoStat versión 2013. Grupo InfoStat, FCA, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina. Accessed March 12, 2022. Available at http://www.infostat.com.ar

[58] Dudley JW, Moll RH. Interpretation and use of estimates of heritability and genetic variances in plant breeding. Crop Sci, 1969; 9: 257-262. DOI: 10.2135/cropsci1969.0011183X000900030001x

[59] Freeman GH. Statistical methods for the analysis of genotype-environment interactions. Heredity, 1973; 31: 339-354. DOI: 10.1038/hdy.1973.90

[60] Xie L,Zhang J, Wan Y et al. Identification of Colletotrichum spp. isolated from strawberry in Zhejiang Province and Shanghai City, China. J Zhejiang Univ-Sc, 2010; 11: 61-70. DOI: 10.1631/jzus.B0900174

[61] Chung PC, Wu HY, Wang YW. Diversity and pathogenicity of Colletotrichum species causing strawberry anthracnose in Taiwan and description of a new species, Colletotrichum miaoliense sp. Sci Rep-Uk; 2020; 10: 1-16. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-70878-2

[62] Chung PC, Wu HY, Ariyawansa HA et al. First report of anthracnose crown rot of strawberry caused by Colletotrichum siamense in Taiwan. Plant Dis, 2019; 103: 1775. DOI: 10.1094/PDIS-12-18-2167-PDN

[63] Van Hemelrijck W, Debode J, Heungens K et al. Phenotypic and genetic characterization of Colletotrichum isolates from Belgian strawberry fields. Plant Pathol, 2010; 59: 853-861. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2010.02324.x

[64] Chen XY, Dai DJ, Zhao SF et al. Genetic diversity of Colletotrichum spp. Causing strawberry anthracnose in Zhejiang, China. Plant Dis, 2020; 104: 1351-1357. DOI: 10.1094/PDIS-09-19-2026-RE

[65] Grellet-Bournonville CF, Martinez-Zamora MG, Castagnaro AP et al. Temporal accumulation of salicylic acid activates the defense response against Colletotrichum in strawberry. Plant Physiol Bioch, 2012; 54: 10-16. DOI: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2012.01.019

[66] Tomas-Grau RH, Di Peto P, Chalfoun NR et al. Colletotrichum acutatum M11 can suppress the defence response in strawberry plants. Planta, 2019; 250: 1131-1145. DOI: 10.1007/s00425-019-03203-5

[67] Salazar SM, Grellet CF, Chalfoun NR et al. Avirulent strain of Colletotrichum induces a systemic resistance in strawberry. Eur J Plant Pathol, 2013: 135: 877-888. DOI: 10.1007/s10658-012-0134-y

[68] Racedo J, Salazar SM, Castagnaro AP et al. A strawberry disease caused by Acremonium strictum. Eur J Plant Pathol, 2013; 137: 649-654. DOI: 10.1007/s10658-013-0279-3

[69] Chalfoun NR, Grellet-Bournonville CF, Martínez-Zamora MG et al. Purification and characterization of AsES: A subtilisin secreted by acremonium strictum is a novel plant defense elicitor. J Biol Chem, 2013; 288: 14098-14113. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M112.429423

[70] Denoyes-Rothan B, Lafargue M, Guerin G et al. Fruit Resistance to Colletotrichum acutatum in Strawberries. Plant Dis, 1999; 83: 549-553. DOI: 10.1094/PDIS.1999.83.6.549

[71] Pradhan, Mahesh. Fertilizers: challenges and solutions. United Nations Environment Programme. Accessed March 17, 2022. Available at https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/fertilizers-challenges-and-solutions

[72] Hanzen Z. Managing Strawberry Anthracnose. UT Extension. Institute of Agriculture. University of Tennessee. Accessed September 19, 2019. Available at https://extension.tennessee.edu/publications/Documents/W847.pdf

[73] Fungicide Resistance Action Group (FRAG-UK). Fungicide resistance management in soft fruit. Accessed 2022; Available at: https://projectblue.blob.core.windows.net/media/Default/Imported%20Publication%20Docs/AHDB%20Cereals%20&%20Oilseeds/Disease/FRAG/FRAG%20Fungicide%20resistance%20management%20in%20soft%20fruit%20(March%202022).pdf

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). This open-access article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Copyright ©

Copyright ©