Media Tracking of Early COVID-19 Rumors and Sentiments in Africa

James Ayodele1*, Benjamin Djoudalbaye2, Nekerwon Gweh2

1World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, Nasr City, Cairo, Egypt

2Division of Health Diplomacy, Policy and Communications, Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

*Correspondence to: James Ayodele, World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, Monazamet El Seha El Alamia Street, Nasr City, Cairo 11371, Egypt; Email: jamesfal@hotmail.com

DOI: 10.53964/jia.2023003

Abstract

Background: The increasing use of social media for discussing public health issues underscores the critical need for authorities to use digital tools for monitoring discussions and for risk communication during public health emergencies.

Aim: This paper presents findings from the digital monitoring of discussions, rumors, and misinformation about COVID-19 by the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) during the first few months of the pandemic using the digital rumor monitoring system.

Methods: Africa CDC tracked rumors and misinformation about the COVID-19 pandemic using the digital rumor monitoring system from March to November 2020. Traditional media analysis was conducted using African media and human-curated aggregation of open-source content from various African sources. Social media analysis was conducted using geo-located African Twitter and Facebook sources, resulting in a set of content from the media.

Results: Critical sentiments regarding the COVID-19 pandemic were observed in Africa between March and September 2020, which drove rumors, misinformation, criticisms, and resistance to response effort. Key among these were sentiments against government and health authorities, sentiments regarding the existence of COVID-19, sentiments towards alternative medicine or organic cure for COVID-19, sentiments against the strict prevention measures, sentiments regarding the use of hydroxychloroquine, and sentiments against the World Health Organization.

Conclusion: These findings are of significance to public health authorities and decision-makers in Africa. As they focus on providing medical solutions through laboratory tests, treatment, and vaccination during public health emergencies, they need to invest in similar platforms to generate evidence for risk communication and community engagement. They should include digital monitoring of public health discussions as an essential part of public health response.

Keywords: COVID-19, sentiments, misinformation, rumors, social listening, Africa

1 INTRODUCTION

Social media has become a major platform for the discussion of public health issues globally and has been used extensively to spread information, rumors, misinformation, and disinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic[1]. Social media allows users to speak freely and express their disgust, sadness, anger, disappointment, or approval of public health policies and practice[2]. The increasing use of social media underscores the critical need for health authorities in Africa to advance its use as a medium of communication and the need to invest in digital monitoring of discussions so they can provide real-time response[3].

Digital platform offers the possibility of listening to discussions online and analyzing them to know how to target communication in real-time. It has become an effective tool for receiving feedback from communities about public health occurrences and interventions. This technology is currently evolving and it is already being used by institutions to monitor public health discussions[4,5].

This paper presents findings by the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) from monitoring COVID-19 discussions during the first few months of the pandemic using the digital rumor monitoring system. There was substantial coverage of vaccine sentiments, which, however, is covered in another report.

2 METHODS

In 2020, Africa CDC established a digital rumor monitoring system to track public discussion of the COVID-19 pandemic across Africa and provide evidence for targeting response. The system was based on Novetta’s Rapid Narrative Analysis[6], which used human observation and machine learning to provide insight about specific social conversations over a geographical location and a range of issues. Using custom queries developed by combining Boolean keyword matching and metadata of self-identified African users, the system tracked COVID-19 discussions on Facebook, Twitter and traditional media from March to November 2020. Using geo-located African Twitter sources resulted in a set of content from the media; quote-level metadata were then added in the framework, and results were culled on the basis of relevance. Weekly reports and trend analyses were generated for traditional and social media mentions of the COVID-19 pandemic. Discussions about several issues or sentiments were segregated and used for this report.

Traditional media analysis was conducted using African media and human-curated aggregation of open-source content from key African sources. Article- and quote-level metadata were added to the framework of Novetta Mission Analytics, and results culled based on relevance. Social media analysis was conducted using geo-located African Twitter and Facebook sources. These platforms were chosen because they are among the most frequently used social media platforms in Africa; in fact Facebook was the most used at the time of developing the monitoring platform[7]. The Quote-level metadata was added to the framework of Novetta Mission Analytics, and results culled based on relevance.

Rumors were categorized into major, moderate, and minor, depending on whether they could cause harm, could stop people from accessing services, could cause conflict, could result in risky behaviors, could put frontline workers, partners and communities at risk, could stigmatize certain groups, or could pose a significant reputational risk. Major rumors included those considered to be of high-impact and required urgent attention, moderate rumors were considered concerning and having the potential for a lasting effect, and minor rumors included those with potential to develop and have serious consequences.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Major Rumors and Sentiments Tracked

3.1.1 Sentiments Against Government and Health Authorities

Positive and negative sentiments associating COVID-19 response with corruption and government cover-ups were consistently observed in multiple African countries, particularly Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, and Tanzania. These were driven mostly by hashtags #COVID19Millionaires and #ArrestCOVID19Thieves and questioned the daily COVID-19 data published.

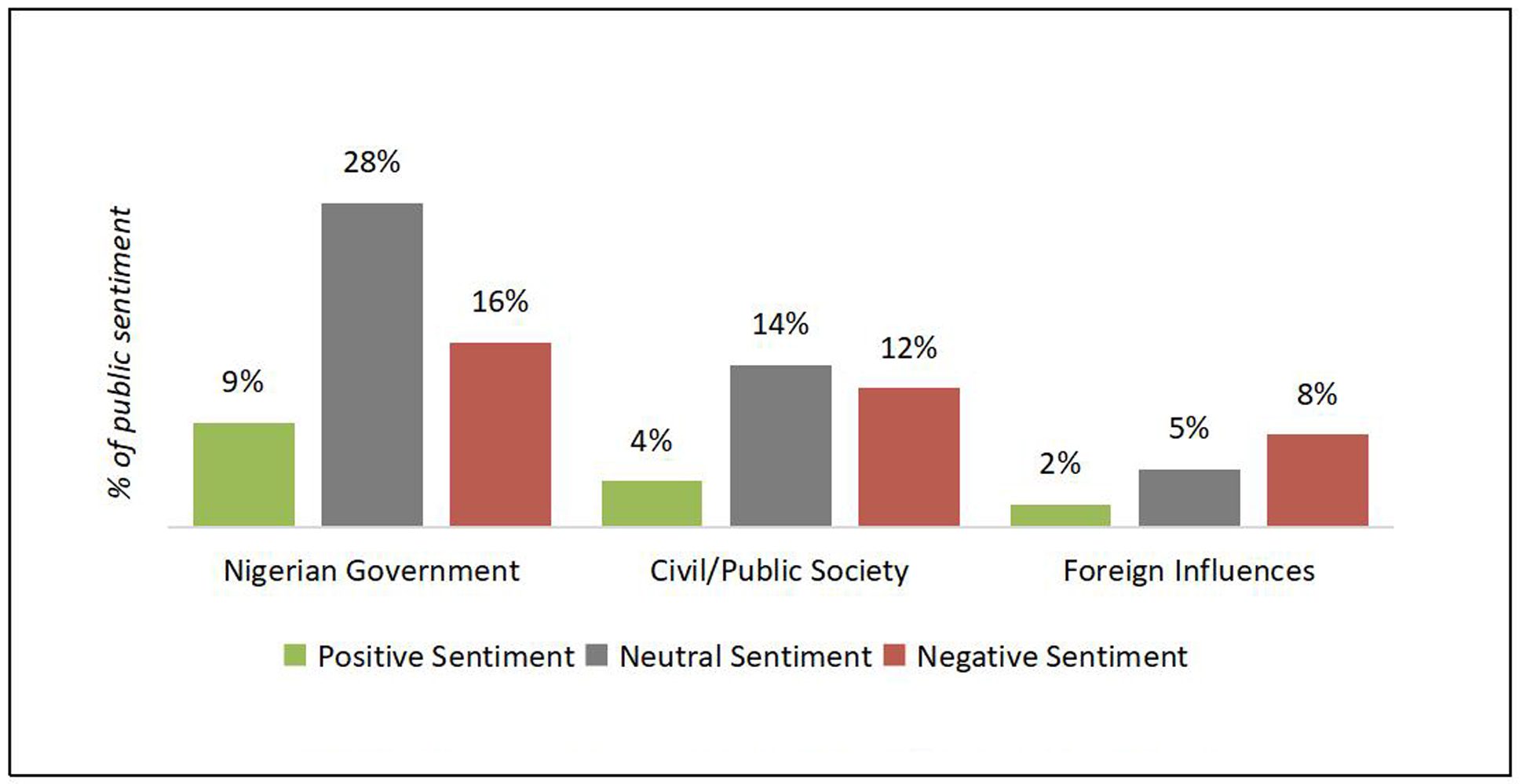

Rumors about fake COVID-19 cases and government corruption drove sentiments that COVID-19 was a business or government scam, reducing trust in African governments about COVID-19 case reporting. In Zambia, for example, citizens requested the names of “victims” to prove that the virus was real[8]. In Uganda, there was accusation of using COVID-19 funds to advance the government dictatorship agenda[9]. In Mozambique, there were rumors that doctors inflated case numbers to perpetuate COVID-19 “political scam”[10]. In Nigeria, negative sentiments towards the government, civil society, and foreign influences outweighed the positive (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1. Public sentiments in Nigeria against government, civil society and foreign influences, 20 April - 5 November 2020.

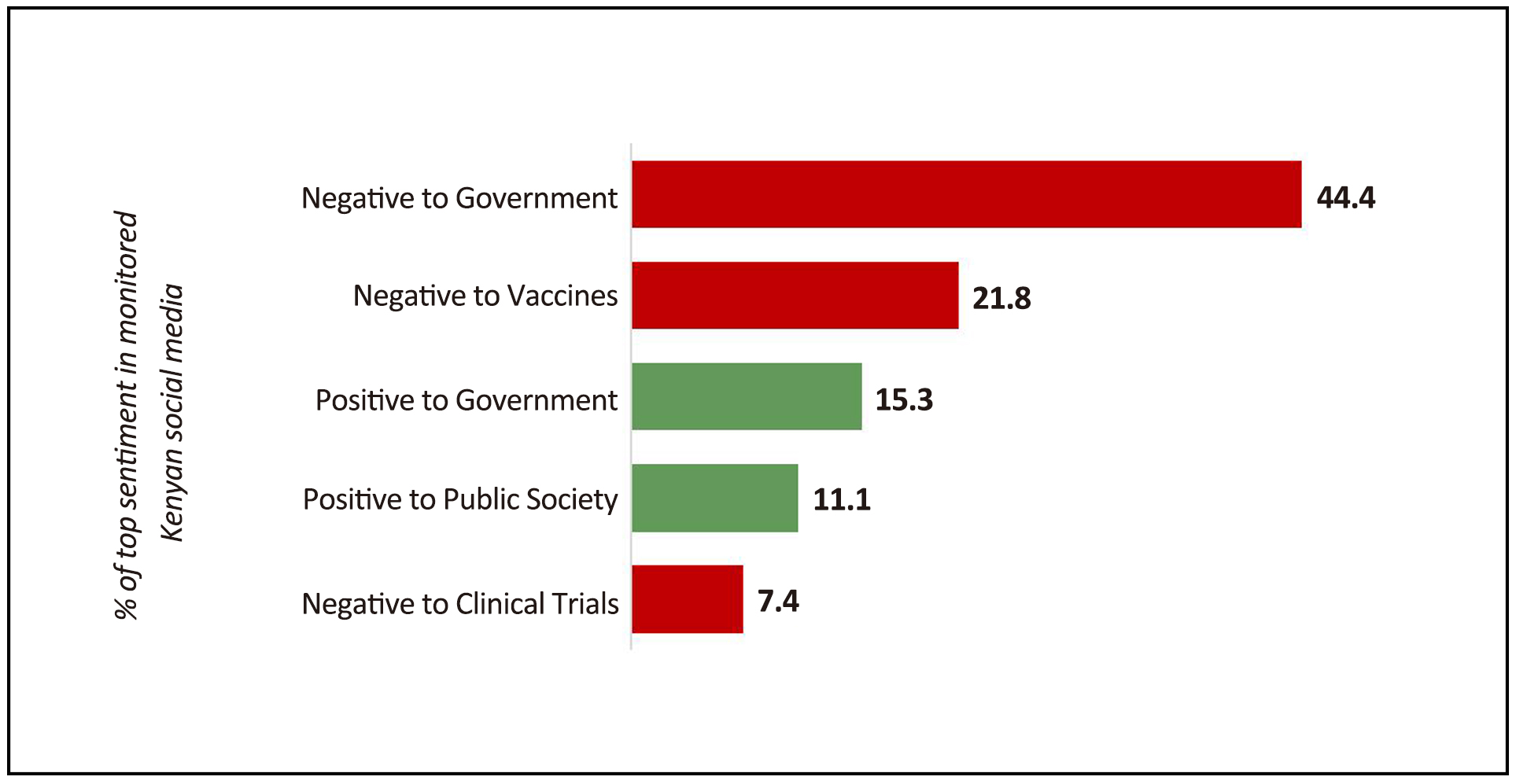

The strongest narratives against government and health authorities were observed in Kenya where social media users expressed concerns about misuse of the COVID-19 emergency response funds and accused the government of not providing free testing services (Figure 2). Negative messaging was found in comments on the Ministry of Health Twitter accounts[11].

Rumors regarding the misuse of COVID-19 funds by the Kenyan Government gained traction on traditional and social media in August 2020 following an investigative report that the Kenya Medical Supplies Authority (KEMSA) was colluding to sell to Tanzanian companies large portions of medical supplies donated by Jack Ma Foundation[12]. The investigation was launched after KEMSA and the Kenyan Government were accused of not accounting for KSh43 billion COVID-19 funds, leading to the emergence of the hashtag #COVID19Millionaires on Twitter and Facebook. Citizens blamed the government for arresting individuals who could not afford the face masks while donated masks were being sold[13,14]. An hour-long exposé on YouTube (no longer available) by NTV amplified media exposure and public discussions about business and government corruption[15].

Use of the #COVID19Millionaires hashtag peaked on 24 August 2020, after the Director of Public Prosecutions announced the prosecution of 5 administrators at Maasai Mara University, Kenya. The investigation had been in process since August 2019 and was not directly related to COVID-19.

A protest on 21 August 2020 at Uhuru Park, Nairobi, over the alleged misuse of COVID-19 funds in Kenya triggered tension and unrest on social media, leading to the emergence of the hashtag #ArrestCOVID19Thieves[16].

|

Figure 2. Top sentiments in Kenyan discussion of COVID-19, 15 September - 15 October 2020.

3.1.2 Sentiments Regarding the Existence of COVID-19

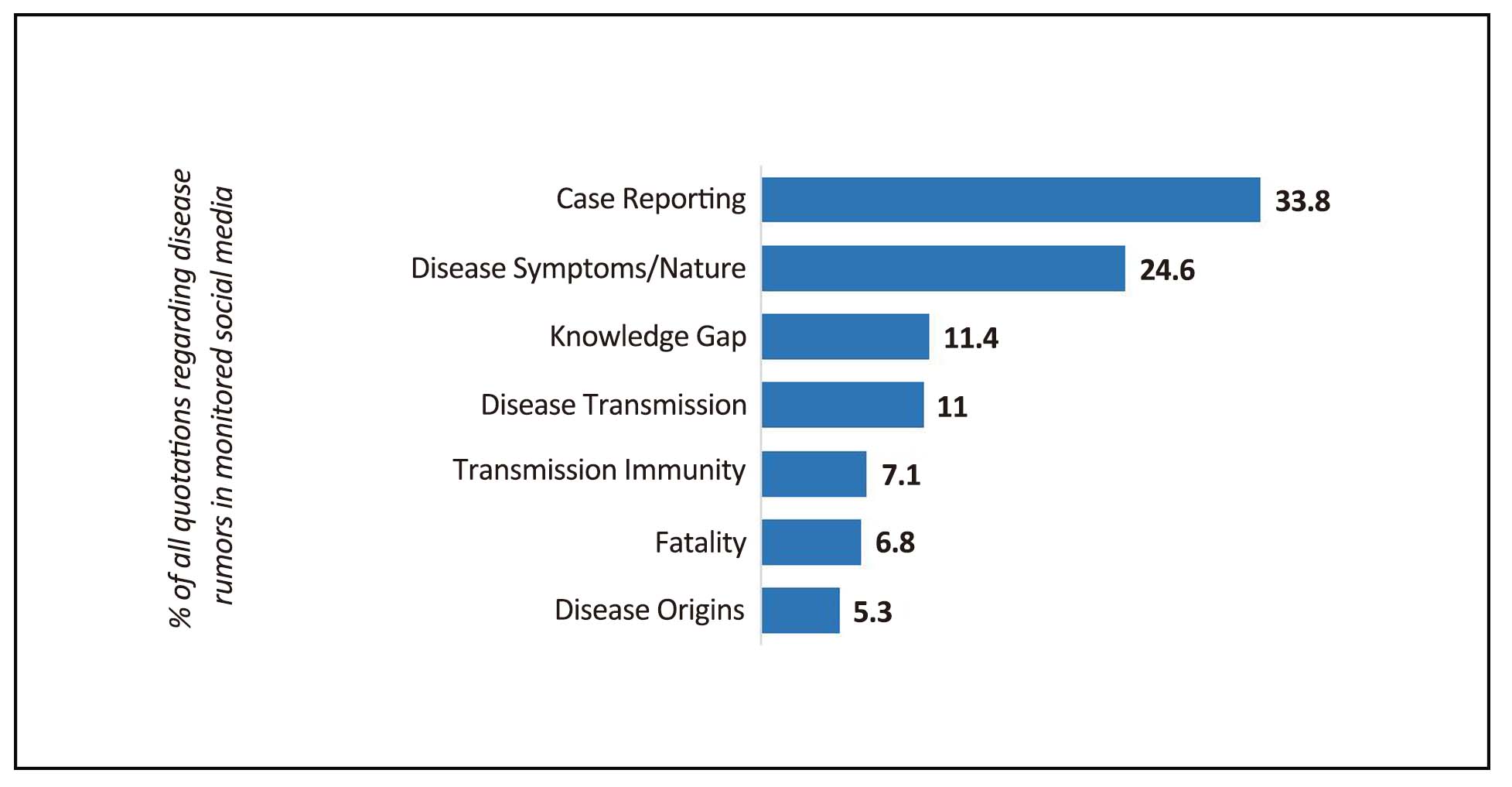

Public disbelief in the existence of COVID-19 drove further distrust in governments, healthcare workers, and public health organizations. From 1 to 20 June 2020 alone several narratives indicating disbelief in the existence of COVID-19 were observed across Africa (Figure 3). There was anger towards those not respecting physical distancing and comments that the virus did not exist. Misinformation increased through the circulation, recirculation, or repurposing of images, videos, and statements to fit certain narratives. For example, in Algeria, pictures of unmasked individuals sitting closely together in common use areas or public transport bolstered narratives that COVID-19 did not exist[17].

|

Figure 3. Key disease rumors across Africa, 1-20 June 2020.

Some social media users said the government was manipulating COVID-19 figures to attract sympathy and siphon public funds under the guise of procuring COVID-19 supplies. An example from Nigeria read: “COVID-19 has been controlled in Nigeria. I expected you to be talking about legally opening the state borders so life can start coming to normal again. The figures they post are not real, just because we overlook NCDC and the government doesn't mean we are fools...”[18]. Another one from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) (now deleted), read: “It is quite true, Ebola is more dangerous than COVID-19, malaria kills more than COVID-19, typhoid kills us every day but we are led to believe that COVID-19 is the most dangerous disease, which does not exist in the DRC”[19].

In October 2020, almost a year into the pandemic, a state governor in Nigeria said COVID-19 was “nothing but a glorified malaria disease being used to siphon billions of naira”[20]. A Facebook post from Guinea-Bissau (now deleted), read: “Guinean society understands that the new coronavirus does not exist and is based on the sole fact that the executive uses the pandemic to draw the attention of the international community with a view to mobilizing financial aid.”

In Algeria and Morocco, multiple posts of “coronavirus is a lie” were tracked, with some saying that COVID-19 was a biological weapon used in the war between States. This led the governments to make laws prohibiting the propagation of false information about the pandemic[21,22].

3.1.3 Sentiments Towards Alternative Medicine

African traditional and social media drew overwhelming attention to COVID-19 alternative / organic medicine. The most visible narrative related to COVID-Organics (CVO), an artemisia-based herbal extract promoted by the Republic of Madagascar.

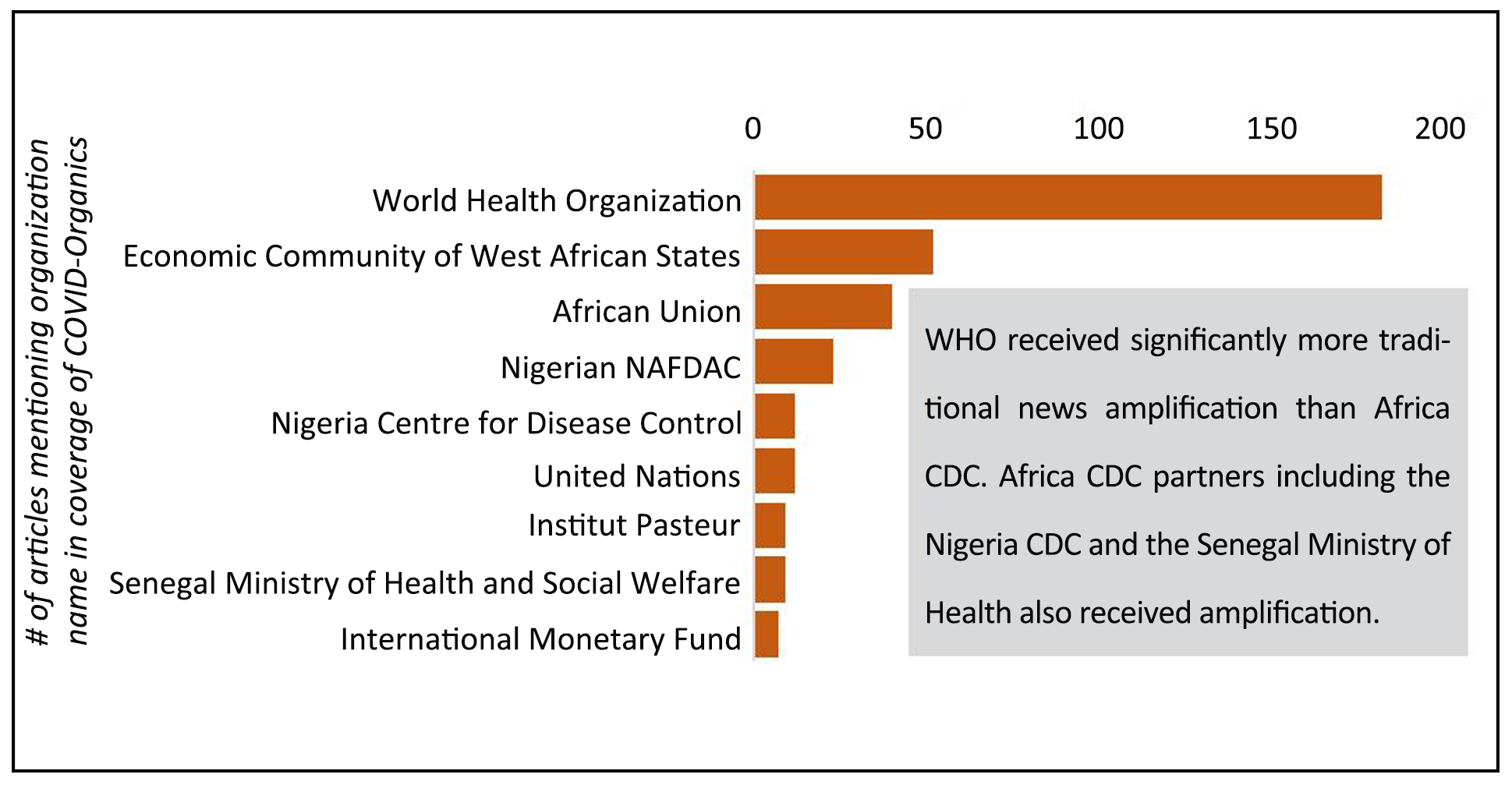

Media coverage of CVO surged in late April 2020 after the Malagasy President announced that Madagascar, in partnership with some unnamed foreign researchers, had developed CVO “preventative and curative” with “proven efficacy” against COVID-19 (Figure 4)[23]. Initial response to the promotion was mixed; about 40% of monitored social media users viewed it negatively, 21% were neutral, and 18% viewed it positively.

|

Figure 4. African traditional and social media coverage of COVID-Organics, 1 March - 30 September 2020.

Traditional media coverage spiked in May when some African governments, primarily in Central and Western Africa, expressed interest in CVO and the World Health Organization (WHO) Director-General said WHO would conduct trials on CVO (Figure 4). Traditional news coverage in French-speaking African countries, mainly Madagascar, DRC, Senegal, and Cote D’Ivoire, accounted for 53% of monitored traditional news. However, only 32% of monitored Twitter discussion was in French, while 63% was in English[24-29].

Social media coverage of CVO was high in DRC; tweets from Congolese users accounted for 3.3% of all geolocated African Twitter discussions of CVO in May 2020, surpassed only by tweets from South Africa, Nigeria, Kenya, and Ghana. The top Twitter users who propagated positive coverage of CVO in the DRC were the Goma-based youth group La Lucha and Dr Pika Longila, member of Jeunes Visionnaires and Foundation Bokomo, and representative of Sierra Leone-based La Maison de l'Artemisia[30,31]. Social media users shared interviews on CVO by Radio-Télévision Nationale Congolaise and Radio Okapi.

Sentiments about CVO and social media coverage waned in July 2020 (Figure 4) following reports of COVID-19-related deaths in Madagascar despite taking the herbal drink for treatment. On 10 July 2020, Madagascar reported a 52% increase in COVID-19 cases and 33 deaths in one week, and in August 2020 more than 13 000 cases and 162 deaths[32,33]. Subsequently, popular sentiment toward CVO remained largely positive for an “African” alternative.

The prominence of CVO served as foundation for the promotion of other untested treatments, including antivirus-COVID-19 syrup from São Tomé and Príncipe[34], clover juice from Egypt[35], achu soup from Cameroon[36,37], sawa sawa from Uganda[38], COVIDOL from Tanzania, and many others[39-42]. There was public approval for the use of garlic, pepper, onion, ginger, Cannabis in Zimbabwe, and ogogoro (local alcohol) in Nigeria to strengthen the immune system against COVID-19[43]. Perceptions about the drinking of alcohol as a preventive measure was observed across the continent because of the recommendation of alcohol for hand hygiene.

3.1.4 Sentiments Against the Strict Prevention Measures

Sentiments against the strict lockdown rules were highly negative, leading to increased disapproval and reduced trust in governments globally. Individuals and groups denounced the decision to close places of worship, entertainment centers, restaurants, and businesses with inciting rhetoric, which persisted for a very long time, beyond the period of this analysis.

South Africans perceived the lockdown and the ban of alcohol sales as part of a political agenda. One Twitter user said: “… Our government-imposed measures are the strictest in the world and set out to usher in their communist agenda. We will become a slave labor camp for China because of a projected 50% post-COVID unemployment rate”[44].

In Algeria, Facebook users reacted negatively to news of closing of the Drâa Ben Khedda fruit and vegetable market, stating that there was no COVID-19 in Algeria[45]. In the Republic of The Congo, some citizens believed that COVID-19 was a pretext to “properly control the movement of the population”[46].

One Twitter user in Kenya said: “COVID is here and it’s not ending soon. Locking down the country again or closing schools will only worsen the situation”[47]. A Twitter user in Eswatini said: “We will be killed by hunger before the #coronavirus gets us. Over 18,000 workers in Eswatini’s textile and garment sector have not been paid since the lockdown began. Workers have no money to buy food, pay rent, bills and other basics[48].” And Facebook users in Zambia said: “There is no Corona.... Just open everything and let us go back to work”[49], “Our COVID-19 isn't lethal”[50].

3.1.5 Sentiments Regarding the Use of Hydroxychloroquine

In May 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration approved emergency use of hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19 and later withdrew the approval after a large study found no evidence that hydroxychloroquine could stop deaths or help people with COVID-19 get better faster[51,52]. Subsequently, mentions of hydroxychloroquine as a cure dominated African Twitter discussions in the last two weeks of May 2020. Nigeria had the highest number of tweets (13,369), followed by South Africa, Tanzania, and Cameroon, with 6500+ tweets each. These mentions fuelled positive sentiments towards hydroxychloroquine and African social media users viewed the use of antimalaria drugs against COVID-19 as a success story and thought people who lived in areas with high malaria transmission and have been taking antimalaria drugs were immune to COVID-19[53].

There was a consequent increase in the sales of chloroquine and higher, uncontrolled dosing without regard for side effects. Several health authorities in Nigeria warned against large purchases and use of hydroxychloroquine to treat COVID-19, however, these warnings drew negative sentiments that it was a plot to force people to take COVID-19 vaccine. A Twitter user said[54]: “Funny how when the drug was being administered to millions of Africans as a malaria drug, these risks didn't seem to both…; Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine-antimalaria drugs Trump has touted for treatment of COVID-19 - were linked to an increased risk of death and heart ailments in a study”[55]. The mass reactions on social media were exacerbated after a US-based Nigerian doctor claimed that she had treated over 350 COVID-19 patients with a combination of hydroxychloroquine, zinc and Zithromax[56].

In May and June 2020, sentiments shifted towards WHO, when African social media users accused WHO of not protecting the interest of the developing countries as they struggled to find a cure for COVID-19. Public resentment was in response to warnings by WHO officials against unauthorized and unprescribed use of hydroxychloroquine and that the Madagascar CVO had not been tested and approved for use. African social media users felt WHO was not accepting CVO as a cure for COVID-19 because it was from Africa[57-59].

In South Africa, WHO was subsequently nicknamed “World Hell Organization” and some citizens cited the low death rates in Africa as proof that COVID-19 is a WHO hoax and that WHO had paid for Google advertisements regarding its vaccine campaigns to keep citizens in fear[60,61]. In DRC, WHO was accused of being a “conduit of global organized criminals who profit from the bloody pharma-trade” (post now deleted).

Other messaging on social media labeled WHO and US CDC as bioterrorists using the #BioTerrorists hashtag. Some African social media users said WHO was financed by big economies and would certainly protect the interests of those economies only. They perceived WHO as a political machinery financed and governed by developed nations that does not want treatment to originate from cheap ingredients from developing countries[62]. Some falsely claimed WHO had offered money to Madagascar to dump CVO and that Madagascar had pulled out of WHO due to disagreements over CVO[63].

3.2 Tracked Messaging and Response

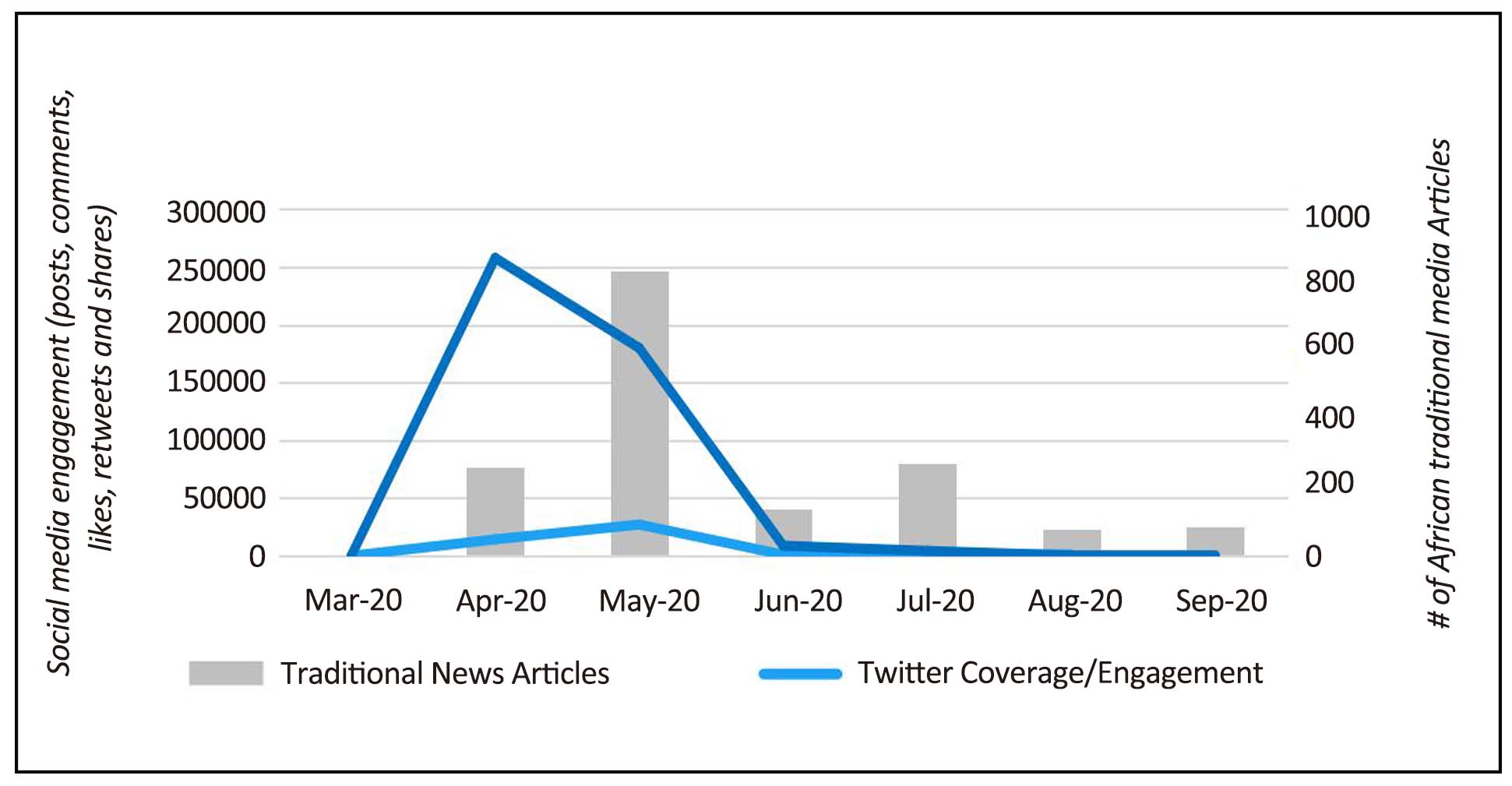

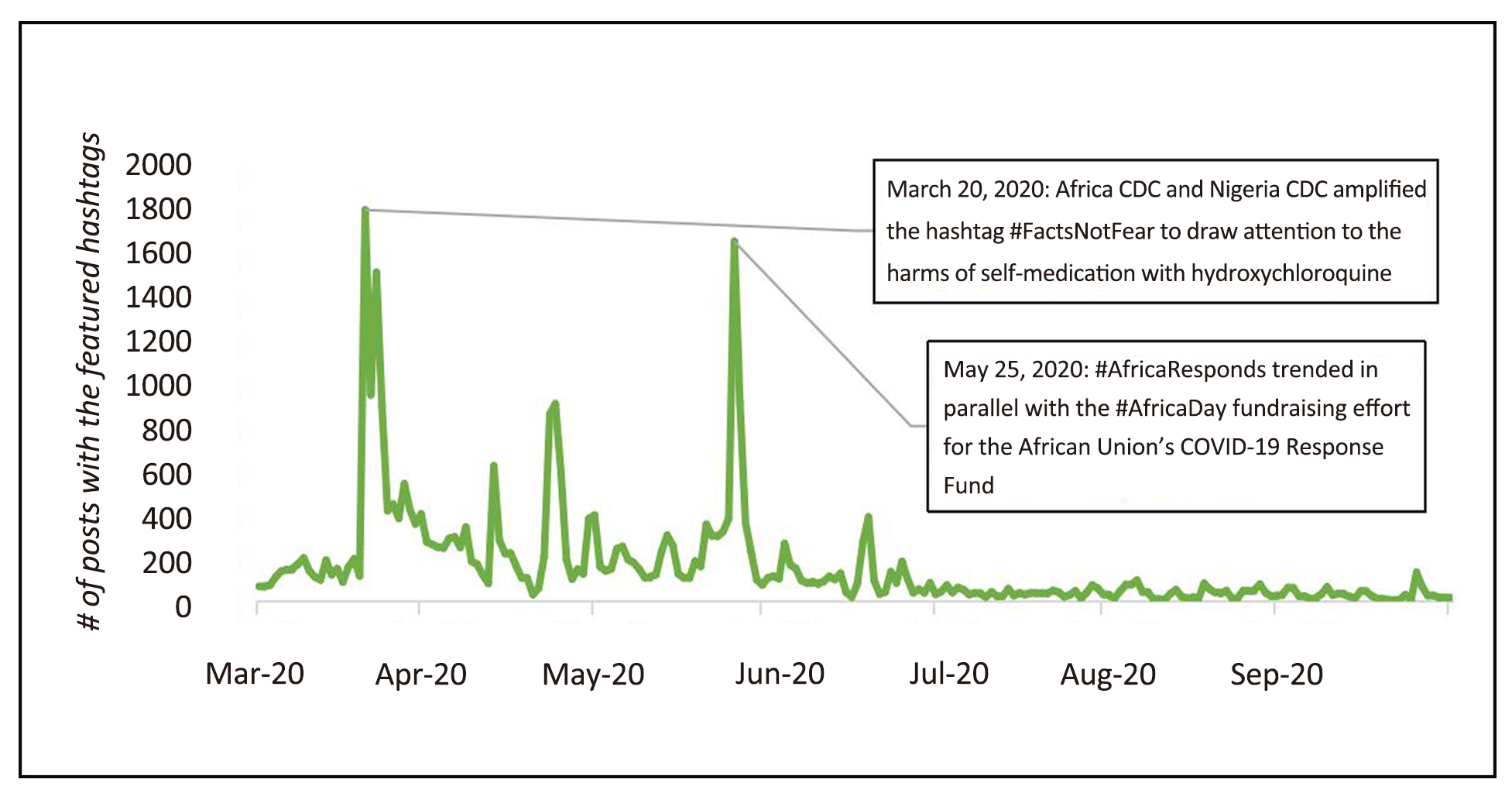

Africa CDC consistently used the social media for messaging in response to the rumors and misinformation relating to COVID-19, using featured hashtags: #TargetCOVID19, #AfricaResponds, #GetTheFacts, and #FactsNotFear. The hashtags demonstrated viral penetration in the media and were used in cross-messaging campaigns with United Nations organizations, WHO, and partners (Figure 5).

|

Figure 5. Social media posts containing Africa CDC featured hashtags, 1 March - 30 September 2020.

Africa CDC directly responded to some major rumors with information, visuals and short videos that gained traction and exposure on Facebook and Twitter. The information materials were developed in partnership with Facebook, One by One Target campaign, and other partners[64]. User engagement was more evident on Africa CDC’s Facebook page than the Twitter feed, although the same messages were shared on both platforms.

Africa CDC and WHO engaged the traditional media through their weekly press briefings, leading to amplification of statements, press releases, updates, and other materials relating to COVID-19. Africa CDC was mentioned in more than 40 traditional news articles, and most quoted, in early May 2020 after stating that it had communicated with the Malagasy Embassy in Ethiopia to request scientific data on safety and efficacy of CVO.

Response to sentiments regarding CVO by international organizations, governments, and health authorities peaked in April and May when interest in CVO increased (Figure 6). In September 2020, WHO, Africa CDC, and the Department of Social Affairs of the African Union Commission inaugurated a panel of experts which endorsed a protocol for testing herbal remedies for COVID-19 from Africa[65,66]. News of the inauguration led to a return of rumors and misinformation regarding the success of herbal remedies such as CVO. Some social media users perceived the news as an endorsement by WHO of the Madagascar treatment with tweets such as “Madagascar your time is now!!!”[67].

|

Figure 6. COVID-Organics messaging on traditional media in Africa, 1 March - 30 September 2020. Note: African Union messaging included and was mostly from Africa CDC.

WHO messaging in response to CVO and other alternative remedies received significant coverage in traditional media. Statements by the Director of WHO / AFRO stating that, “we are not discouraging the use of CVO but would like to advise that it be tested” and by WHO Director-General promising to discuss trials and data on CVO with the Malagasy Government were widely publicized[68,69]. Messages offering to “grant support to traditional medicine practitioners in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic” and to “recommend it for fast-tracked, large-scale local manufacturing” were widely shared in Nigerian and South African[70,71].

4 DISCUSSION

Targeting communication and community engagement during public health emergencies is challenging because of the difficulty in obtaining relevant evidence. Experts sometimes rely on assumptions when they are unable to meet and interact with the affected communities. However, the emergence of digital software that can track discussions over traditional and social media has made it possible to gather evidence online to inform communication interventions, as was the case during COVID-19 lockdown.

The narratives observed over social and traditional media showed knowledge gaps and have been instrumental in driving sentiments about several issues. The aggressive response to rumors and misinformation about the COVID-19 pandemic observed in this analysis highlights not only the disbelief in the reality of COVID-19, but also the distrust for government and health authorities, an indication of the longstanding lack of public trust in government and public officials[72]. Social media user narratives expressed disgust, sadness, anger, and disappointment at the multiple allegations of corruption scandals during COVID-19 pandemic, making the believe in the existence of COVID-19 to wane and making citizens think that COVID-19 is a scam.

In early May, the Malagasy president promoted the herbal drink, CVO, which drove high volume discussions on African traditional and social media[73]. Discussions about CVO declined toward the end of May and other treatment claims followed the same trend-based pattern, with each sentiment losing traction in favour of another. This shows the strong influence social media has on public health rumors, information, and misinformation[1]. Although many of these rumors were short-lived, they had great potential for negatively influencing response.

As COVID-19 coverage continued to serve as a platform for rumors and misinformation, minimal responses from public health authorities and governments allowed rumors to gain traction and fill information gaps. The limited and slow pace in responding gave opportunity for rumors and misinformation to become entrenched in the public narrative and serve as additional obstacles to control efforts.

Information provided by some government authorities on their social media pages was often basic and mostly about case counts, making them to become key targets of public criticisms[18]. Social media users responded negatively to case report statistics, accusing the government of spreading anxiety-inducing news. Others asked for more communication and interpretation of the COVID-19 statistics[74]. Comments such as “What’s the plan?” and “Take responsibility” on infographics reporting cases or reminding the public to observe prevention measures suggest that the public wanted guidance or information which they were not receiving[75].

The use of social media for messaging allowed Africa CDC, WHO, and other institutions to respond to COVID-19 rumors and misinformation, with cross-messaging across the continent. The posts drew tens of thousands of reactions, indicating that a large and engaged audience was being reached. The consistent use of hashtags helped amplify messages, thus gaining significant viral penetration on social media. However, these messages were often not early enough to address the rumors and could have attracted significantly higher interactions with more intense and more sustained use.

Traditionally, public health risk communication is often informed by direct interactions with target communities. However, in a lockdown situation like in 2020 and over a very large geographical area like Africa, it becomes very difficult or impossible to get reliable information through such interactions. This therefore makes digital social monitoring very important to public health. Authorities often want to play safe by staying away from controversial comments on social media, however, it has become imperative to begin monitoring public health discussions in real-time online so that authorities can respond appropriately and in time before such rumors and misinformation become endemic. This was not the case in 2020. The high rate of anti-vaccine and COVID-19 rumors and misinformation observed online can be partly attributed to health authorities' inaction, neglect, or delayed response.

This analysis has some limitations. It focuses mainly on discussions over traditional media, Facebook, and Twitter, with little reference to some YouTube posts. It does not consider discussions over other social media platforms like Instagram, Tik Tok, LinkedIn, Snap Chat, etc. This may have limited the richness of information obtained. Due to the word limit, some sentiments observed over social media are not included in this report. Among these are sentiments about natural immunity to COVID-19, steam inhalation, COVID-19 and 5G networks, “death at home”, donated face masks and food aids, religious beliefs, age, and race[76-81].

5 CONCLUSION

This paper focuses on the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic and provides insight into discussions on selected issues of concern to the African public. The findings provide key lessons for planning communication response to future pandemics and public health emergencies. The sentiments observed highlight key issues affecting the success of public health communication during health emergencies in Africa: information gap, distrust in government and health authorities, controversies about excessive foreign influence on public health policy in Africa, and misunderstanding or misinterpretation of the intention of health interventions.

As authorities focus on providing medical solutions through laboratory tests, treatment, and vaccination, it is imperative to also invest in generating evidence to inform risk communication and community engagement for public health interventions. Some of the sentiments were addressed minimally and inadequately through campaigns or press briefings, however, several rumors remained unaddressed by the concerned authorities even when they were aware of them.

Tools for online monitoring of public health discussions are currently capital-intensive, but they are essential to enhance public health communication. Universal availability to the respective authorities of the digital tool for monitoring online discussions about public health issues is being advocated to enhance access to credible information and the effectiveness of public health communication.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the efforts of colleagues at Africa CDC who made this media monitoring possible, and partner staff who contributed to the creation and management of the platform, particularly Hana Rohan and Melody Sven. We thank Dr. Nicaise Ndembi for reviewing the article internally.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared that they had no conflict of interest.

Author Contribution

Ayodele J, Djoudalbaye B, Gweh N monitored the tracking dashboard and the reports and made weekly summary presentations on them to African Union Member States and partners. Ayodele J drafted the article and all authors reviewed and made their contributions to the content.

Abbreviation List

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CVO, COVID-organics

DRC, Democratic republic of congo

KEMSA, Kenya medical supplies authority

WHO, World Health Organization

[1] World Health Organization. WHO Director-General Statement on the Role of Social Media Platforms in Health Information. Accessed 28 August 2019, Available at: [Web]

[2] Tate J. The Health Policy Partnership. Can social media have a role in tackling vaccine hesitancy? Accessed 3 May 2019, Available at: [Web]

[3] Harvard TH. Chan School of Public Health. Establishing the truth: vaccines, social media, and the spread of misinformation. Available at: [Web]

[4] European Centres for Disease Prevention and Control. ECDC Technical Report, Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy. Stockholm, Sweden, February 2020. [DOI]

[5] Vaccine Confidence Project. Social media conversations and attitudes in the UK towards COVID-19. Available at: [Web]

[6] Novetta. Entity Analytics. Available at: [Web]

[7] Statcounter. Social Media Stats Africa, Jan-Dec 2020. Available at: [Web]

[8] Mwebantu. Several posts. Facebook, 13 June 2020. Available at: [Web]

[9] Bukenya Edrisa Kimbugwe. Uganda must pick a leaf again from our mighty neighbours and stop misusing their covid funds to finance the dictatorship. Facebook, 2 July 2020. Available at: [Web]

[10] Constantino Carvalho. A COVID 19 é uma farsa com fins politicos. Facebook, 18 August 2020. Available at: [Web]

[11] Dominic Omondi. The Standard Insider. Where they are holding Covid crisis billions. Accessed 23 July 2020, Available at: [Web]

[12] Tuko.co.ke. When it comes to embezzling funds and looting, the government never disappoints. Facebook, 17 August 2020. Available at: [Web]

[13] Michael Nganga. They stole donated PPEs. Facebook, 17 August 2020. Available at: [Web]

[14] Fickson Mwinamo. The blame goes to the civilians. Facebook, Available at: [Web]

[15] NTV Kenya, #COVID19Millionaires: Corruption and Covid-19 moving at the same pace. YouTube, 17 August 2020. Available at: [Web]

[16] Suspended account. Twitter. Available at: [Web]

[17] Actualité Tizi-Ouzou. Une photo qui nous est parvenue de la part d'un membre de la page. Facebook, 16 June 2020. Available at: [Web]

[18] Kaycee Ofurum. COVID-19 has been controlled in Nigeria. Facebook, 18 June 2020. Available at: [Web]

[19] Deleted Facebook post, 11 June 2020, Available at: [Web]

[20] Eniola Ankinkuotu. #EndSARS protest, looting of COVID-19 palliatives about 2023-Yahaya Bello. Accessed 27 October 2020, Available at: [Web]

[21] Luis Martinez. SciencesPo Center for International Studies. COVID-19 in Algeria: for whom does the bell toll? Accessed 27 April 2020, Available at: [Web]

[22] Yasmine Kacha. Amnesty International. In a post-COVID-19 world, “fake news” laws, a new blow to freedom of expression in Algeria and Morocco/Western Sahara? Accessed 29 May 2020, Available at: [Web]

[23] Andry Rajoelina. Depuis sa création par le Pr Ratsimamanga. Twitter, 20 April 2020. Available at: [Web]

[24] #CovidOrganics. Twitter, May 2020. Available at: [Web]

[25] Covid-Organics. Facebook, May 2020. Available at: [Web]

[26] Mwansa Kapyanga. Something is definitely very right about this herbal medicine. Twitter, 5 May 2020. Available at: [Web]

[27] Man’s NOT Barry Roux. As expected some Africans have already started discrediting the madagascar magic herbal drink named COVID-ORGANICS. Twitter, 3 May 2020. Available at: [Web]

[28] Siyanda Laminii. What power does the WHO have over a sovereign country. Twitter, 11 May 2020. Available at: [Web]

[29] eNCA. Madagascar is putting its controversial herbal remedy for #Covid19 on sale, despite warnings from the World Health Organization. Twitter, 10 May 2020. Available at: [Web]

[30] La Bénicienne. Twitter, Available at: [Web]

[31] Dr Pika~Longila. Twitter, May 2020. Available at: [Web]

[32] Raïssa Ioussouf. BBC News (Africa). Madagascar president's herbal tonic fails to halt Covid-19 spike. Accessed 14 August 2020, Available at: [Web]

[33] Felix Tih. Anadolu Agency. Nigeria: Madagascar’s herbal drink cannot cure COVID-19. Accessed 20 July 2020, Available at: [Web]

[34] Fédération Atlantique des Agences de Presse Africaines (FAAPA). Covid-19: Líder da medicina tradicional são-tomense lança xarope de plantas que diz “combater” coronavírus. Accessed 6 May 2020, Available at: [Web]

[35] Black Honey. Twitter, May 2020. Available at: [Web]

[36] Titanji VPK. COVID-19 Response: The case for Phytomedicines in Africa with particular focus on Cameroon. J Cameroon Academy Sci, 2021; 17: 163-175. [DOI]

[37] Julius Oben. Bantuvoices. Use of Improved Achu Soup against Covid-19: The potential of a Cameroonian Functional Food, ‘Achu Soup’ (Star Yellow) in managing the spread of Covid-19. Accessed 5 May 2020, Available at: [Web]

[38] Obaj Okuj. Eye Radio. Drug and Food Authority bans Sawa-Sawa drink. Accessed 3 June, 2020, Available at: [Web]

[39] TBConline. Dawa ya covidal yaleta mtafaruku kwenye kutibu CORONA. YouTube, 11 May 2020. Available at: [Web]

[40] Kamala James. Tanzanian generated herbal remedy-COVIDOL has continued to show its potency. Twitter, 28 August 2020. Available at: [Web]

[41] Aditi Chattopadhyay. The Logical India. Fact Check: Did Tanzania Find Herbal Cure For COVID-19? Accessed 17 June 2020, Available at: [Web]

[42] James Kamala. Daily News. COVIDOL Herbal Cure against Virus is Safe-Expert. Accessed 28 August 2020, Available at: [Web]

[43] Punch Newspapers. How Nigerians fighting COVID-19 with alcohol are becoming mentally ill. Accessed 30 August 2020, Available at: [Web]

[44] Rob Hutchinson. The situation in South Africa is dire. Twitter, 5 May 2020. Available at: [Web]

[45] Mohamed Ouarezki. C est grave ce qu ils font y on a pas de virus corona en Algérie. Facebook, 27 July 2020. Available at: [Web]

[46] Patrick MK. Le Coronavirus est devenu un prétextee pour bien controller les mouvements de la population. Facebook, 8 September 2020. Available at: [Web]

[47] Bina Maera. Covid 19 is here and it's not ending soon. Twitter, 22 May 2020. Available at: [Web]

[48] IndustriALL. We will be killed by hunger before #coronavirus gets us. Twitter, 6 May 2020. Available at: [Web]

[49] Precious Bwalya. There is no Corona imwee. Facebook, 15 June 2020. Available at: [Web]

[50] Kelvin Phumulo. Our Covid-19 isn’t lethal. Facebook, 16 June 2020. Available at: [Web]

[51] Marshall Cohen, Sara Murray. CNN. Bound by science, bent by politics: Inside the FDA's reversals and walk-backs as it grapples with the coronavirus pandemic. Accessed 29 May 2020, Available at: [Web]

[52] WebMD. The FDA approved emergency use of hydroxychloroquine. Twitter, 16 August 2020. Available at: [Web]

[53] Amdi. The amount of anti-malaria medications in an average African man’s blood is enough vaccine to stop COVID-19. Twitter, 14 September 2020. Available at: [Web]

[54] Bloomberg Quicktake. Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine. Twitter, 22 May 2020. Available at: [Web]

[55] Rebecca Enonchong. Funny how when the drug was being administered to millions of Africans. Twitter, 22 May 2020. Available at: [Web]

[56] Lara Adejoro. Healthwise. Hydroxychloroquine use limited to clinical trials in Nigeria-NCDC. Accessed 28 July 2020, Available at: [Web]

[57] Lusakatimes.com. Green Party President Peter Sinkamba accuse WHO of frustrating efforts by African Countries to find a cure for the coronavirus pandemic. Accessed 6 May 2020, Available at: [Web]

[58] Felix Tih. Anadolu Agency. Madagascar slams WHO for not endorsing its herbal cure. Accessed 11 May 2020, Available at: [Web]

[59] Siyanda Laminii. What power does the WHO have over a sovereign country. Twitter, 11 May 2020. Available at: [Web]

[60] Tumi Lephalala. So in 2016 Bill Gates talked about an epidemic must be made. Facebook, 26 August 2020. Available at: [Web]

[61] Barend Du Plessis. The low corona death toll in Africa is proof of this WHO hoax. Facebook, 8 September 2020. Available at: [Web]

[62] Hemraj Singh. OMS is financed by big economies and would certainly protect their interest. Facebook, 23 May 2020. Available at: [Web]

[63] Dubawa. Premium Times. The facts about Madagascar-quitting WHO, and a $20million offer to poison Covid-organics. Accessed 28 May 2020. Available at: [Web]

[64] One by One: Target 2030. Available at: [Web]

[65] World Health Organization. Expert panel endorses protocol for COVID-19 herbal medicine clinical trials. Accessed 19 September 2020, Available at: [Web]

[66] BBC News (Africa). Coronavirus: WHO sets rules for testing African herbal remedies. Accessed 20 September 2020, Available at: [Web]

[67] A.A Nangolo. Madagascar your time is now. Twitter, 21 September 2020. Available at: [Web]

[68] Adam Vaughan. NewScientist. No evidence 'Madagascar cure' for covid-19 works, says WHO. Accessed 15 May 2020, Available at: [Web]

[69] Felix Tih. Anadolu Agency. WHO holds meeting with African traditional medicine experts. Accessed 12 May 2020, Available at: [Web]

[70] Fatima Khan. IOL. WHO woos traditional medicine in Africa’s Covid cure search. Accessed 27 September 2020, Available at: [Web]

[71] Nigeria Health Watch. Can drinking alcohol prevent or cure COVID-19? Accessed 13 July 2020, Available at: [Web]

[72] OECD. Tackling coronavirus (COVID-19): contributing to a global effort. Transparency, communication and trust: The role of public communication in responding to the wave of disinformation about the new coronavirus. Accessed 3 July 2020, Available at: [Web]

[73] Andry Rajoelina. Depuis sa création par le Pr Ratsimamanga. Twitter, 20 April 2020. Available at: [Web]

[74] Henry Abuya. Provide good communication between the scientific community and the Kenyan public. Twitter, 22 July 2020. Available at: [Web]

[75] Citizen Reporter. Citizen Digital. WHO Says Drop In COVID-19 Cases In Kenya A Result Of Low Testing, Contact Tracing. Accessed 31 August 2020, Available at: [Web]

[76] ElDostor News. Professor “Sadr”: The Egyptians gained immunity, and the majority took a mild corona. Facebook, 22 July 2020. Available at: [Web]

[77] I Know. This is the reason for the danger of using the 5G network. YouTube, 23 January 2020. Available at: [Web]

[78] George Kegoro. Death at home from Covid 19 is logical. Twitter, 18 May 2020. Available at: [Web]

[79] Imran Dideh Pentagone. Il ne faut pas utiliser nouveaux masques et gels qui on ete fournis comme aide par le gouvernement Francais. Facebook, 2 July 2020. Available at: [Web]

[80] Teresia Bosibori. We continue denouncing those words in Jesus name. Facebook, 22 Augist 2020. Available at: [Web]

[81] Faizal. Tanzanians found out that the testing kits came with covid-19. Twitter, 23 August 2020. Available at: [Web]

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). This open-access article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Copyright ©

Copyright ©