Immunotherapy for Colorectal Cancer: Recent Advancements

Shaik Fariha Kaunain1, Ashok Kumar Pandurangan1*

1School of Life Sciences, B.S. Abdur Rahman Crescent Institute of Science and Technology, Vandalur, Chennai, India

*Correspondence to: Ashok Kumar Pandurangan, PhD, Associate Professor, School of Life Sciences, B.S. Abdur Rahman Crescent Institute of Science and Technology, Seethakathi Estate, GST Road, Vandalur, Chennai 600 048, India; Email: panduashokkumar@gmail.com

DOI: 10.53964/id.2025012

Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. Despite advancements in screening and treatment, the 5-year survival rate of metastatic CRC patients remains low. Immunotherapy has emerged as a promising approach to treat CRC by harnessing the immune system to target cancer cells, while sparing healthy tissues. This review discusses current immunotherapeutic strategies for CRC, including immune checkpoint blockade (ICB), adoptive cell therapy (ACT), monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), oncolytic viruses, cancer vaccines, and immunomodulatory drugs. ICB therapies, such as anti-PD-1/PD-L1 and anti-CTLA-4, have shown efficacy in microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) CRC patients, but remain limited in microsatellite stable cases. ACT, including tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte and CAR-NK cell therapies, has demonstrated potential in clinical studies. mAbs, such as cetuximab and bevacizumab, continue to be the mainstay of treatment, while bispecific antibodies (bsAbs) show promise in combination with anti-PD-1 therapies. Oncolytic viruses and cancer vaccines have shown variable results in CRC. Interleukins (ILs) and interferons (IFNs) play a role in modulating the immune response, with IL-2, IL-12, and IFN-γ exhibiting anti-tumor effects. Immunomodulatory drugs, such as thalidomide and maraviroc, augment anti-tumor effects by modifying immunological function. Despite progress, challenges remain in optimizing and expanding the use of immunotherapy for all subgroups of patients with CRC. Future directions include combination treatments, tumor microenvironment modification, personalized tumor vaccines, and development of predictive biomarkers to guide patient selection and treatment planning.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, immunotherapy, immune checkpoint blockade, adoptive cell therapy, monoclonal antibodies, oncolytic viruses, cancer vaccines

1 INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the most common cancer worldwide and is responsible for most cancer-related fatalities. Usually, carcinogenesis starts in the mucosa of the colon, where epithelial cells can produce benign lesions that can develop into cancer due to changes in DNA caused by carcinogens[1,2]. Chromosome instability, hypermethylation of CpG islands, and mutations in mismatch repair genes such as APC, DCC, P53, and K-ras are all important biological mechanisms. In the early stages, CRC is limited to the mucosa and submucosa, with only 10% of patients experiencing lymphatic involvement[3]. Dysbiosis aids in the progression of cancer, and the gut microbiota plays a crucial role in the development of CRC[4]. As the condition progresses, the symptoms include unexplained weight loss, changes in bowel habits, chronic stomach pain, and systemic symptoms[5]. Imaging tests (CT and MRI), endoscopy, and biomarker analysis (stool and circulating tumor DNA) are used for diagnosis. Despite the development of non-invasive tests, such as fecal immunochemical tests, colonoscopy remains the most effective screening method[6]. Approximately 90% of CRCs are adenocarcinomas that can present with ulcerations, elevations, or infiltrations. Radiation, chemotherapy, surgery, and immunotherapy are treatment options, and in advanced cases, immunotherapy has been shown to prolong survival. Additional supportive care can also help manage symptoms and improve the quality of life[3].

In terms of treatment options, surgery and chemotherapy are commonly used practices. The serious side effects of chemotherapy has directed researcher’s turn into the natural products as a better candidate for treating CRC. Natural products have shown promising potential in the prevention and treatment of CRC. Several plant-derived compounds have demonstrated anti-cancer effects through various mechanisms. For example, curcumin from turmeric has been found to inhibit cell proliferation and induce apoptosis in CRC cells[7,8]. Vernodalin, a sesquiterpene lactone isolated from Vernonia amygdalina, has demonstrated promising anti-cancer effects against CRC in preclinical studies. Research has shown that vernodalin can inhibit colon cancer cell proliferation and induce apoptosis through multiple mechanisms. It has been found to downregulate key oncogenic pathways like NF-κB and activate pro-apoptotic proteins such as caspase-3[9]. Resveratrol, found in grapes and berries, exhibits anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties that may help suppress tumor growth[10]. Epigallocatechin gallate from green tea has also shown anti-cancer activity by modulating multiple signaling pathways[11]. Other natural compounds like quercetin, sulforaphane, and gingerol have demonstrated the ability to inhibit cancer cell growth and metastasis in preclinical studies. While more clinical research is needed, these natural products offer potential as chemopreventive agents or adjuvants to conventional CRC therapies due to their multi-targeted effects and generally low toxicity profiles.

On the other hand, the immune system plays a crucial role in CRC development, progression, and treatment. Here are some key points about the role of the immune system in CRC. The immune system normally detects and eliminates abnormal cells, including early cancer cells. However, cancer cells can develop mechanisms to evade this surveillance. on the other hand, chronic inflammation in the colon can promote CRC development by creating a tumor-supportive microenvironment[12]. As CRC progresses, it creates an immunosuppressive microenvironment that inhibits anti-tumor immune responses. This includes recruitment of regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). Immune checkpoint proteins: CRC cells can express proteins like PD-L1 that inhibit T cell responses. Blocking these checkpoints with immunotherapy can reactivate anti-tumor immunity. Understanding these complex interactions between the immune system and CRC is crucial for developing and optimizing immunotherapeutic approaches[13]. Ongoing research aims to enhance anti-tumor immunity and overcome immunosuppression in CRC.

2 IMMUNOTHERAPY

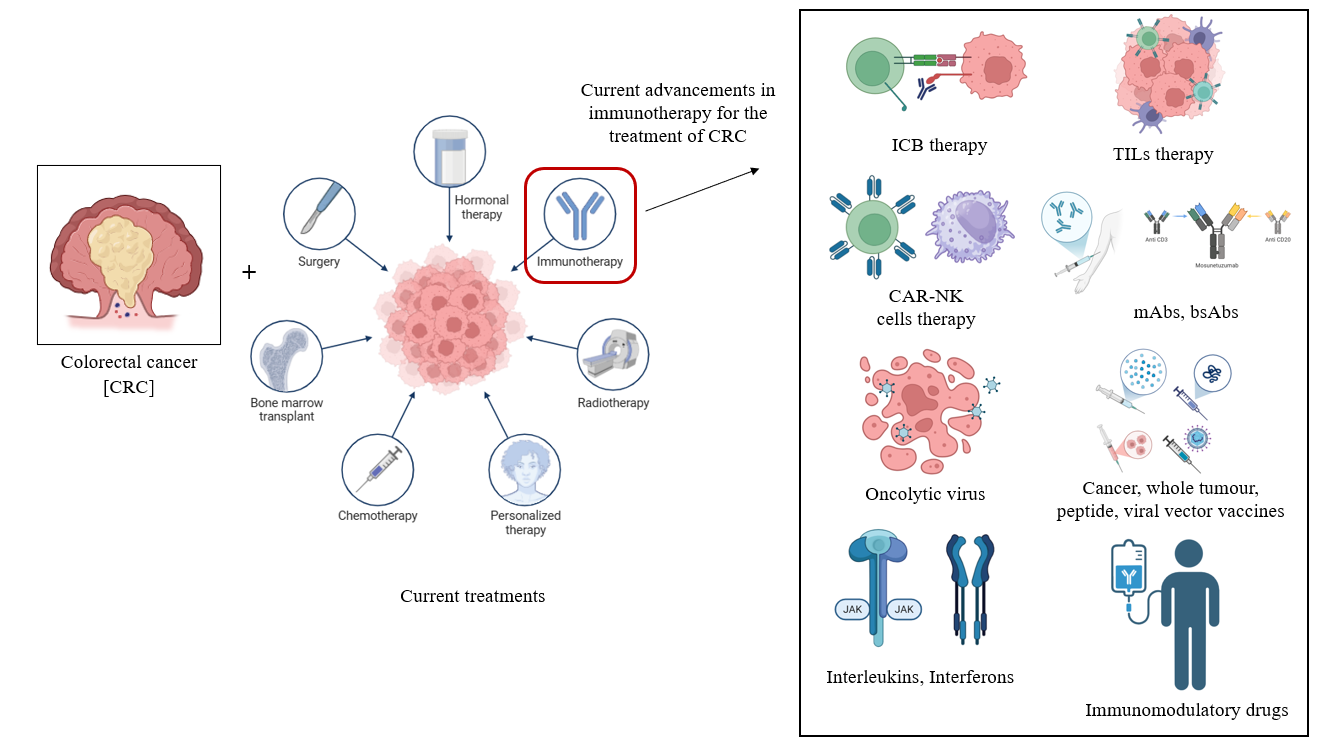

Immunotherapy is a key treatment for many immunological disorders, including immunodeficiencies, hypersensitivity reactions, autoimmune diseases, organ transplantation, malignancies, inflammatory disorders, and infectious diseases. It involves the use of drugs (e.g., immunosuppressants), biologics (e.g., cytokines, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), antisera), vitamins and minerals (e.g., zinc, vitamin C, and vitamin B6), bone marrow transplants, and vaccinations to control immunological responses. Immunotherapy treats immune-mediated disorders and enhances patient outcomes and quality of life by up-regulating or down-regulating the immune system[14]. Cancer treatments have shifted from surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and targeted therapies to immunotherapy, which reactivates the immune system to kill tumor cells. Unlike traditional therapies, immunotherapy modifies the tumor microenvironment by using cytokines, chemokines, and immune cells to prevent recurrence. The introduction of immunotherapy has changed cancer treatment with mAbs, small-molecule drugs, adoptive cell therapy (ACT), oncolytic viruses, and cancer vaccines[15]. Immune checkpoint inhibitors are game changers, and while single-agent inhibition was initially used, combination checkpoint blockade is increasingly being used to increase response rates by using complementary mechanisms of action. These inhibitors are also being combined with other treatments, such as chemotherapy, radiation, vaccines, and cytokines, to maximize efficacy. Many clinical trials have tested combination therapies with immune checkpoint inhibitors. However, few studies have demonstrated its clinical success[16]. Overcoming primary, adaptive, and acquired resistance is key to improving immunotherapy and obtaining better outcomes in a broader population of cancer patients (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1. The Mechanism of Immunotherapy to the Patients of CRC.

3 IMMUNOTHERAPY FOR THE TREATMENT OF CRC

Although conventional treatments like chemotherapy alone or along with other targeted therapy are fundamentally used in the treatment of mCRC, the development of resistance against standard therapy, the detrimental effects induced by cytotoxic drugs and the poor 5-year survival rates (13% for mCRC) have significantly intensified the search for targeted therapies for CRC[17]. Immunotherapy is promising because it activates the immune system to target the exact cancer cells while sparing healthy cells, particularly in patients with MSI-H tumors[18]. While some immunotherapies were highly successful, others were unsuccessful. Overall, successful immunotherapy improves the prognosis and quality of life in cancer patients[19]. Current immunotherapeutic treatments for CRC are outlined below.

3.1 ICB Therapy

Immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapy is among the therapies that have revolutionised the treatment of cancer over the past years by using the immune system to target the tumours. Approved first for advanced melanoma in 2011, the key molecules like CTLA-4, PD-1, PD-L1 and LAG-3 are targeted against the solid tumour[20]. For CRC patients, ICB therapies augment anti-tumour immune responses by inhibiting the binding of inhibitory receptors, including the most notably used anti-PD-1/PD-L1 and anti-CTLA-4 therapies, which are especially beneficial in the case of MSI-H CRC patients. Nevertheless, they remain limited to patients with microsatellite stable (MSS)-CRC, and systemic toxicities may include rashes and diarrhea to their use. Although such complications make combination methods impossible to enhance results, the specificity of ICB therapy and the number of drugs allow the combination method[21]. The research is ongoing to understand the molecular pathways of resistance and make the therapy more efficient by including novel drug combinations and specific biomarkers[20].

3.2 Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte Therapy

Tumour-infiltrating lymphocyte therapy is one of the emerging forms of ACT that has shown a promising response in cases with advanced melanoma, especially in the case of individuals who are resistant to treatments with immune checkpoint inhibitors. The therapy involves isolation of T-cells from the own tumour of the patient and further expanding them through ex vivo methods and reinfusing them back into the patient after following the specific regimens and support procedures[22]. Although there are no approved tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapies for CRC, they are being extensively studied in clinical settings.

3.3 CAR-NK Cell Therapy

Chimeric antigen receptor-natural killer (CAR-NK) cell therapy shows a promising frontier in cancer immunotherapy and simultaneously shows a potentially better alternative to CAR-T therapy in terms of both safety and applicability. These genetically engineered CAR-NK cells are used to express the specific receptors that can target the tumour antigens while enhancing their ability to recognise and destroy cancer cells. Due to the usage of NK cells, prior sensitisation is not required, and the risk of graft-versus-host disease is also lowered, which enhances the efficiency of the therapy. Although this therapy has shown great success for haematological malignancies, some challenges are faced when it’s used in the case of solid tumours[23]. CAR-NK cell therapy has demonstrated significant promise for the treatment of CRC in clinical studies[24,25]. Ongoing studies are focused on the optimization of the CAR design as well as overcoming the barriers and improving the efficiency of the therapy[23].

3.4 mAbs, bAbs-mediated Therapy

Therapeutic mAbs and bispecific antibodies (bsAbs) are among the standard treatments used for various types of cancer especially haematological cancers. The mAbs induce cell lysis in the cancer cell by activation of the Fcγ receptors in the innate immune cells. It also helps to opsonise the target cells and trigger classical complement pathways and lead to various crucial immunological reactions[26]. mAbs, including naked mAbs such as cetuximab and bevacizumab, are mainly used in the mainstay treatment for CRC. Cetuximab works by targeting EGFR and has been indicated for metastatic CRC, but bevacizumab inhibits VEGF, thereby limiting tumour angiogenesis[27,28]. Recently developed bsAbs that can interact with multiple epitopes have great potential, especially when administered in combination with anti-PD-1 therapies.

3.5 Oncolytic Viruses

Oncolytic viruses have been shown to be a novel and promising therapeutic option for patients who are resistant to conventional therapies. These genetically modified or natural oncolytic viruses can be used tumour multifaceted destroyal by lysing only the tumour cells directly and by making the anti-tumour immunity more potent by successfully activating the inflammatory response in the tumour microenvironment[29]. Oncolytic viruses, which modified herpes simplex virus and JX-594 can selectively infect and kill cancer cells making them an effective treatment method, but due to limitations such as limited penetration and short persistence of the oncolytic virus on the tumour and other anti-viral mechanisms that occur in the host’s body as a result of the oncolytic vaccine, they have yet to be approved by the FDA for CRC. Cancer vaccines are another approach that attempts to teach the immune system about the identification of cancerous cells. Further research is focused on addressing and overcoming the current challenges as well as the exploring the potential of combinational strategies such as CAR-NK cell therapy and ICB therapy which might help to enhance the therapeutic efficacy[29].

3.6 Peptide, Viral Vector Vaccines and Whole Tumour Vaccines

Peptide vaccines mainly involve the selection of tumour-associated antigens (TAAs) and tumour-specific antigens (TSAs) to stimulate the antigen-presenting cells, which leads to CD8+ T cell activation through MHC-I presentation. This helps in the process of active immunotherapy through which a targeted immune response can be made, which can help with tumour regression[30]. Viral vector-based vaccines, on the other hand, use viruses to deliver tumour antigens that help to elicit a strong humoral and cellular immune response. Similarly, whole tumour vaccines involve the injection of genetically modified or intact tumour lysates or cells with distinct adjuvants. These help to trigger the host's inflammatory and antitumor responses early, which help to control tumour growth[31]. Concerning CRC, Peptide and viral vector vaccines targeting specific antigens have shown promise in inducing an immune response, but have failed to show significant clinical practice, while whole-tumour vaccines have shown variable results.

3.7 ILs-mediated Therapy

By leveraging the natural regulatory roles of interleukins (ILs) in the area of immune cell activation, development and survival, IL-mediated therapy has emerged as a significant component in the modulation of immune responses in cancer immunotherapy[32]. These ILs produced by leukocytes have multiple functions in CRC. While IL-11 and IL-6 promote tumor growth, IL-2 and IL-12 provoke a very potent immune response. Its purpose is to suppress IL-11 and IL-6, which stimulate tumor growth, but utilize IL-2 and IL-12. The potential of other ILs, including IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-33, to improve anti-tumor action has also been investigated, especially in combination therapy for the treatment of CRC. Although there seem to be some challenges, such as systemic toxicity or short half-life, advancements and research are ongoing for the engineering and development of IL derivatives and the required delivery systems, which help to improve the efficacy of the therapy without compromising the safety[32].

3.8 IFNs Mediated Therapy

Interferons (IFNs) are a potent class of cytokines that have a significant immunomodulatory and anti-tumour potential. Specifically, type I and type II IFNs have been shown to have a significant effect on the immune cells and play an important role in the tumour mechanisms. Clinically, Type III IFNs have been shown to have fewer side effects when compared to treatment with Type I IFNs. but mainly among the IFNs that show anti-tumour actions, IFN-γ is a major contributor. IFNs were among the first approved treatments for various advanced malignancies, and despite their efficiency and effectiveness, there are still challenges with the stability and targeted delivery, along with the complexity of the dosing, side effects and hurdles in the process of manufacturing. Therefore, further research is targeted towards precision oncology approaches[33]. Especially in the case of the course of CRC, which is directly associated with its dysregulation. Other targeted agents in combination with IFN-γ and nivolumab are under investigation in clinical trials for MSI-H CRC to ensure the safety and efficacy of the treatment.

3.9 Immunomodulatory Drugs

Immunomodulatory drugs are among notable anticancer agents which help in the treatment of various haematological malignancies, especially multiple myeloma (MM). Although these drugs have been approved for cancer treatment for over a decade, recent research along with the supporting clinical data, shows their immense potential to improve the efficacy of the T cells and NK cell based targeted treatments, which further signifies the potential of these drugs as promising agents in the field of cancer immunotherapy[34]. Immunomodulatory drugs, such as thalidomide, especially when combined with other agents for cytotoxic therapy, augment anti-tumor effects through modification of immunologic function. Targeting immunosuppressive cells, including Tregs and MDSCs, should convert "cold" cancers into "hot" cancers that could respond better to immunotherapy. Additionally, maraviroc, a CCR5 inhibitor, has shown encouraging results in the treatment of metastatic CRC[17].

These approaches show how much progress immunotherapy has made in treating CRC (Table 1)[35-41], but much more has to be done to optimise and broaden its use for all patient subgroups[17].

Table 1. Comparative Table of Current Immunotherapeutic Treatments for CRC[35-41]

No. |

Treatment Type |

Mechanism of Action |

Clinical Status |

Advantages |

Limitations |

1 |

ICB therapy |

Blocks the inhibitory receptors like PD-1, CTLA-4 on T cells, which helps to enhance the anti-tumour immune response |

Approved for MSI-H/dMMR CRC, but ongoing trials for MSS CRC |

· Potential for long-term remission · Durable responses in selected patients |

· Limited efficacy in cases with MSS CRC, · Possibility of adverse immune responses · High cost |

2 |

TILs therapy |

Ex vivo-based expansion of the host’s TILs, along with reinfusion of them back into the host to target the TSAs |

Under clinical investigation for CRC |

· Highly personalised treatment is possible · Potential for targeting neoantigens |

· Limited effectiveness with immunologically cold tumours · Risk of toxicity due to the regimens involved |

3 |

CAR-NK cells therapy |

Engineered CAR-NK cells that use the innate and antigen-specific mechanisms and response to recognise and kill the tumour cells |

Early phase clinical trials are going on for all the solid tumours including CRC |

· Off-the-shelf potential · Reduced risk of graft-versus-host disease and cytokine release syndrome |

· Reduced efficacy in case of immunosuppressive TME · Complexity in the manufacturing · Limited persistence |

4 |

mAbs, bAbs-mediated therapy |

mAbs help to bind to the tumour antigens by which the immune cytotoxicity is mediated, and bAbs function by linking the immune cells with the targeted tumour cells |

Several mAbs have been clinically approved for CRC, e.g. cetuximab, but bAbs are still in development |

· The efficacy of the treatment has been clinically validated · Targeted mechanism is shown |

· Due to the tumour antigen heterogeneity, the efficiency of the treatment is limited · Potential for immune escape · Possibility of adverse reactions |

5 |

Oncolytic virus |

Selective viral infection of the tumour cells is done, which causes its lysis and also helps to provide immune activation against the antigens released |

It is still under investigation for CRC but has been approved for some other cancers like melanoma |

· Helps to combine direct lysis of the tumour along with systemic immune stimulation |

· Possibility of neutralisation of efficacy due to the host anti-viral immunity mechanisms · Limited delivery efficiency |

6 |

peptide, viral vector vaccines and whole tumour vaccines |

Present TAAs and TSAs to stimulate the adaptive and innate immune system responses and mechanisms |

Phase I/II clinical trials are going on for CRC |

· Potential of long-term immunity · Specificity is high |

· Weak immunogenicity · Variability of tumour antigen expression · MHC restriction is seen |

7 |

ILs-mediated therapy |

Utilisation of ILs to stimulate the proliferation and cytotoxic activity of the lymphocytes and aid in the anti-tumour activities |

Approved for some other cancers, but is still under evaluation for CRC |

· Allows for broad activation of the effector cells · Helps to enhance other cancer immunotherapies |

· Dose-limiting toxicities are observed · Possibility of systemic side effects · Might have transient effects |

8 |

IFN-mediated therapy |

Utilisation of the IFNs like IFN-α and IFN-γ to enhance the antigen presentation, cytotoxic immunity, as well as to enhance the anti-cancer and immunomodulatory properties |

It is approved but has limited use in the case of CRC. |

· Has both immunostimulatory and anti-proliferative effects · Helps to make other immunotherapies more efficient |

· Might cause flu-like symptoms · Possibility of haematological toxicity · Only marginal efficacy in the case of CRC |

9 |

Immunomodulatory drugs |

Modulate the immune pathways to enhance the antitumour immunity and cytotoxic effects, and can also be used in combination with other therapies to enhance efficacy |

It is still under investigation for CRC |

· Has multi-modal effects · Some of the agents are orally bioavailable |

· Might have systemic side effects · Has complex immunodynamics |

4 EMERGING CHALLENGES AND RESISTANCE MECHANISMS IN IMMUNOTHERAPY FOR CRC

Although several immunotherapy approaches, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors and combinations, have been encouraging in CRC, their efficacy still largely holds up in MSI-H or mismatch repair-deficient tumours. Most CRCs, which are MSS, on the other hand, still do not respond due to a number of multifactorial reasons. Primary resistance to MSS-CRC is fueled by low tumour mutational burden (TMB), decreased neoantigen expression, and absence of cytotoxic T cell infiltration, creating immunologically "cold" tumours poorly perceived by the immune system[42,43]. Dense stromal structure, dysregulated vasculature, and an immunosuppressive tumour microenvironment that is rich in regulatory T cells, MDSCs, and tumour-associated macrophages further limit immune activation[44]. Adaptive resistance mechanisms comprise immune editing, antigen loss variants, and upregulation of alternative inhibitory checkpoints like TIM-3 and LAG-3[45,46]. Tumour cells also escape immune surveillance through downregulation of elements of the antigen presentation machinery like MHC-I and β2-microglobulin[47]. The gut microbiota now has a central role as a modulator of immune response, and individual microbial species either promote or suppress immunotherapeutic efficacy[48,49]. In addition, genetic mutations such as POLE/POLD1 mutations will increase immunogenicity, whereas epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation, will suppress immune-relevant genes[50,51]. Such multifactorial resistance pathways are now guiding the future direction of next-generation immunotherapies, including rational combination regimens, epigenetic medications, microbiome-directed approaches, and biomarker-stratified precision strategies, all for expanding the reach and endurance of immune-mediated treatments of CRC[52,53].

5 FUTURE DIRECTIONS AND NOVEL STRATEGIES

With the limitations of existing immunotherapy platforms, future research in CRC is more focused on maximising the personalisation of treatment, reducing immune resistance, and incorporating predictive measures for patient stratification. One of the main frontiers is adopting multi-omic profiling involving genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics to determine patient-specific immune signatures that can inform individualised treatment choices and predict resistance[54,55]. Liquid biopsies and circulating tumour DNA are also under investigation to track immune response and tumour evolution dynamically, allowing for real-time treatment adjustments[55]. Microbiome interventions, beyond correlation studies, are heading toward engineered microbial consortia and precision microbiota editing to stimulate immunogenicity in resistant CRC phenotypes[47,56]. Strategies aimed at stromal remodelling and immune exclusion zones, including CAF reprogramming or ECM-degrading enzymes, are being explored to enhance immune cell infiltration in "cold" tumours[57,58]. Moreover, machine learning and artificial intelligence models are being designed to forecast immunotherapy responses and tailor combination regimens according to complex biomarker inputs[58]. Last, research is in progress to craft next-generation immunomodulatory drugs that balance immune activation with avoiding autoimmunity, such as selective agonists/antagonists of co-stimulatory or co-inhibitory pathways yet to be leveraged clinically[59,60]. Collectively, these new technologies portend a move toward intensely adaptive, biomarker-based, systems-level strategies that will potentially deliver sustainable immunotherapy responses to an expanded CRC patient population, particularly those with MSS tumours.

6 CONCLUSION

Immunotherapy has significantly altered the treatment landscape for CRC, especially in patients with dMMR or MSI-H tumours. However, the majority of CRC cases, like MSS tumours, remain largely resistant to current immune-based therapies due to an immunologically "cold" microenvironment and low immune infiltration. Overcoming both primary resistance and acquired immune escape remains a significant challenge in increasing the use of immunotherapies in CRC. Overcoming both primary resistance and acquired immune escape remains a major challenge in expanding the use of immunotherapies in CRC. Recent advances, such as the identification of predictive biomarkers like TMB, POLE mutations, and immune cell composition, provide critical insights for more accurate patient stratification. Importantly, tumour heterogeneity, both between and within patients, highlights the need for personalised therapeutic approaches.

Moving forward, a paradigm shift towards biomarker-driven, tumour-specific immunomodulation is required. Integrating single-cell and spatial transcriptomics, artificial intelligence, and systems immunology can help identify new immune escape mechanisms and therapeutic vulnerabilities. Furthermore, the development of next-generation immune checkpoints, personalised neoantigen vaccines, and rational immunotherapeutic combinations holds promise for broadening long-term responses across all CRC subtypes. Finally, transforming immunotherapy from a niche treatment to a cornerstone of CRC care will necessitate a comprehensive strategy that integrates molecular understanding, technological innovation, and clinical translation, providing new hope for patients with advanced or refractory disease.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this review as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Copyright Permissions

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Innovation Forever Publishing Group Limited. This open-access article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Author Contribution

Kaunain SF was responsible for concept, designing and writing; Pandurangan AK was responsible for concept, processing, analysis, interpretation, and reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript and approved the final version.

Abbreviation List

ACT, Adoptive cell therapy

CAR-NK, Chimeric antigen receptor-natural killer cell

bsAbs, Bispecific antibodies

CRC, Colorectal cancer

ICB, Immune checkpoint blockade

IFNs, Interferons

ILs, Interleukins

mAbs, Monoclonal antibodies

MDSCs, Myeloid-derived suppressor cells

MSS, Microsatellite stable

TAAs, Tumour-associated antigens

TIL, Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte

TMB, Tumour mutational burden

TSAs, Tumour-specific antigens

[1] Li W, Liu J, Lan Y et al. Development and validation of survival prediction tools in early and late onset colorectal cancer patients. Sci Rep, 2025; 15: 12864.[DOI]

[2] Oon CE, Anbazhagan P, Tan CT. Therapeutic potential of targeting ubiquitin-specific proteases in colorectal cancer. Drug Discov Today, 2025; 30: 104356.[DOI]

[3] Duan B, Zhao Y, Bai J et al. Colorectal Cancer: An Overview. In: Morgado-Diaz JA, editor. Gastrointestinal Cancers. Brisbane (AU): Exon Publications. 2022.[DOI]

[4] Wong CC, Yu J. Gut microbiota in colorectal cancer development and therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 2023; 20: 429-452.[DOI]

[5] Spaander MCW, Zauber AG, Syngal S et al. Young-onset colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2023; 9: 21.[DOI]

[6] Zygulska AL, Pierzchalski P. Novel Diagnostic Biomarkers in Colorectal Cancer. Int J Mol Sci, 2022; 23: 852.[DOI]

[7] Tong Q, Wu Z. Curcumin inhibits colon cancer malignant progression and promotes T cell killing by regulating miR‐206 expression. Clin Anat, 2024; 37: 2-11.[DOI]

[8] Zheng A, Li H, Wang X et al. Anticancer effect of a curcumin derivative B63: ROS production and mitochondrial dysfunction. Curr Cancer Drug Tar, 2014; 14: 156-166.[DOI]

[9] Mohebali N, Pandurangan AK, Mustafa MR et al. Vernodalin induces apoptosis through the activation of ROS/JNK pathway in human colon cancer cells. J Biochem Mol Toxic, 2020; 34: e22587.[DOI]

[10] Li D, Wang G, Jin G et al. Resveratrol suppresses colon cancer growth by targeting the AKT/STAT3 signaling pathway. Int J Mol Med, 2019; 43: 630-640.[DOI]

[11] Ding F, Yang S. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits proliferation and triggers apoptosis in colon cancer via the hedgehog/phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathways. Can J Physiol Pharm, 2021; 99: 910-920.[DOI]

[12] Hu H, Zhang M. PD-1 involvement in CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in patients with colonic-derived peritoneal adenocarcinoma. Braz J Med Biol Res, 2025; 58: e14467.[DOI]

[13] Xu J, Zhou H, Liu Z et al. PDT-regulated immune gene prognostic model reveals tumor microenvironment in colorectal cancer liver metastases. Sci Rep, 2025; 15: 13129.[DOI]

[14] Patel P, Nessel TA, Zito PM. Immunotherapy. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing: Florida, USA, 2024.

[15] Liu C, Yang M, Zhang D et al. Clinical cancer immunotherapy: Current progress and prospects. Front Immunol, 2022; 13: 961805.[DOI]

[16] Butterfield LH, Najjar YG. Immunotherapy combination approaches: mechanisms, biomarkers and clinical observations. Nat Rev Immunol, 2024; 24: 399-416.[DOI]

[17] Weng J, Li S, Zhu Z et al. Exploring immunotherapy in colorectal cancer. J Hematol Oncol, 2022; 15: 95.[DOI]

[18] Carlsen L, Huntington KE, El-Deiry WS. Immunotherapy for colorectal cancer: Mechanisms and predictive biomarkers. Cancers, 2022; 14: 1028.[DOI]

[19] Rastin F, Javid H, Oryani MA et al. Immunotherapy for colorectal cancer: rational strategies and novel therapeutic progress. Int Immunopharmacol, 2024, 126: 111055.[DOI]

[20] Sun Q, Hong Z, Zhang C et al. Immune checkpoint therapy for solid tumours: clinical dilemmas and future trends. Signal Transduct Tar, 2023; 8: 320.[DOI]

[21] Liu G, Zhang Y, Cao Z et al. Targeting KIF18A triggers antitumor immunity and enhances efficiency of PD-1 blockade in colorectal cancer with chromosomal instability phenotype. Cell Death Discov, 2025; 11: 130.[DOI]

[22] Betof Warner A, Corrie PG, Hamid O. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte Therapy in Melanoma: Facts to the Future. Clin Cancer Res, 2023; 29: 1835-1854.[DOI]

[23] Wang W, Liu Y, He Z et al. Breakthrough of solid tumor treatment: CAR-NK immunotherapy. Cell Death Discov, 2024; 10: 40.[DOI]

[24] Tan Z, Tian L, Luo Y et al. Preventing postsurgical colorectal cancer relapse: A hemostatic hydrogel loaded with METTL3 inhibitor for CAR-NK cell therapy. Bioact Mater, 2025; 44: 236-255.[DOI]

[25] Torchiaro E, Cortese M, Petti C et al. Repurposing anti-mesothelin CAR-NK immunotherapy against colorectal cancer. J Transl Med, 2024; 22: 1-13.[DOI]

[26] Collier-Bain HD, Brown FF, Causer AJ et al. Harnessing the immunomodulatory effects of exercise to enhance the efficacy of monoclonal antibody therapies against B-cell haematological cancers: a narrative review. Front Oncol, 2023; 13: 1244090.[DOI]

[27] Cortese M, Torchiaro E, D’Andrea A et al. Preclinical efficacy of a HER2 synNotch/CEA-CAR combinatorial immunotherapy against colorectal cancer with HER2 amplification. Mol Ther, 2024; 32: 2741-2761.[DOI]

[28] Maia A, Tarannum M, Lérias JR et al. Building a Better Defense: Expanding and Improving Natural Killer Cells for Adoptive Cell Therapy. Cells, 2024, 13: 451.[DOI]

[29] Ma R, Li Z, Chiocca EA et al. The emerging field of oncolytic virus-based cancer immunotherapy. Trends Cancer, 2023; 9: 122-139.[DOI]

[30] Buonaguro L, Tagliamonte M. Peptide-based vaccine for cancer therapies. Front Immunol, 2023; 14: 1210044.[DOI]

[31] Pérez-Baños A, Gleisner MA, Flores I et al. Whole tumour cell-based vaccines: tuning the instruments to orchestrate an optimal antitumour immune response. Brit J Cancer, 2023; 129: 572-585.[DOI]

[32] Vahidi S, Touchaei AZ, Samadani AA. IL-15 as a key regulator in NK cell-mediated immunotherapy for cancer: from bench to bedside. Int Immunopharmacol, 2024; 133: 112156.[DOI]

[33] Lim J, Lee HK. Engineering interferons for cancer immunotherapy. Biomed Pharmacother, 2024; 179: 117426.[DOI]

[34] Colley A, Brauns T, Sluder AE et al. Immunomodulatory drugs: a promising clinical ally for cancer immunotherapy. Trends Mol Med, 2024; 30: 765-780.[DOI]

[35] Liu C, Yang M, Zhang D et al. Clinical cancer immunotherapy: Current progress and prospects. Front Immunol, 2022; 13: 961805.[DOI]

[36] Mishra AK, Ali A, Dutta S et al. Emerging Trends in Immunotherapy for Cancer. Diseases, 2022; 10: 60.[DOI]

[37] Rui R, Zhou L, He S. Cancer immunotherapies: advances and bottlenecks. Front Immunol, 2023; 14: 1212476.[DOI]

[38] Carlsen L, Huntington KE, El-Deiry WS. Immunotherapy for Colorectal Cancer: Mechanisms and Predictive Biomarkers. Cancers, 2022; 14: 1028.[DOI]

[39] Zhou Y, Wei Y, Tian X, et al. Cancer vaccines: current status and future directions. J Hematol Oncol, 2025; 18: 18.[DOI]

[40] Luo D, Liu Y, Lu Z et al. Targeted therapy and immunotherapy for gastric cancer: rational strategies, novel advancements, challenges, and future perspectives. Mol Med, 2025; 31: 52.[DOI]

[41] Xiao M, Tang Q, Zeng S et al. Emerging biomaterials for tumor immunotherapy. Biomater Res, 2023; 27: 47.[DOI]

[42] Ganesh K, Stadler ZK, Cercek A et al. Immunotherapy in colorectal cancer: rationale, challenges and potential. Nat Rev Gastro Hepat, 2019; 16: 361-375.[DOI]

[43] Gurjao C, Liu D, Hofree M et al. Intrinsic resistance to immune checkpoint blockade in a mismatch repair–deficient colorectal cancer. Cancer Immunol Res, 2019; 7: 1230-1236.[DOI]

[44] Angell HK, Bruni D, Barrett JC et al. The immunoscore: colon cancer and beyond. Clin Cancer Res, 2020; 26: 332-339.[DOI]

[45] Limagne E, Richard C, Thibaudin M et al. Tim-3 blockade enhances tumor response to anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 in MSS colorectal cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2021; 9: e001930.

[46] Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science, 2017; 357: 409-413.[DOI]

[47] Gurjao C, Liu D, Hofree M et al. Intrinsic resistance to immune checkpoint blockade in a mismatch repair–deficient colorectal cancer. Cancer Immunol Res, 2019; 7: 1230-1236.[DOI]

[48] Gopalakrishnan V, Spencer CN, Nezi L et al. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti–PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science, 2018; 359: 97-103.[DOI]

[49] Wong SH, Kwong TNY, Chow TC et al. Quantitation of faecal Fusobacterium improves faecal immunochemical test in detecting advanced colorectal neoplasia. Gut, 2017; 66: 1441-1448.[DOI]

[50] Germano G, Lamba S, Rospo G et al. Inactivation of DNA repair triggers neoantigen generation and impairs tumour growth. Nature, 2017; 552: 116-120.[DOI]

[51] Dunn J, Rao S. Epigenetics and immunotherapy: the current state of play. Mol Immunol, 2017; 87: 227-239.[DOI]

[52] Topalian SL, Taube JM, Pardoll DM. Neoadjuvant checkpoint blockade for cancer immunotherapy. Science, 2020; 367: eaax0182.[DOI]

[53] Sharma P, Hu-Lieskovan S, Wargo JA et al. Primary, Adaptive, and Acquired Resistance to Cancer Immunotherapy. Cell, 2017; 168: 707-723.[DOI]

[54] Zhang Y, Zhang Z. The history and advances in cancer immunotherapy: understanding the characteristics of tumor-infiltrating immune cells and their therapeutic implications. Cell Mol Immunol, 2020; 17: 807-821.[DOI]

[55] Cristescu R, Mogg R, Ayers M et al. Pan-tumor genomic biomarkers for PD-1 checkpoint blockade–based immunotherapy. Science, 2018; 362: eaar3593.[DOI]

[56] Topper MJ, Vaz M, Chiappinelli KB et al. Epigenetic Therapy Ties MYC Depletion to Reversing Immune Evasion and Treating Lung Cancer. Cell, 2017; 171: 1284-1300.[DOI]

[57] Fukuoka S, Hara H, Takahashi N et al. Regorafenib Plus Nivolumab in Patients With Advanced Gastric or Colorectal Cancer: An Open-Label, Dose-Escalation, and Dose-Expansion Phase Ib Trial (REGONIVO, EPOC1603). J Clin Oncol, 2020; 38: 2053-2061.[DOI]

[58] Zhu YJ, Li X, Chen TT et al. Personalised neoantigen‐based therapy in colorectal cancer. Clin Transl Med, 2023; 13: e1461.[DOI]

[59] Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Adoptive cell transfer as personalized immunotherapy for human cancer. Science, 2015; 348: 62-68.[DOI]

[60] Tauriello DVF, Palomo-Ponce S, Stork D et al. TGFβ drives immune evasion in genetically reconstituted colon cancer metastasis. Nature, 2018; 554: 538-543.[DOI]

Copyright ©

Copyright ©